Contents

Guide

Page List

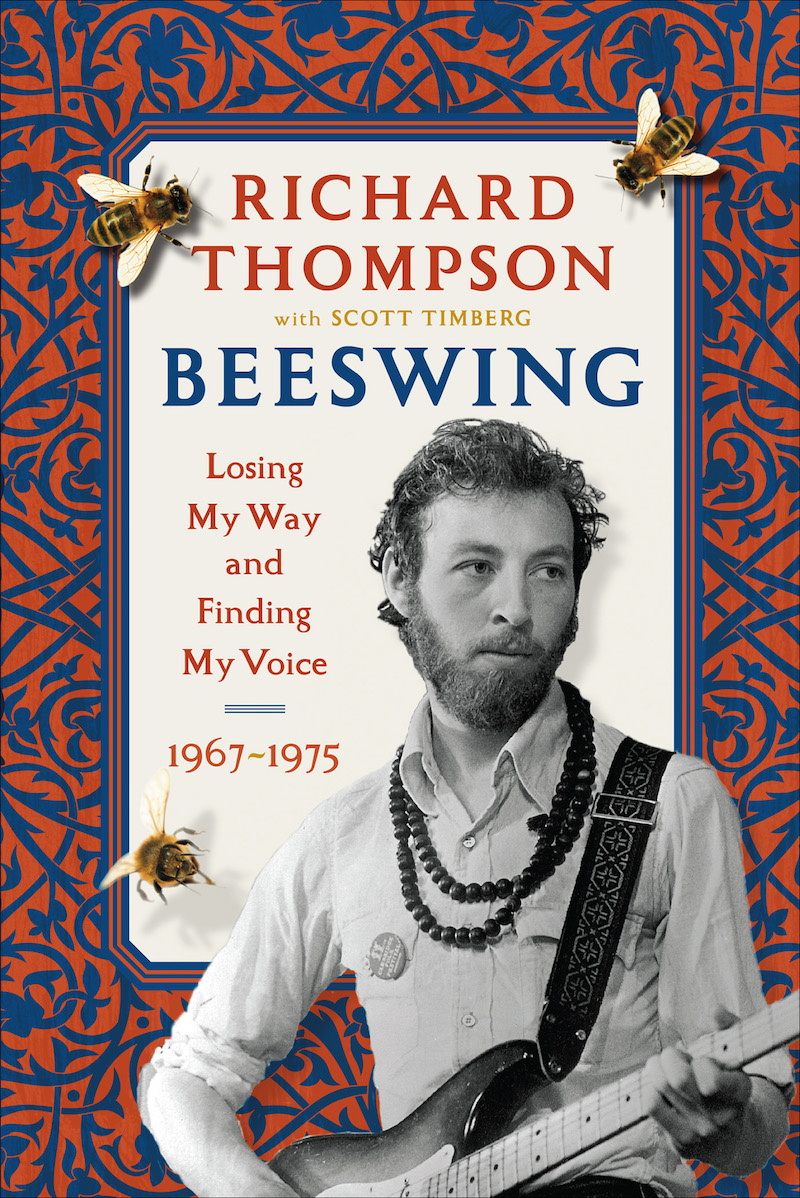

BEESWING

Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 19671975

RICHARD THOMPSON

with scott timberg

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill 2021

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2021 by Richard Thompson. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020051893

eISBN 978-1-64375-170-2

Contents

1

To Jump like Alice

I have nothing to say, I am saying it, and that is poetry as I need it.

John Cage

There is dust, and then there is dust. Its thickest here, in my memory. This remotest room of my mind has been shut up for years, the windows shuttered, the furniture covered with dust sheets. Light hasnt penetrated into some of these corners for years; in some cases it never has. If something is uncomfortable, I shove it in here and forget about it. When was the last time I dared look? I dont want to remember, but now it is time to think back. The arrow is arcing through the air and speeding towards its appointed target.

Then there is the dust of London. When my story begins, in the 1960s, the fog is lifting a little. The choking smogs of my childhood, with visibility down to a yard, have been curtailed, for the sake of public health, by the Clean Air Act of 1956. The dust, dirt and grime of a million coal fires, hundreds of steam trains and massive power stations is receding as they are slowly replaced by cleaner fuelbut I miss it. I miss the sulphurous fog that linked you to the London of Sherlock Holmes and Dickens, that inspired visiting French Impressionists to paint the citys blurred sunrises and sunsets, and that made everything soft and mysterious. It was part of London, and part of being a Londoner. I suppose even poison is something you can grow fond of.

