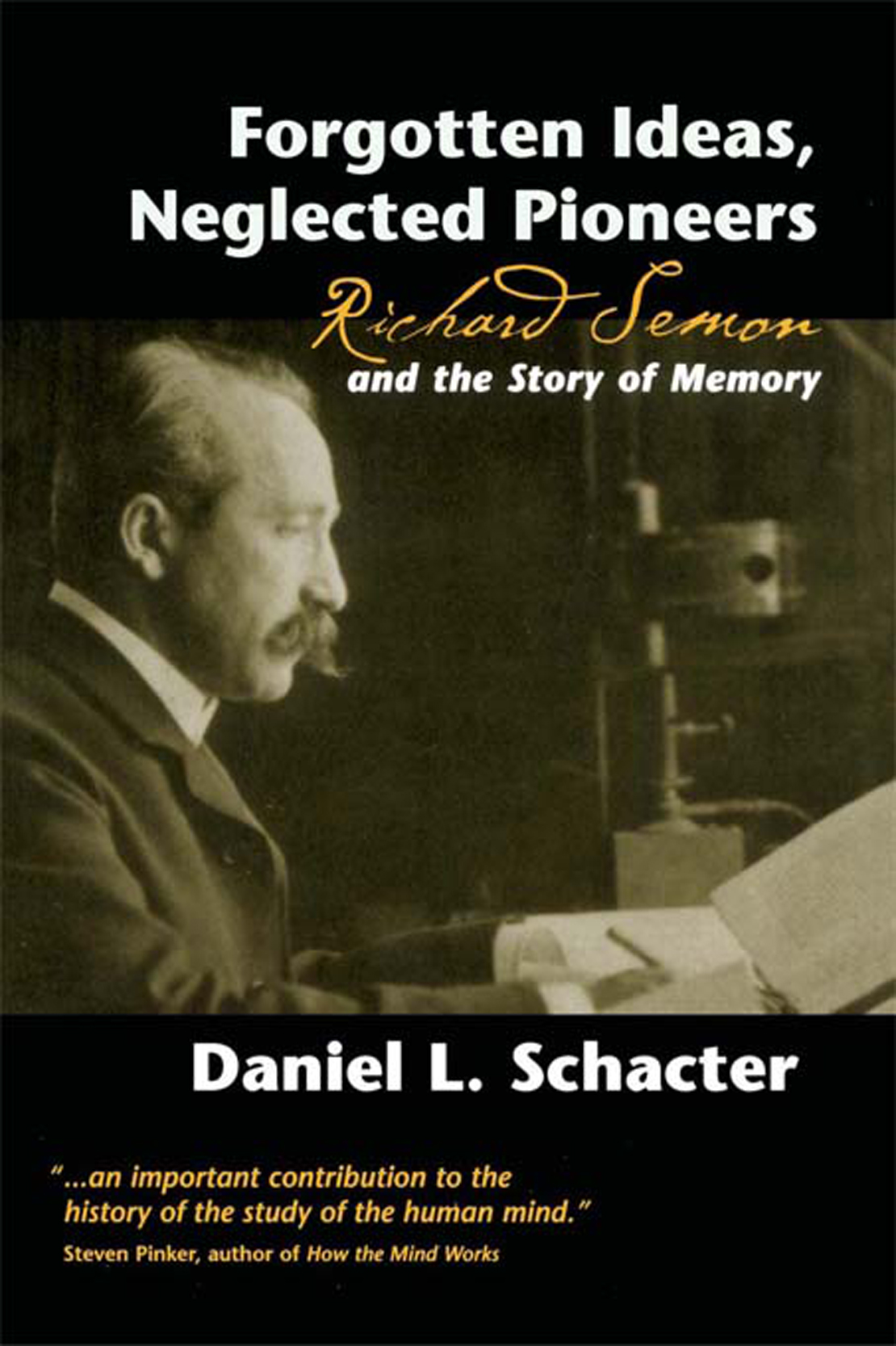

FORGOTTEN IDEAS,

NEGLECTED

PIONEERS:

Richard Semon

and the Story of Memory

Daniel L. Schacter

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

First published by Psychology Press

This edition published 2011 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

FORGOTTEN IDEAS, NEGLECTED PIONEERS: Richard Semon and the Story of Memory

Copyright 2001 Daniel L. Schacter. All rights reserved.

Cover design by Nancy Abbott.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schacter, Daniel L.

Forgotten ideas, neglected pioneers : Richard Semon and the story of memory / Daniel L. Schacter.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Semon, Richard Wolfgang, 1859-1918. 2. Memory. I. Title.

