A version of Ernst Barlach: Materiality and Production was presented at the 2009 Heidegger Circle meeting at Xavier University in Cincinnati. A portion of Bernhard Heiliger: The Erosion of Being was presented at the 2006 IHUM Fellows Research Colloquium at Stanford University and subsequently at the 2008 Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy meeting at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. A portion of Eduardo Chillida: The Art of Dwelling was presented at the Heidegger and Space symposium at Stanford University in 2007 and subsequently at the Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy meeting at George Mason University in 2009. An abbreviated version of all four sections was presented at Stony Brook University in 2007. I am grateful to the organizers, respondents, and interlocutors at each of these engagements: Phaedra Bell, Andrew Benjamin, Edward S. Casey, Wayne Froman, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Robert Harrison, Eduardo Mendieta, Richard Polt, Mary Rawlinson, John Sallis, Thomas Sheehan, Ingvild Torsen, Donn Welton, Laura Wittman, and David Wood. Professor Caseys own thinking of space has been an inspiration throughout.

This work would not have been possible without the cooperation of the estates and institutes preserving the work of these artists. For its completion, I am obliged to Anja Maslankowski at Ernst Barlach GmbH & Co., KG; Sabine Heiliger for her tremendous help at the Bernhard Heiliger Stiftung; Nausica Sanchez at the Museo Chillida-Leku; Elizabeth Tufts-Brown and Laurel Mitchell at the Carnegie Museum of Art; and, last but not least, the generous assistance of Urs Ullmann, manager of the Erker-Galerie in St. Gallen, Switzerland. A subvention grant from Emory Universitys College and Graduate School generously supplied the permission costs for the images reproduced.

Conclusion

THE TASTE OF US

Sculpture is a matter of articulation, the art of limits. But rather than circumscribing a completed work, articulation is a way of remaining incomplete. The articulated body is not self-standing; it transpires with its environs, it marks and is marked by what is other to it. Sculpture stages this fact of exposure, of incompletion as belonging to a world. Each of the sculptors with whom Heidegger concerns himself explores this fact. The degeneracy of Barlachs sculpture lies in the formlessness that literally informs his work. The well-defined faces and hands of these sculptures emerge from the incomprehensible and unexplored masses at their heart. Barlachs work shows the formless other that inhabits every body, our own included, and gives us to understand that even the exposure of existence would be impossible without this unshaped material earthliness. Heiligers sculpture records the struggle of existing in a world beyond ourselves that is never empty or void but that operates with a material force to weather and wear us down. The decaying effects of exposure reveal exteriority to be ever entering us, riveting through us, exiting us, and drawing us out of ourselves, making the outside a part of us. Chillida begins with a conception of form as always emanating beyond itself, with sculptures that not only echo and reverberate a silent music but that invite the medium to blow across their surfaces as well. Chillida and Heidegger agree in finding this middle ground, this between, to be the only possible site for a dwelling that is particularly humanthat is, relational and tied to surrounding people, places, and things. Such a connection is even more evident in the receding and supportive empty space of sculpted reliefs, such as the Athena reliefs discussed earlier, and it is no coincidence that each of these three sculptors also worked in relief.

Sculpture stages a respiration between body and world. The space of sculpture differs from the space of the everyday world of traffic and commerce, conducting our thought along different paths and slowing all movement from point a to point b . Sculpture thickens space, gathers it together and knots it in ways that are felt throughout its surroundings. The sculptural bending of space warps our intentions away from their targets to trail off indefinitely, leaving us behind, unsatisfied and exposed before the work. We fail ourselves before the work and fall exhausted before its radiance. Sculpture is a testament to exposure, to the fact that we are dissolving in space . The work runs through us and carries us along with it. Our concerns extend beyond ourselves, our bodies do not end at our skin, our bodies are beyond ourselves, our concerns make up our skin. There is nothing but skin for such a disorganized (nonutilitarian) body, skin understood as surface of sense, as unfurling sheets of sheer phenomenality. We so fully belong to this world that it bears our scent, our taste, we dissolve into it and soften the edges of dwelling. Sculpture reveals to us our inextricable belonging to world.

Such a space is far from empty. All that appears participates in this space and is drawn out by it. All that appears lends space its weight. There is no frictionless or lossless space. It abrases us and weathers us. We are weathered by exposure. We are dissolving in space . The concerns of the body ripple through this medium, formulated by it, never-ending into it. The metaphysical conception of space as voidthis too is nonetheless nothing alien to the mediality of space (and it should be clear by now that there is nothing alien to the mediality of space; we are prepared for everything). Such conceptions only serve to vary still more the tensions of space, furthering the conditions of its material conducting.

