Selected Bibliography

Bhilasri, Professor S., Thai Lacquer . Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 1989.

Bhilasri, Professor S., Thai Buddhist Art (Architecture) . Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 1963.

Brown, R., The Ceramics of South-East Asia . Oxford in Asia, 1988.

Brownrigg, H., Betel Cutters . Stuugart: Editions Hansjrg Mayer, 1991.

Charernsupkul, A., The Elements of Thai Architecture . Bangkok: Satri Sarn, 1978.

Clewley, J., The Many Sounds of Siam, in World Music . London: Rough Guides, 1994.

Conway, S., Thai Textiles . Bangkok: Asia Books, 1992.

Dumaray, J., The House in South-East Asia . Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Faculty of Painting and Sculpture (ed.), The Folk Art of Uthong, Sukhothai, Bangkok. Bangkok: Silapakorn University, 1996.

Farrelly, D., The Book of Bamboo . London: Thames & Hudson, 1996.

Fraser-Lu, S., Silverware of South-East Asia . Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Frdric, L., Buddhism . Paris: Flammarion, 1995.

Gosling, B., Sukhothai: Its History, Culture and Art . Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Graham, M. and Winkler, M., Thai Coins . Bangkok: Finance One Ltd., 1992.

Hallet, H., A Thousand Miles on an Elephant in the Shan States. Bang-kok: White Lotus, 1988.

Jumsai, S., Naga: Cultural Origins in Siam and the West Pacific . Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Kangkananda, M., Folk Crafts in Thailand . Bangkok: Silpakorn University, 1981.

Krug, S. and Duboff, S., The Kamthieng House . Bangkok: Siam Society, 1982.

La Loubre, Simon de, A New Historical Review of the Kingdom of Siam . Originally published in London, 1693.

Lair, R., Gone Astray: The Care and Management of the Asian Elephant in Domesticity . Rome: FAO, 1997.

Leesuwan, V., Thai Culture and Heritage . Bangkok: The Office of the National Culture Commission, Ministry of Education, 1981.

Leesuwan, V., Thai Folk Craft . Bangkok: The Office of the National Culture Commission, Ministry of Education, 1981.

Leesuwan, V., Thai Traditional Crafts . Bangkok: The Office of the National Culture Commission, Ministry of Education, 1981.

Moore, E., Stott, P., Suryavudh, S. and Freeman, M., Ancient Capitals of Thailand . Bangkok: River Books, 1996.

National Identity Board (ed.), Thai Life: Thai Folk Art and Crafts . Bangkok: The Prime Ministers Office, 1998.

National Museum Division (ed.), Thai Minor Arts . Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 1993.

Panjabhan, N., Silverware in Thailand . Bangkok: Rerngrom Publishing, 1991.

Panjabhan, N., Wichienkeeo, A., and Na Nakhon Phannom, S., The Charm of Lanna Wood Carving and The Art of Thai Wood Carving . Bangkok: Rerngrom Publishing, 1994.

Pattaratorn, C., Votive Tablets in Thailand . Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Phothisuntr, W., The Art of Mother of Pearl Inlay . Bangkok, 1981.

Prangwatthanakun, S., and Naenna, P., Chiangmais Textile Heritage .

Shan, J. C., Northern Thai Ceramics . Oxford, 1981.

Suksri, N. and Freeman, M., The Grand Palace . Bangkok: River Books, 1998.

Trakullertsathien, C., The Lost Art of Norah Performance . Bangkok: Bangkok Post, Outlook, 2000.

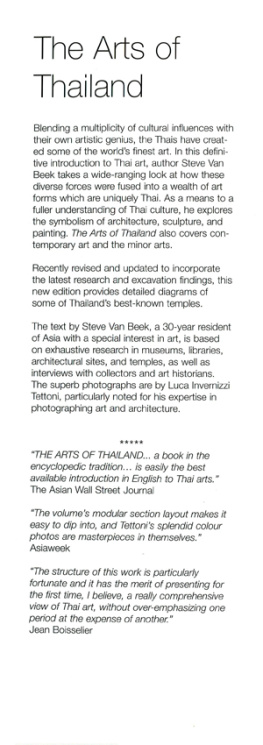

Van Beek, S. and Tettoni, L., The Arts of Thailand . Hong Kong: Periplus, 1999.

Wickremesinghe, K. D. P., The Biography of the Buddha . Colombo, 1972.

Wyatt, D. K., Thailand: A Short History . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

Yopho, D., Thai Musical Instruments . Bangkok: Department of Fine Arts, 1957.

