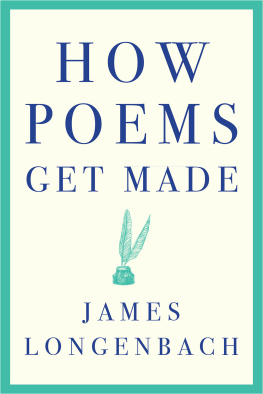

Also by James Longenbach

Poetry

The Iron Key

Draft of a Letter

Fleet River

Threshold

Prose

The Art of the Poetic Line

The Resistance to Poetry

Modern Poetry after Modernism

Wallace Stevens

Stone Cottage

The Virtues of Poetry

James Longenbach

GRAYWOLF PRESS

Copyright 2013 by James Longenbach

Fan-Piece, For Her Imperial Lord by Ezra Pound, from Personae , copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, Amazon.com, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-637-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-55597-067-3

First Graywolf Printing, 2013

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012953981

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder Design

Cover photos: Walker and Walker, The Image Bank, Getty Images (top) / Copyright Karen Ilagen, Flickr, Getty Images (bottom)

T he source of poetry is always a mystery, an inspiration, a charged perplexity in the face of the irrationalunknown territory. But the act of poetryif one may make a distinction here, separating the flame from the fuelis an absolute determination to see clearly, to reduce to reason, to know.

Cesare Pavese

Preface

T he best poems ever written constitute our future. They refine our notions of excellence by continuing to elude them. Any utterance affords us an opportunity to think about diction, rhythm, structure, and tone, but by asking to be heard as well as understood, poems intensify our relationship with the medium, the medium we harness every day. No great poem ever stood in the way of the future, foreclosing imaginative possibilities by asking us to endorse a narrow vision of our past or a sectarian arrangement of our contemporaries.

But over the past fifty years, accomplishment in our poetry has been signaled most often by manneras if it were the job of artists not to engage the most potent aspects of Dickinson or Eliot but to sequester themselves in one or another schoolroom, buoyed by the camaraderie with other students sitting obediently, if stylishly, in rows. Schoolroom for formalists, schoolroom for experimentaliststhe degeneration of these terms, hijacked by the renegade engines of taste, would portend the degeneration of the medium, except that while fifty years is a long time in the life of an artist, it is in the history of art nothing, the blink of an eye.

This is why the previous fifty years of poetry almost always seem mannered; they seemed so to Yeats a hundred years ago, they seemed so to Keats a hundred years before that. In the short run, the schoolrooms are driven by a mode of writing that can ix be learned from like-minded contemporaries, releasing poets from the work of learning from inimitable predecessors. But in the long run, Keats did not become Keats by hanging out with Leigh Hunt; he became Keats by spending long, rich hours with Shakespeare and Milton, poets whose virtues he dissected word by word.

This book proposes some of the virtues to which the next poem might aspire: boldness, change, compression, dilation, doubt, excess, inevitability, intimacy, otherness, particularity, restraint, shyness, surprise, and worldliness. The word virtue came to English from Latin, via Old French, and while it has acquired a moral valence, the word in its earliest uses gestured toward a magical or transcendental power, a power that might be embodied by any particular substance or act. With vices I am not concerned. Unlike the short-term history of taste, which is fueled by reprimand or correction, the history of art moves from achievement to achievement. Contemporary embodiments of poetrys virtues abound, and only our devotion to a long history of excellence allows us to recognize them.

Certainly there are more virtues than the ones I emphasize, nearly as many as there are poems. So while any of the books chapters may be read on its own, the chapters are designed to be read in sequence, every poem both challenging and consolidating the embodiments of excellence surrounding it. Sometimes the chapters address each other explicitly, either by opposition (boldness and shyness) or by partially overlapping (boldness and excess). Implicitly the chapters address themselves. The same poet may embody virtues that initially seem unrelated (Shakespeare representing both dilation and surprise) or opposed (Yeats representing both change and inevitability), suggesting that our notions of excellence are not as stable as one might have imagined, also that the poets are themselves more various than any set of virtues may allow. How do we describe the allure of wild excess when we are confronted with the irresistible seduction of restraint? Why does the power of a great poem feel simultaneously unpredictable and assured?

No virtue may be assumed, except inasmuch as it is evinced in a particular way by a particular poem: my interest lies not in abstract notions of excellence but in the ways in which such notions are enacted in language. As Cesare Pavese says in my epigraph, the art of poetry is produced by an absolute determination to see clearly, to reduce to reason; even the thrill of disorder is produced in art by exquisitely crafted means. But as Pavese also says, the source of poetry is an irrational mystery, never to be reasoned, and I also spend some time examining, usually through letters, the lives that these poets have transmuted so painstakingly.

The poets I discuss are hardly unfamiliar; besides the ones Ive mentioned so far, Ill also be talking about Donne, Blake, Whitman, Pound, Bishop, and Ashbery, among others. Some poets will be treated at length, and some will need to be discussed more quickly. But the relationships between the poems are as important to me as the poems themselves. Openness is everywhere assumed. That the poets are familiar is a mark not only of virtues we might take for granted but also of a future we might sidestep or dismiss, mistaking it for the past.

The Virtues of Poetry

The Various Light

C elebrating the painter Elstir, the narrator of In Search of Lost Time suggests that for the great artist, the work of painting and the act of being alive are indistinguishable. Certain bodies, certain callings, certain rhythms may confirm our ideals so inevitably, says Proust, that merely by copying the movement of a shoulder, the tension of a neck, we can achieve a masterpiece. The implication here is that art is not the product of the will. More than lack of ambition, it is the inability to surrender to our inevitable callings and rhythms that keeps us from fulfilling our promise.