J. E. As with all academic books, this one has been a long time in the making, although for all sorts of personal reasons, it took even longer than normal! I am extremely grateful for Betsys hard work throughout the whole collaboration but especially at the very end when, due to a sudden health crisis, I had to step back completely and she had to take on the entire thing at a very critical stage. I also wish to thank our excellent contributors for their hard work and unending patience as the book made its slow progress. Our contributors were always prompt with drafts and responsive to comments and this made the process far easier than it might have otherwise been. We would also like to thank Eileen Cadman for her help preparing the manuscript and for her incredible attention to detail. I am, as always, eternally thankful to Don for not only his professional advice and support, but his care and loving support while also keeping the home fires burning. This book is dedicated to my parents whose tireless love and care has always been a bedrock of stability and support throughout my life, but never more so than during stressful months of illness and treatment.

E. W. First of all, I would like to thank my co-editor, Jo, for her tireless cheer and endless resources of energy, without which this project would not have gotten off the ground. I will remember fondly our virtual collaboration punctuated by intense, in person, work sessions when one or the other of us could get across the pond. I am also grateful to Don Slater not only for his brilliant collaborative contribution to this volume, but also for letting Jo go so many times, holding down the fort and caring for kids, while she was either away in New York, or busy at home as we feverishly worked at the kitchen table, her desk, or wherever we found space for two computers and a lot of energy and excitement. My heartfelt gratitude also extends to Kristin Miller, whose vast organizational skills, kindness and willingness to not only track down resources, but to also be a sounding board for ideas, consistently made her research assistance both a joy and also a necessity that I miss to this day. Thanks also to the institutional support of the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship in the Humanities, the BMCC/CUNY Faculty Development Grant for supporting the writing of some sections of this book and the PSC CUNY Research Award Grant, without which I would not have been able to afford Kristins consummate skills. For her assistance in connecting me to modelling professionals for portions of my research presented here, a huge thanks goes to Renee Torriere. I am also grateful to Sage publications for allowing me to reproduce the article, Modeling Consumption: Fashion Modeling Work in Contemporary Society, which appeared in the Journal of Consumer Culture , 9/2: 27396. Thanks too are in order to Dan Cook for giving us the opportunity to present ideas in a conference setting which ultimately germinated into the core of this book. We are also grateful to our authors for their fine scholarship and collegiality. And finally, I have to thank Patrick; he knows the reasons why.

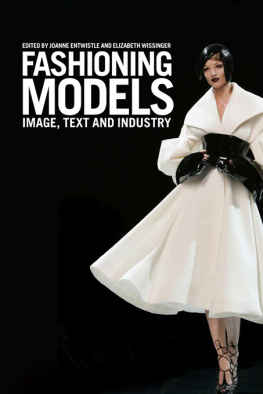

Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wissinger

Why an academic book on fashion models? What can we learn from scholarly analysis of such cultural ephemera? Indeed, what, if anything, can we say about fashion models beyond the obvious and oft-made tabloid/newspaper points about their supposedly unhealthy size or decidedly problematic status as iconic female role models? This book, we hope, answers some of these questions by analysing the cultural appeal and significance of models. While we cannot dismiss the column inches models now command in newspapers and magazines, there is more to fashion models and modelling than the sensational stories we read about in the popular press. Moreover, it is this very fascination with models as popular cultural entities that demands a more thorough, scholarly analysis because, despite their apparent triviality, models actually occupy an interesting and influential place within the social world. By examining the fashion model as contemporary figure, and the practices of fashion modelling as contemporary image industry, there is much to be discovered.

This collection explores how models have been integral to the development of modern consumer culture, and as such, have become a barometer of the current state of attitudes towards women, race and consumerism. From the long-stemmed American beauties celebrated in the 1920s by the First American model agent John Robert Powers selling soap to the masses, to the hyper-marketing campaigns fronted by the supermodels of the 1980s, models have played a critical role in shaping how commodities are sold to us. Captivated by images and lifestyles of fashion models in sleek and glossy photographs and on the runways and catwalks of the fashion capitals, on the one hand, we are simultaneously repelled by images of the often extreme aesthetics of jumbled limbs and gaunt faces embodied by super-skinny waif-like models. Consequently, models have become antagonistic and even repellent or at least uneasy characters in a moral drama about modern womanhood. Despite (or perhaps because of ) these mixed messages, fashion models have an enduring appeal in contemporary visual culture.

The voracious consumption of stories and images of models thus articulate not only a fascination with the seemingly glamorous lifestyle of models, but also the apparent dark underside of the industry. When Kate Moss was caught on a mobile camera allegedly snorting cocaine, the images flashed around the world and caused widespread debate and controversy about models behaviour and lifestyle. Models have also been at the centre of controversies concerning the female body, such as the outcry against the size zero aesthetic, which has been condemned and vilified in the worlds press in recent years. When a twenty-two-year-old model died after stepping off a runway during a fashion week in Montevideo, South America, in 2006, countless press conferences, and everyone from media pundits, bloggers and international newspapers, jumped at the chance to cover a story that not only stirred outrage, but also afforded the opportunity to display provocative pictures of suffering young women. The vitriolic rhetoric surrounding the tragedy, coupled with the deaths of two other models (Hennigan 2007), spurred the organizers of Madrids Fashion Week to ban models with a height-to-weight ratioor BMIbelow 18 (Klonick 2006). Milan quickly followed suit, with a code of conduct to protect young models vulnerable to anorexia and exploitation (Duff 2006). While the UK and USA did not exactly ban skinny models, the amount of controversy demanded action, and head fashion organizations in both countries issued guidelines and called for training industry personnel to recognize signs of bulimia and anorexia (Wilson 2007; Thorpe and Campbell 2007). There were even two body image summits in the UK. As these examples demonstrate, images and stories of fashion models consist of moral dramas that focus attention on their bodies as in some way excessive, abject, as well as desirable. These fixations have produced wave after wave of moral panics about models effects, from fears about their supposed influence on the rise in eating disorders among young women, to concerns as to the possible promotion of a hedonistic, drug-taking lifestyle.

To situate models within modern-day dramas of femininity also requires us to consider how modelling has become an idealized occupation for girls and young women; the new Cinderella offering the promise of a fairytale fantasy life of glamour and adoration. One way in which this lifestyle is sold to young girls is through the reality TV formats that flood the international TV channels and which promote the modelling life. Whereas once girls and women could only consume images that models producedin advertisements and fashion editorialsthey are now in a position to consume the lifestyle backstage through such formats as Americas Next Top Model .

Next page