Written in memory of my father

Donald McCloud, Engineer

Contents

A hundred times every day

I remind myself that my inner

and outer life are based on the

labours of other men, living

and dead, and that I must exert

myself in order to give in the

same measure as I have received

and am still receiving.

Albert Einstein,

The World As I See It

This book is something of a manifesto for how we can live. Its a manifesto for a way of living that, in comparison with life of the last 60 years, could be slower, more enjoyable, gentler and altogether less taxing on the resources of this planet. It calls for a new appreciation of the magical human effort and energy that go into designing and making everything around us, from a spoon to a car, from a house to a city, from a dam to a cathedral. It calls for a re-evaluation of materials and fuel energy, and it calls for a culture in which we share much more of what we have in order that we dont squander it.

I think we have lost touch with the made world. We have forgotten how difficult and time consuming it is to make something; how hard it is to make an elegant table out of a tree or a spoon out of metals dug out of the ground and refined. Our sensibilities to craftsmanship have been eroded by high-quality machine manufacturing; our tactile sense has been debased by a plethora of artificial materials pretending to be something that they are not. Our attention, meanwhile, has been diverted by the virtual built worlds that exist inside screens. The landscapes of gaming and avatar worlds, for instance, are not complicated by the inconvenient messiness of the real world. In them, stuff, narratives, buildings and people are both perfect and disposable. Need some money to beat your friends in Super Mario? You can earn that in 15 seconds simply by jumping over a log. Need more ammo to blow people up? Press button B.

The real world is not perfect and its not disposable. In the real world, things and people age and decompose. The real, tangible world is much harder to make, more difficult to maintain and unpleasant to recycle. Which may explain why so many people seek solace in virtual worlds, even if its just by watching a soap opera on TV.

My Big Point is that I find the real world, which man has shaped, layered and renewed over thousands of years, more exciting and energizingdespite its grimethan any 3-D movie effect. Watching the Brooklyn Bridge explode in a computer-animated sequence may be awesome, but it is never as awe-inspiring as standing underneath the real thing and wondering how men managed to make it. Awesome is loud but awe is quiet.

Im aware that my manifesto is motivated by a passionate love for places, buildings and things, not as objects that I want for myself to keep but as examples of human brilliance and creativity, the experience of which I want to share. Im also frustrated, having worked as a designer and maker, by how little craftsmanship and the sweat of labour are appreciated nowadays. How we all assume that everything around us is made by machines and computers, whereas the truth is that your dinner plate was probably made by just three people in Portugal who spent four months of their lives producing a range for a high-street retailer; and your mobile phone was assembled by one person over a morning of their life.

So Im writing out of a passionate love for the built environment and a quiet anger over how it is passed over in pursuit of temporary diversions and virtual pleasures when it can offer some of the greatest pleasures of all. The result goes something along the lines of What do we want? A much better appreciation of the things around us so that we can cherish them, live a more sustainable life and enjoy a richer relationship with our world. When do we want it? Quite soon, please, and quickly. But not too quickly, because its all meant to be about lingering to enjoy the moment, isnt it?

