A number of people have been helpful to me in the writing of this book, and I should like to express gratitude to all of them. To one, Charles Sheffield, the book has been dedicated, since without his cooperation and assistance it could never have been written. Others who have generously given me their time include Mrs. James H. Douglas, who provided me with information about her brother and about the Thompson family and also read the manuscript; Mrs. Connie Mangskau and Dr. and Mrs. T.G. Ling, who answered many questions concerning the fateful weekend in the Cameron Highlands; and Dr. and Mrs. Einer Ammundsen, Mrs. Lewis Thompson, Mrs. William R. Bond, Miss Elizabeth Lyons, and Mr. Charles Baskerville, who furnished useful memories of the subject. I should also like to thank Mr. Frank Dyckman and Mrs. Joyce Hartman of Houghton Mifflin Company, the former for suggesting the idea of the book and providing constant encouragement during its writing, the latter for her many wise editorial suggestions.

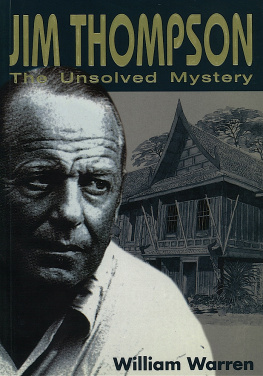

O n Easter Sunday afternoon in 1967, an American businessman from Thailand named James H.W. Thompson disappeared, perhaps while on an innocent stroll, perhaps not, in the jungled mountains of central Malaysia. The circumstances surrounding his disappearance were unusual, to say the least, and Thompson was already the subject of a considerable legend; these two factors combined to assure the case of an extraordinary amount of public attention. A number of people involved in the affair, especially those closest to Thompson, thought the interest would die down in time, but for a variety of reasons this has not happened. In 1997, on the thirtieth anniversary, the British Broadcasting Corporation, the International Herald Tribune, and numerous other media outlets featured prominent stories on the mystery, and theories regarding a possible solution still abound, not only in most of the capitals of Southeast Asia, where Thompson was a familiar figure, but also in American and European circles. The disappearance has, in fact, assumed the proportions of a second Thompson legend, which with its tempting array of possibilities, threatens to obscure the very real and remarkable achievements that were the basis of the first.

Jim Thompson, as he was generally known, was sixty-one years old in 1967. His life had not really taken its distinctive shape, however, until he was in his early forties, at an age when radical changes are difficult to make. Paradoxically, this is a restless time for many men, perhaps for the majority; they dream of turning their back on what they have achieved (or failed to achieve) and starting out on an entirely new path, but few ever take even the first step toward translating such vague desires into reality. Thompson was one of those rare few, and that he happened upon the new path accidentally does not diminish the rarity of what happened.

At this midpoint of his life, he abruptly abandoned everything that was familiar to him and moved into a world and a career as exotic as any novelists creation. What is more remarkable, he found in this new world, again by chance, a fulfillment of certain innate talents that not only brought him personal satisfaction but also profoundly changed the lives of thousands of other people. In the twenty years before his ill-fated holiday in Malaysia, he had accomplished more than most men in a full life. He had built a major industry in a remote and little-known country whose language he never learned to speak; he had become an authority on an art that, previously, he scarcely knew existed and had assembled a collection that attracted scholars from all over the world; he had built a home that was a work of art in itself and one of the landmarks of Bangkok; and, in the process of doing all this, he had become a sort of landmark himself, a personality so widely known in his adopted homeland that a letter addressed simply Jim Thompson, Bangkok found its way to him in a city of three and a half million people.

Thompsons career in Thailand became one of the most popular postwar legends of Asia, recounted in dozens of publications and gathering, along the way, all the usual embroideries and distortions common to legend-makingsome of them, it is only fair to say, invented by the subject himself. It was quite characteristic that only a week before he went to Malaysia he was interviewed for yet another telling of it by an American television crew. Given such renown, it is not surprising that his disappearance attracted widespread attention. What was less expected was that the disappearance should acquire a legendary life of its own, with even more distortions, one in which the man himself has been all but lost amid the fascinations of the mystery.

The following account has two purposes: to tell the first Thompson story in greater detail than has been possible in other published versions, and to examine the second more closely and comprehensively than has been done. It is based on numerous interviews with people who were close to Thompson, on private letters, on all the material that has been printed concerning his career and disappearance, and on numerous conversations the author had with Thompson over some eight years in Thailand. When it was first written, less than three years after the disappearance, Thompson was still legally alive, and there were various reasons for omitting or playing down certain aspects, particularly concerning his private life. This gave rise to certain misconceptions, some of which seriously affected conclusions drawn from them; in this revised telling of the story, an effort has been made to fill in some of the gaps and produce a portrait more in keeping with the man known to his close friends and associates, as opposed to the numerous impressions, both oral and written, that have come from people who, despite their claims, knew him only slightly at some stage in his life or, in some cases, not at all.

Even a casual reader will soon perceive, however, that Thompson, like most gifted men, was a complex person; and for this reason there are inevitably assorted points of view about different aspects of his life. No account of either the career or the disappearance is likely to meet with complete approval from the many people who admired and the few who disliked him. What follows aims at telling the truth but it does not, it cannot, claim to be infallible.

One could start the Thompson story at several places: with his arrival in Thailand, for instance, which is really the beginning of the first legend, or, more conventionally, with his birth and follow through chronologically. Considering the purpose of this book, it seems more suitable to begin at that dividing point where the first legend came to a sudden, tragic end and the second began its curious growth.

1

T he Cameron Highlands is a cool and picturesque hill station, some 6,666 feet above sea level at its highest point, in the central Malaysian state of Pahang. It was named after William Cameron, a British surveyor who in 1885 discovered what he described as a fine plateau with gentle slopes shut in by lofty mountains and soon afterwards developed by foreign settlers from the lowlands as a retreat during the hot season, following a practice already well established in other British colonies like India and Ceylon. There is no train or air service; the quickest way to get there is to fly to Ipoh, the capital of neighboring Perak state, and then hire a taxi to make the winding ascent to the resort. Ipoh, however, has little to recommend it to the average traveler, and most tourists who go the Highlands for a holiday prefer to drive from either Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital, or Penang, a pleasant island off the west coast. From the former, the drive takes about five hours, from the latter seven.