NATURES

DESIGN

exploring the mysteries of the natural world

Richard Thompson

DEDICATION

This book is for my children Julian, Sarah, Adrian, Katherine and Hannah with much love. And for Deborah Carter, who changed everything.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book owes its origins to many conversations with Colin Walker children's author, educationalist and friend in Wellington. Thanks to the reference librarians at the Wellington Clinical School of Medicine for their diligent searches for often obscure material. A large thank you to Helen de Villiers whose editorial skills created order from chaos. And many thanks to Linda Crerar who typed the original manuscript.

Struik Nature

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Cornelis Struik House

80 McKenzie Street

Cape Town

8001 South Africa

Company Reg. No 1966/003153/07

Visit us at www.randomstruik.co.za

First published in 2008

Copyright in published edition, 2008: Struik Nature

Copyright in text, 2008: Richard Thompson

Copyright in illustrations, 2008: Struik Nature

Publishing manager: Pippa Parker

Editor: Helen de Villiers

Designer: Janice Evans

Illustrator: Lucy Owen

Proofreader: Jane Smith

Indexer: Cora Ovens

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright owner(s).

ISBN 978 1 77007 724 9 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 77007 967 0 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77007 968 7 (Pdf)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

EMERGING FROM THE FORESTS

the story of grass

The chickens have, in the absence of their staple diet of grain, taken to the woods in search of alternatives.

A world without grass

Ours is a world of grass think of our suburban lawns, our sports fields and inner city parks, our countryside with patchwork quilts of welltended fields and windswept uplands dotted with sheep. On a much larger scale, give some thought to the great natural grasslands of the world the prairies and pampas of the Americas, the steppes of Eurasia, the plains and savannahs of Africa and the Canterbury plains of New Zealand. Consider, too, that all the major cereal crops are members of the grass family, a list including wheat, barley, rye, oats, sorghum, maize, sugar cane and even rice.

With global temperatures predicted to increase by a matter of three to five degrees centigrade in this century, our grandchildren may have to confront a world where drought and heat have shrivelled the grasslands to scrub and desert. In this brave new world, a farmer draws the curtains to greet a new day. The view from his window is no longer one of fields full of lush meadow grass or crops bending in the wind, but the bleak aspect of barren earth spotted with weeds and other invaders. Of course, he may have planted acres of root vegetables and the fare of market gardens but, if he has not, then the land will slowly but surely return to the forests that flourished here long ago. In the farmyard he will find silence the chickens, which in days past fussed and squabbled around his feet have, in the absence of their staple diet of grain, taken to the woods in search of alternatives. They are unlikely to survive the first winter. In days gone by, the farmer was able to send grain to the miller to be ground into flour, but the mill wheels are now immobile there is to be no more bread. The barn will soon house a dusty museum of rusting and obsolete machinery. And there will be no more bales of hay prudently laid down at harvest time to feed the stock over a harsh winter; not that this matters particularly, because there is no longer any stock to feed. All the animals that depended on grass as a primary or sole food source are now dead: there are no horses, no cattle, no sheep and no goats. The only domesticated or semi-domesticated animals likely to survive are the pig and the forest deer.

Stretching in a broad sweep from Canada to Kansas, the great heartland of America is now a dust bowl, a place where only hardy plants such as the inedible sage and tumbleweed can survive and where trees are limited to the banks of permanent water courses. In the wake of these events the dairy industry is in ruins and a similar fate has befallen the meat industry and the woollen mills. The economies of the Americas and Europe are in tatters. Farmers in Asia, now faced with vistas of empty rice paddies, will dread the consequences of losing a crop that feeds over half the worlds population. African farmers, too, having lost their maize, cattle and goats, which form the dietary cornerstone of a whole continent, will face starvation.

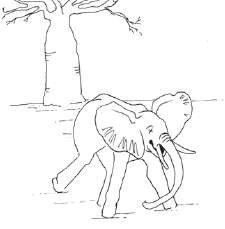

In the aftermath of such a global catastrophe, the fate of the worlds wilder places would be sealed. The plains of Africa would be silent, the migrating herds consigned to memory no flicker of tension rippling along the flank of a zebra before it explodes into full gallop, no growl from a tawny shape hidden in the undergrowth and no telltale dust cloud to give away the distant passage of a herd of wildebeest or buffalo. No sign, in fact, of any grazing antelope or gazelle, no trace of zebra, wildebeest, buffalo or hippopotamus. And in their wake would follow the predators that stalk them lion, leopard, cheetah, hyaena and wild dog.

And, on a more personal note, there would be a large question mark hovering over the whole evolution of our own species. Would we even have existed in a world without grass? Ancestral man moved out from the tree line to forage on the grasslands and savannah of Africa, searching for fruits and roots and acquiring, in time, a taste for the flesh of other creatures. Initially hunting in groups to drive large predators from their kills, he gradually developed the necessary weapons and skills to become a hunter in his own right. Later, the necessity of a nomadic existence in the continual search for food gave way to a more stable society when primitive man acquired the ability to domesticate wild animals and to cultivate and harvest the seeds of wild grasses a less risky and more reliable method of food production. But, in the absence of the grasslands, and hence of a readily available four-footed food supply or of seeds to sow, would he have ventured beyond the forest? What would have been the incentive? Confined to forest and woodland by availability of food, natural selection would not have favoured the emergence of a species with a straight spine and with hip joints enabling upright walking, which would have reduced climbing ability. Is it possible that our own evolution would have halted at this point, making no progress beyond that of the modern-day wild primates living on a diet of leaves, fruits, nuts, seeds and small monkeys?