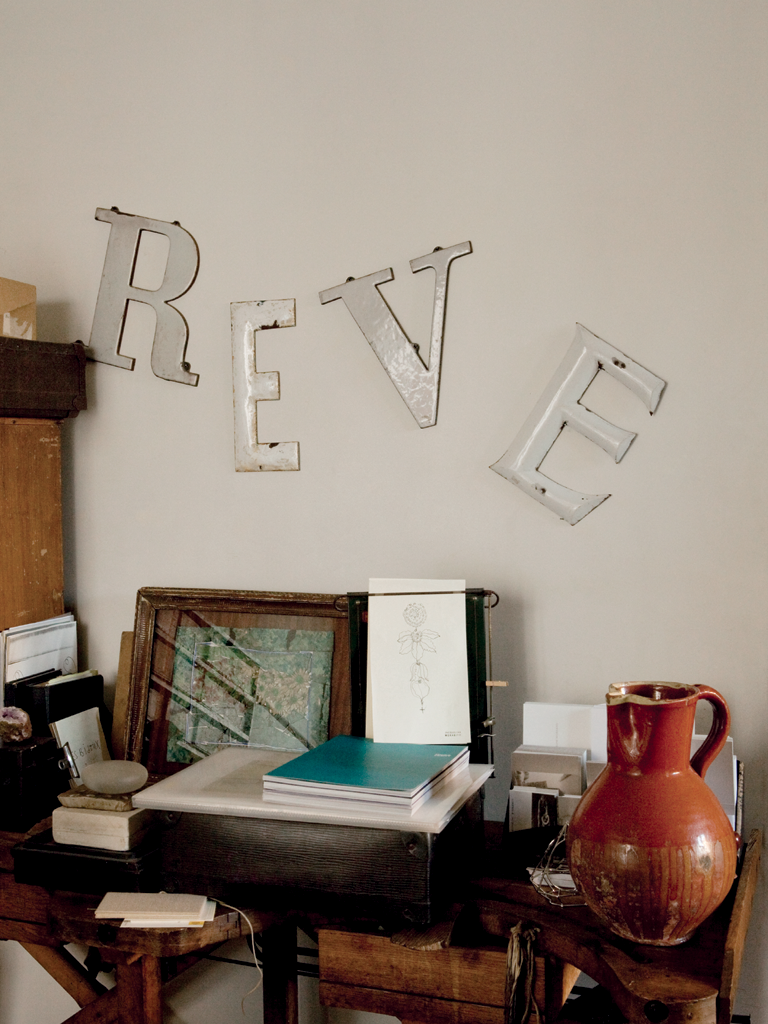

After the Slow Food movement, maybe its time for the Slow Living movement. That sounds dull, doesnt it? In fact, slow is the wrong word. It should be the Take Your Time movement (which is really what the Slow Food movement should be called). Take your time to appreciate whats around you, to explore your environment, to savour experiences and to develop relationships with the objects around yoube they a car, a vase or a townas examples of human brilliance and human energy. In fact I do have a name for this softer, richer, more fulfilling experience. I call it New Materialism. Sometimes I call it Contextual Materialism, which sounds even more pretentious. In truth it contributes to a wider set of values that the charity BioRegional calls One Planet Living, which sounds far more approachable.

Youll have noticed that in the paragraph above I slipped in that slippery word sustainable. It doesnt occur too often in this book because its a term already over-used, so tried on by so many people, institutions and companies that its stretched and gone all loose and floppy. Sustainability is now a big baggy sack in which people throw all kinds of old ideas, hot air and dodgy activities in order to be able to greenwash their products and feel good. Politicians speak of sustainable economic growth (this is not necessarily ecologically or socially beneficial), which is not the same thing as growing an economy sustainably. Oil companies talk of sustainable oil exploration. My dictionary tells me that sustainable means tenable or able to be maintained at a certain rate or level; also conserving an ecological balance by avoiding depletion of natural resources but also able to be upheld or defended (nice one for the oil industry there).

I try not to use the S word too often, despite the fact that this books big theme is how we implement the culture change that is going to be necessary over the next 40 years, in order that a global population of what will be nine billion people (currently around seven) can still be sustained by this planets resources.

As long ago as 1998, commentators and academics were criticizing the overuse of sustainability as a catch-all term for the durability of environmental, business, economic and social policies. Peter Marcuse, a planning professor at Columbia University, has pointed out that separate applications of the word to housing, planning, the environment and our use of resources can contradict each other: what is sustainable in the layout and organization of a community in a city may not be environmentally defensible, for example. Recycling our beer cans and working at home more will not deal with the problems of the over-exploitation of the planets resources and climate change:

The long run entails conflict and controversy, issues of power and the redistribution of wealth. The frequent calls for us to recognize our responsibility for the environment avoids the real questions of responsibility, the real causes of pollution and degradation. The slogan of sustainability hides rather than reveals that unpleasant fact.

Next page