The world flows through us and buoys us along, ebbing and flowing, drawing us out and relating back to us. Such a rhythmic emanation is definitive of place. The withdrawal of being that opens place (a withdrawal that needs to be mistaken for void), that lets place be a matter of relation, reverberates through these places, unsettling them. These reverberations of place echo through us, too, as rhythm. Rhythm, Heidegger claims, is the relation bearing human beings ( GA 13: 227); by undulating through us it sways us further into the world. Rhythm can overtake us. Sculpture syncopates the world. Sculpture is the art of spatial rhythm which seeks us out and enters us, attuning us to its sinuous invitation: that we dwell here in the midst of its radiance.

But if sculpture lures us out of ourselves by entering into us, if it interrupts our doings by a thickening of space that allows its rhythm to take hold, then it does so only to reveal to us our mediality, that we exist outside ourselves to such an extent that we are the world. Things plunge into this abyss of the world, they shine in their appearing, streaking by as they fall. Everything falls and runs past its borders ( panta rhei ; ). Sculpture reveals to us our mediality by making visible the invisible (world). Every sculpture performs this impossible task differently. Sculpture is the articulation of being, appealing to us that we change our bearing in the world, that we dwell, that we change our life .

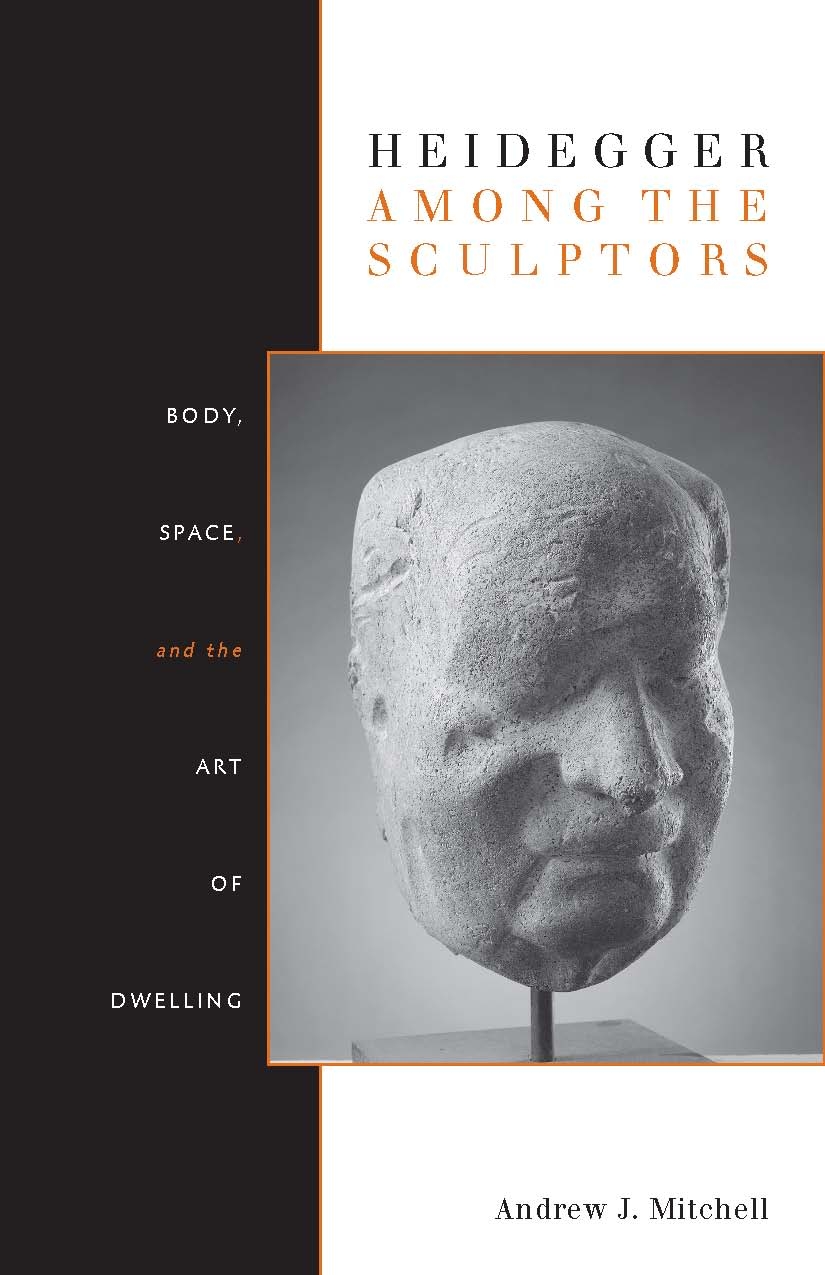

Martin Heidegger, Gnther Neske, Bernhard Heiliger, Max Bill, and Franz Larese at the Erker-Galerie, St. Gallen, Switzerland, for the opening of the Heiliger exhibition, 3 October 1964. Photo courtesy of the Bernhard Heiliger Stiftung.