ISBN: 978-1-84169-052-0 (paper)

In memory of my father,

Philip Schacter

Contents

Preface

A lthough I did not know it at the time, this book was conceived on a rainy afternoon in March, 1977, when Eric Eich and I, both graduate students in experimental psychology at the University of Toronto, discussed the usefulness of the term ecphory in the analysis of human memory. About a year later, after becoming familiar with the imaginative work and dramatic life of the inventor of the termRichard SemonI decided to write this book. The resulting monograph is a blend of biographical, historical, and psychological materials, and has two major purposes: To tell a story, and to examine substantive issues in the history and psychology of science that are related to the story.

Several of the issue-oriented chapters investigate little explored areas in the history of scientific thinking about memory, including Semon's contributions to memory theory. I anticipate that these chapters will be primarily of interest to cognitive psychologists, although they are also relevant to historians and scientists concerned with the interaction between psychology and evolutionary biology. Other chapters address wide-ranging problems in the psychology of science that have not yet received serious attention. I hope that my treatment of these problems is sufficiently broad to interest readers from many areas of psychology, as well as from cognate disciplines such as history and sociology of science. The discussion of all these issues, however, is preceded by the story of a rather remarkable life that I suspect will appeal to readers with diverse backgrounds.

Acknowledgments

T he undertaking and completion of this book has been made possible by help from numerous individuals and institutions. My research was initially supported by a National Science Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship, and then by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. I also gratefully acknowledge the support my research received from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant No. A8632 awarded to Endel Tulving. Work on the book was initiated during my stay at the Department of Experimental Psychology, Oxford University, in 1978: I thank all of the members of the department who made my time at Oxford so enjoyable.

The staff at the Bodlean Library, Oxford, and Robarts Library, University of Toronto, frequently aided my efforts by locating materials that were difficult to find. The Bavarian State Library in Munich permitted me to inspect and make copies of letters written from Ernst Haeckel to Richard Semon. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Professor Huldrych Koelbing and the rest of the staff at the Institute of the History of Medicine in Zurich. Professor Koelbing gave me access to the Institute's collection of letters written from Richard Semon to August Forel, and encouraged my research in a spirit of scholarship that I will always remember fondly Mrs. Majorie Semon graciously assented to spend an afternoon with me discussing what she knew about the Semon family, and also permitted me to reproduce her photographs of Sir Felix Semon.

Many of the source materials for this book were in German. Agnes Kocsis aided my work by doing excellent translations of the numerous (and frequently illegible) letters written by Semon to Forel, and by Haeckel to Semon. The other translations from the German are my own, but it should go without saying that I am responsible for all of the translations in this book. I also extend my thanks to Hugo Stckel of the International Summer Courses in Mayrhofen, Austria, a master teacher who vastly improved my ability to read German during a delightful month in his summer course.

My ideas about the book have developed and changed during the course of conversations with numerous colleagues: I thank them collectively because the list is a long one. Part or all of the manuscript has been read and commented upon by Eric Eich, Lawrence Erlbaum, John Furedy, Agnes Kocsis, Middian Kurland, Michele Stampp, Endel Tulving, and Polly Winsor. Many of their comments and criticisms have helped me to structurally, substantively, and stylistically improve the manuscript. I am, of course, alone responsible for the final contents of the book. Several of my debts should be individually acknowledged. Michele Stampp provided extensive emotional and practical support during the later phases of this project, and also contributed useful comments and questions about the manuscript. I owe many thanks to Lawrence Erlbaum, who has taken a keen interest in the book since its inception; he has been a source of both encouragement and incisive editorial guidance. Endel Tulving has contributed to this project in many ways: By having faith in my ability to complete the book and also do a satisfactory Ph.D. thesis; by aiding my research efforts during the past several years in ways too numerous to list; and by taking the time to carefully read the entire manuscript and discuss it at length with me. I am deeply appreciative of all of his efforts. Finally, I feel somehow compelled to thank Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart for his twenty-seven piano concertos. They constituted endlessly interesting contexts for the pursuit of much of the work.

Daniel L. Schacter

Toronto, Ontario

Foreword

A mong the smartest people in psychology and related sciences are graduate students. And, along with the rest of humanity, they are getting smarter year by year, as specified by the well-known Flynn effect. Thus it has come to be that, especially as they get close to the end of their pre-doctoral careers, ready to be called doctors, they know, or at least think they know, everything. That is, everything that is worth knowing. Whatever they do not know, by definition, is not worth knowing.

These smart people know what is important in the world of science and what is not. This latter category clearly includes history of psychology, and indeed history of anything. The important problems and ideas that matter originated some five or ten years before the budding scientists themselves entered graduate school. Whatever little happened earlier in the past is unimportant and immaterial, and not worth wasting any time on. History is for old folks, aging full professors who have nothing better to do than to amuse themselves with irrelevancies. Whatever these oldies say or write on the antiquities can be safely ignored, because it possibly cannot make any difference in the real world, here and now, and perhaps tomorrow. (I happen to be privy to these kinds of beliefs of most eager young researchers not only because I have seen quite a few in my life but also because, a long time ago, I was one myself.)