History

"When the Waters begin to retreat, the People return them Thanks for several Nights altogether with a great Illumination, not only for that they are retired, but for the Fertility which they render to the Lands. The whole River is then seen covered with floating Lanterns which pass with it... Moreover, to thank the Earth for its Harvest they do on the first days of their Year make another magnificent Illumination..."

Simon de la Loubere, A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam (1691)

The gold handle of a sword that forms part of the Royal Regalia.

Painting in the throne hall of the Chakri Maha Prasat, showing Sir John Bowring being received in audience by King Rama IV in 1855.

T he earliest inhabitants of what is today Thailand are known only in shadowy form, through the assorted tools and ornaments they created. Some of these have been found in Kanchanaburi Province, along the River Kwai, others elsewhere in the country. The most dramatic discoveries came in a tiny hamlet called Ban Chiang in the northeast. Here, from around 3600 BC to 250 AD, an enigmatic people not only cultivated lowland rice but practised the art of bronze metallurgy, at a time much earlier than previously suspected. They also lived in houses, wove textiles, had domestic animals and fashioned objects that showed a refined sense of beauty.

The origin of these people remains a mystery. So does their fate, though some experts suggest they may have been the first of a series of migrant groups who were attracted to the fertile Chao Phraya valley and river basin. Two of the most important arrivals here were the Khmers and the Mons. Khmer culture reached its culmination in the splendors of Angkor, in the 12th century, but they also established cities deep in present-day Thailand. The Mons founded the Dvaravati Kingdom in the western half of the Chao Phraya valley and produced some of the earliest Buddhist monuments; their ancestors still live in the area.

The Thais, who would become the predominant group, are thought to have migrated from southern China into northern Thailand during the 11th century AD. By the 12th century, several independent Thai kingdoms had been established in the north, where they formed a federation known as Lanna Thai. Some had penetrated down into territories theoretically controlled by Mons and Khmers. In 1238, two Thai chieftans joined together, overthrew a local Khmer commander and founded the kingdom of Sukhothai. Though it lasted only a little more than two centuries, Sukhothai was the scene of extraordinary development in art and culture, as well as in politics. Here the Thai alphabet was devised, and the first distinctly Thai forms of architecture and sculpture took shape; moreover, through a system of treaties and alliances, Thai power spread until it was felt over a considerably larger area than the country occupies today.

Ayutthaya, which ruled for four centuries, was a more complex kingdom, one that demonstrated to an even greater degree the Thai gift for assimilation. At its peak, in the 17th century, the capital was larger than London of the same period and as cosmopolitan. Besides the Khmers, Mons, Lao and Burmese with whom the Thais had co-existed for centuries, traders came from India, China, Japan and distant Persia. The first Europeans also arrived, and soon there were Dutch, English, Portuguese, and French "factories," or trading posts, doing business outside the walls of the city.

The remains of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya. Both these ancient capitals were laid out according to ancient Hindu cosmological patterns, with the sacred Mount Mem as the center This was also followed at Angkor Dominating the view of Ayutthaya is Wat Phra Ram, modelled on Khmer architectural style.

A foreigner of the 17th century, depicted in a gold-and-black lacquer painting.

Following the destruction of Ayutthaya by the Burmese in 1767, the capital was moved further south, first to Dhonburi and finally to Bangkok, both on the Chao Phraya River.

When King Rama I of the present Chakri Dynasty decided to relocate his capital from Dhonburi to Bangkok in 1782, one of his goals was to recreate the splendors of Ayutthaya. Outwardly, it was a traditional Thai capital, with traditional values. The king was still known as Chao Jivit, the Lord of Life. He was surrounded by arcane ritual and held absolute power over every aspect of his kingdom, from social matters to national defense.

Yet behind that facade, something new was stirring-or, perhaps more accurately, something as old as Sukhothai. King Ramkhamhaeng, the greatest of the rulers of the first capital, had established the concept of a benevolent, paternalistic monarchy, mindful of the needs of his people and accessible to them. This concept had not always been maintained in Ayutthaya, where rulers became increasingly aloof and even god-like, but early Bangkok saw a return to the ideal, along with deeply-rooted Buddhist beliefs. The king once more became a recognizable human being, explaining and justifying the various proclamations that issued from his glittering palace on the river.

By the time of Rama I's death, in 1809, stability had returned to the kingdom; his successors further defined the role of monarchy in Thai life, shrewdly adapting it to a world that was changing with bewildering speed as neighbor after neighbor fell under European colonial rule. Bangkok, too, began to prosper, spurred by increased trade that attracted a growing number of Chinese immigrants. While most Thais preferred traditional occupations like farming and government service, the Chinese concentrated on commerce and were largely responsible for the city's remarkable growth.

A map of Ayutthaya, a late 17th-century European drawing of a court mandarin, a detail from a temple mural showing foreigners, and a view of the royal barges at Ayutthaya.

The Chao Phraya River in the 1890s.

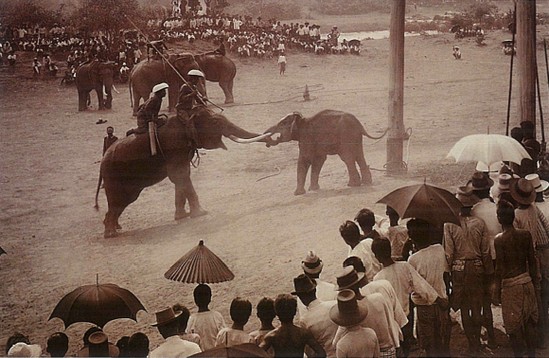

An elephant roundup staged in the old kraal near Ayutthaya, late 19th century.

To the average Westerner today, perhaps the best known of the early Chakri kings was Rama IV, or King Mongkut. Before coming to the throne in 1851, he spent 27 years in the Buddhist priesthood, a unique experience for a Thai ruler which in turn gave him unique insights into ordinary people's lives. He had travelled extensively, met foreign missionaries, learned English and French, and developed a keen interest in modern science; more than his predecessors, he recognized the danger of isolation, and through a series of wide-ranging reforms and treaties with foreign powers, he set his kingdom on a modern course.