About the author

Tony Weis is an associate professor of geography at the University of Western Ontario, with research broadly located in the field of political ecology. He is the author of The Global Food Economy: The Battle for the Future of Farming (Zed Books, 2007), and numerous articles and book chapters on environmental and development issues regarding agriculture.

THE ECOLOGICAL HOOFPRINT

THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF INDUSTRIAL LIVESTOCK

Tony Weis

Zed Books

LONDON | NEW YORK

The Ecological Hoofprint: the global burden of industrial livestock was first published in 2013 by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London N1 9JF, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

This ebook edition was first published in 2013

www.zedbooks.co.uk

Copyright Tony Weis 2013

The right of Tony Weis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Set in Monotype Plantin and FFKievit by Ewan Smith, London NW5

Index:

Cover design: www.alice-marwick.co.uk

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available

ISBN 978 1 78032 099 1

FIGURES AND BOXES

Figures

Boxes

To Jenn, Marley, and Kevay, for your abiding love and support

INTRODUCTION: MEATIFICATION AND WHY IT MATTERS

The vector of meatification

On a global scale, human diets are in the midst of a great transformation, which is wrapped up in the radical narrowing of agricultural production. One of the most fundamental aspects of this is the rising consumption of animal flesh and derivatives, principally from pigs, poultry, and cattle. The average person today eats almost twice as much meat as did the average person only two generations ago, along with many more eggs, in a world with more than twice as many people now as then. In 1961, just over three billion people ate an average of 23 kg of meat and 5 kg of eggs a year. By 2011, 7 billion people ate 43 kg of meat and 10 kg of eggs a year. This translates to a quadrupling of world meat production in a mere half-century, from 71 to 297 million tonnes, and an even greater rise in world egg production, from 15 to 69 million tonnes. World milk production more than doubled, roughly in line with human population growth, with the average person consuming 104 kg in 2010.

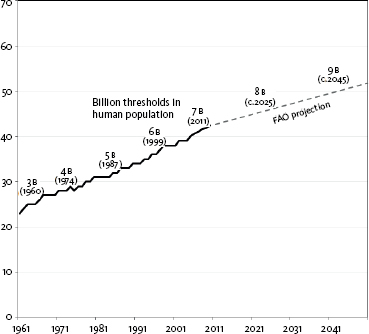

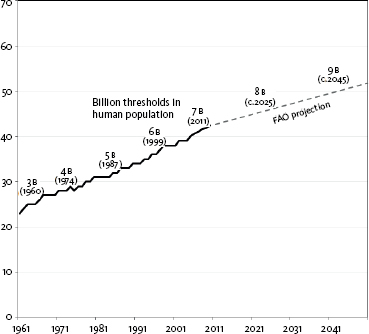

Industrial livestock production is the driving force behind the rapid growth in meat and egg consumption, in what are variously referred to as Intensive or Industrial Livestock Operations (ILOs), Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), or factory farms and feedlots. This transformation permeates everyday life in a way that is both intimate, in the bodily encounter with food, and overwhelmingly unconscious. Rapid growth is expected to continue in the coming decades. By 2050, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations projects that global meat production will rise to 52 kg per person in a world with 9.3 billion people, which amounts to 484 million tonnes (see

This broad picture contains huge disparities. Although increasing per capita meat consumption is occurring almost everywhere, people in rich countries consume vastly more meat than do most people in

0.1 Global per capita meat consumption (kg/person) ( sources : )

When the lens moves from volume increases to individual animals consumed, the pace of growth becomes even more staggering. In a mere half-century, from 1961 to 2010, the global population of slaughtered animals leapt from roughly 8 to 64 billion, which will double again to 120 billion by 2050 if current rates of growth continue. The stunning rise in the number of individual animals slaughtered reflects the

This general trajectory has been termed the livestock revolution in one frequently cited report. Such transitional narratives have a naturalizing effect, because if different parts of the world are seen to be located at different stages along the same course, with all moving towards an improved condition, it can serve to legitimize the course itself and make large inequalities seem less troubling.

Layered onto this is an insistence by prominent actors that further yield enhancement is the key to solving present and future world food problems, which is sometimes described in terms of closing global yield gaps, especially in poor under-yielding countries. Yield-centric narratives are also linked to an insistence that world food production must double by mid-century if it is to meet future demand. But the scale of chronic hunger (nearly one billion people) and malnourishment today, and expected population growth (more than two billion), still do not come close to adding up to a doubling scenario, which must also be understood to contain an uncritical expectation that meat consumption will continue climbing rapidly. These assumptions there will be more meat consumed, total food production must double are influential starting points for contemporary debates about agricultural futures. They are also extremely dubious and dangerous ones.

First, this seeks to call attention to the pace and scale of change. For most of the 10,000-year history of agriculture, meat, eggs, and dairy were consumed periodically and in relatively small volumes, and it was not until the industrialization of livestock production that they began to shift from the periphery to the center of human diets on a world scale. Secondly, the notion of meatification seeks to dispel the imagery of a course that is natural, inevitable, or benign. Great volumes of industrial grains and oilseeds are being inefficiently cycled through soaring populations of concentrated animals, with much usable nutrition lost in the metabolic processes of animals before getting converted to meat, eggs, and dairy. The ensuing production is then highly skewed toward wealthier consumers when, as indicated, one in seven people on earth are hungry or malnourished and many more in varying states of food insecurity. Globally, livestock consume around one third of all grains and a much larger share of all oilseeds, and flows of crops through livestock are much higher in industrialized countries than in poor ones. The aim of this book is to provide a new way of understanding the momentousness of this trajectory, its multidimensional impacts, and the urgency of confronting it.

Rising attention

This aim should not imply that this book is stepping into a vacuum. On the contrary, there has been a great deal of important work examining the nature and impacts of industrial livestock. Three of the key foundations were Ruth Harrisons pioneering assessment of the early stages of industrializing livestock, Frances Moore Lapps seminal argument about the global injustice of cycling rising volumes of grain through livestock in a world of widespread hunger, and Peter Singers moral-philosophical case against speciesism, which included a searing indictment of the treatment of animals in factory farms. which can be broadly seen to focus on:

human health (e.g. chronic diseases, food safety risks);

Next page