Sources

The author and photographer would like to thank the following for their assistance:

M.R. Narisa Chakrabongse

Anongnart Ulapathorn

Mimi Lipton

William Booth

Neyla Freeman

Lanna

3 Denbigh Road

London W11 2SJ

Tel: +44 20 7229 6765

Fax: +44 20 7729 0027

www.lannadesign.co.uk

Piece of Art

River City

Room 451, 4 th Floor

23 Trok Rongnamkaeng Road

Smapantawong

Bangkok 10100

Tel: +66 2 237 0077

Fax: +66 2 237 0078 ext. 451

Rama Antiques

1238/12 corner Soi 36

New Road

Bangkok 10500

Tel: +66 2 235 7991

Fax: +66 2 236 8104

Email: ramaart@thaimail.com

Jim Thompson Thai Silk Company

9 Surawong Road

Bangkok 10500

Tel: +66 2 632 8100

Fax: +66 2 236 6777

Email: office@jimthompson.com

Decorative Arts

Items Created for Royalty and Wealthy Patrons

In what was until recently a highly structured society, the most skilled artists and craftsmen were requisitioned for work at the royal court, and a clear distinction existed between these specialists and those who worked in the villages. They were known as chang sib mu , meaning artisans of the ten types, and while they may have originally been drawn from the same pool of craftsmanship, their specializations were in courtly productions, including draughts-men and gilders (the first category), lacquerers, wax-modellers, fretworkers and fruit and vegetable carvers. To this day, a few have their ateliers within palace grounds.

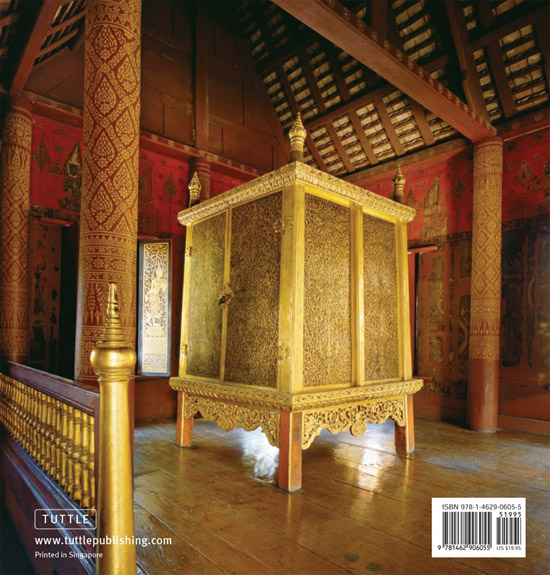

The interior of the Lacquer pavilion, a former scripture library, at Suan pakkard palace, Bangkok.

Lacquerware

khrueang kheun

One of the most important traditional crafts in Thailand, the manufacture of lacquer receptacles is heir to a long Asian tradition, of at least 3000 years, almost certainly originating in China. In its basic form, Thai lacquerware is undecorated and highly functional, although its inherent beauty may disguise its utilitarian nature. Well-applied lacquer has a remarkable range of characteristics, being light, flexible, waterproof and hard. It resists mildew and polishes to a smooth luster. Indeed, it has many of the qualities of some plastics, but with the advantage of being a naturally evolved product from local materials.

Lacquer in Southeast Asia comes from the resin of Melanorrhea usitata , a fairly large tree that grows wild, up to an elevation of around 3,000 feet (914.4 meters) in the drier forests of the north, and is similar to the sumac tree of China and Japan, Rhus vernicifera . It is completely unrelated, incidentally, to the shellac used in Europe and India, which is the secretion of an insect.

In Thai, lacquerware is called khrueang kheun (khrueang meaning in this case works), and this gives a clue to its origins. The Tai Kheun are an ethnic Tai group from the Shan States in Burma, and after the 1775 re-capture of Chiang Mai from the Burmese following a lengthy period of war, the new ruler, Chao Kawila, forcibly moved entire villages from Shan to re-populate and revitalize the city. This kind of re-settlement after victory was a common practice in the period, and craftsmen were particularly valued. One community, of lacquer workers, settled in the south of the city and their name became, for the Thais, synonymous with lacquer.

Although lacquer can be and often is applied to wood, its original, pure use was over a carefully made wicker base structure. This allows two of the finer qualities of the lacquerits lightness and flexibilityto dominate. In fact, with a well-made bowl it should be possible to compress the rim so that the two opposite sides meet, without cracking or deforming it. The process is expectedly time-consuming. The form is first made using splints of hieh bamboo, and these must be of the width and thickness appropriate to the size of the object. If they are too big, the gaps between them will be too wide to take the coating of lacquer. The best time considered for applying lacquer is towards the end of the rainy season, when the atmosphere is moist but not too hot. The resin is applied in a number of layers, each of which must dry completely before receiving the next coat, and the entire process can take up to six months (very unlikely nowadays, of course!). The resin, known as rak in Thai, has varying admixtures at different stages. Often, the first layer has been mixed with finely ground clay to help it fill the gaps in the wicker-work, while the last and finest layers are mixed with ash, from burnt rice, bone or cow dung.