In the spring of 1967 I had just turned eighteen, and there was another kind of dust in my life entirely, so thick you could see it hang in the air, composed of 50 percent chalk, 30 percent boredom and 20 percent dull amusement. The dust of school gets into your lungsmolecules of it are still in there, I swear, clinging to the bronchioles like crabs to a sea wall, even fifty years later. No amount of violent coughing or deep breathing will shift it. It seems to have penetrated my DNA. Maybe thats why I still dream about school, guilty dreams, dreams of unfulfillment, dreams where Im avoiding, running away, non-confronting. On a sunny day, and the sun still shone in black and white in 1967, you could see the dust hanging in the sunbeams like cigarette smoke caught in the projector beam at the local flea pit.

At least I was on the final lap. A few more months, a few more exams, and I would be paroled at last, free after thirteen years of incarceration. I had no stomach for further education, and I had no plan A, B or C. The thought of spending another three years in an institution did not appeal. Hospitals, prisons, schools, insane asylumsin Britain they all seemed to have been designed by the same Victorian sadist, and all shared the same decor: Urine Green and Despair Grey. I went to a good school, William Ellis Grammar, on the edge of Hampstead Heath. The Heath has been described as the lungs of London, a rural enclave a fifteen-minute Tube ride from the center of the city. Sitting on London clay and Bagshot sand, it could never be built upon with reliability, which saved it from the developers. The school supplied a fair number of candidates to Oxford and Cambridge, and provided a fine education for those who could be botheredbut I drifted through it. I only cared about the guitar.

One of my earliest memories, from when I was about three, is of the attic at 23 Ladbroke Crescent. Notting Hill, just west of Central London, was a fairly run-down area in the early fifties, and our street was pockmarked with shrapnel damage from the war. In fact, one end of the street was a bomb site. It was fenced off, of course, but we kids found a way in and played joyfully among the smashed porcelain, knee-scraping rubble and broken artifacts of ruined lives. My familymy father, my mother, my sister Perri and Ilived in a flat in the upper half of the house, a few doors down from my mothers father at number 19. My grandad kept chickens in his back garden, and would often run out into the street with a shovel after a horse and cart had passed by to get the manure for his roses. I remember being taken up to the attic by my parents, presumably so they could keep an eye on me while they looked for something. I had never been in an attic before, so it was a new and thrilling experience. At one point, my father opened a case and pulled out a magical wooden box with strings on it. The box made noises, and you could change them by turning the pegs at the end. My father ran his hand across the strings. It sounded like heaven, and I wanted to hear more, but after a minute or so he put it back in the case, and I never saw it again. Did he sell it soon afterwards? Perhaps he thought it a luxury at a time when money was tight, but its sound stayed with me.

If Dad was not much of a guitarist, he did have plenty of records. In among the albums of show tunes that everyones parents seemed to own, and the Perry Como and the Gilbert and Sullivan, there were jazz recordsFats Waller, Meade Lux Lewis, Duke Ellingtonand among these were lots of guitar 78s. There was the Quintette du Hot Club de France, including the astonishing Django Reinhardt; there was Lonnie Johnson, playing with the Louis Armstrong Hot Seven; and then there was Les Paul, inventing multitrack recording. I remember lying on a sea-green shagpile rug in the living room, with my ear a foot from the radiogram speaker. I must have been all of five years old. Much of the furniture in the room was mid-century modern, G-Plan, but the dark walnut radiogram seemed ancient.

I liked some of my fathers records and disliked others; I seemed to have some sort of critical instinct, even at such a young age. Dad would keep up a running commentary on the music, in his cockney-inflected Scottish accent. Hed talk mostly to himself, reverentially, like a tour guide at the Vatican. Louis Armstrong Hot Fiverecorded in 1926... thats Earl Hines on piano... I saw him in Glasgow in the thirties. Hed always sound authoritative, but I could tell he was reading most of it off the back of the record sleeve. The next thing he put on grabbed me and held my attention. It started with percussion, before slowly sprouting wings and sounding like nothing I had ever heard. The only thing I could compare it to was the music played on radio or TV programs to evoke alien worlds and life forms. Caravan, said my father. Thats a Duke Ellington tune, played by Les Paul on guitar. He did the whole thing himself. I didnt understand what I was hearingI only knew that it sounded like it was from Mars, and that it was fabulous. I didnt know how to ask to hear it again, so I just waited for the next time.

My sister Perri was five years my senior, and when rock and roll hit Britain in 1956, first with Bill Haley and then with Elvis, she was strongly identifying with the baby boomer generation. Even back then, at the tender age of twelve, she pitched her look somewhere between Julie Christie and Brigitte Bardot. I dont remember a time when boys werent hanging aroundand some of them played the guitar and brought over records.