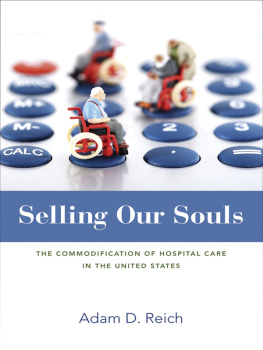

Selling Our Souls

Selling Our Souls

THE COMMODIFICATION OF HOSPITAL CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

Adam D. Reich

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art intune123/123RF

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reich, Adam D. (Adam Dalton), 1981

Selling our souls : the commodification of hospital care in the United States / Adam D. Reich.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16040-5 (hardcover)

1. Hospital care. 2. HospitalsBusiness management. 3. Hospital careCost effectiveness.

I. Title.

RA971.3.R35 2014

362.11dc23

2013034451

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ella

Contents

Selling Our Souls

Introduction

The hospital has a paradoxical place in U.S. society. Such contradictions, between the mission of hospital care and the market for it, are the focus of this book.

The United States is unique among modern industrial nations in the extent to which it has relied on the market to determine the organization and allocation of hospital (and all health care) services. By market I mean, most basically, the principle of exchange for profit or gain. The market has played an important role in the organization of the American hospital since at least the first decades of the twentieth century. Still, over the past forty years, public health concerns, professional autonomy, and charitable impulses have given way even more dramatically to a focus on profit making and the bottom line.

Since all hospitals today must compete for the dollars that accompany patient utilization, all are under pressure to engage in similar practices, such as reducing the amount of free care they provide, investing heavily in capital improvements,

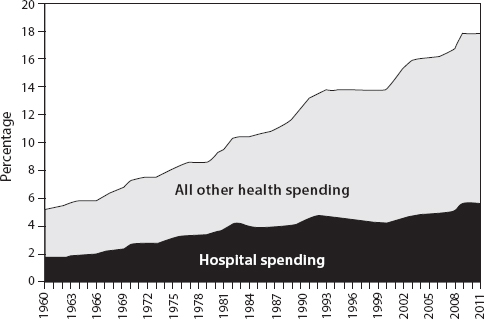

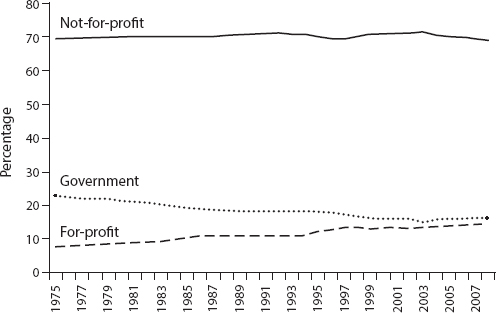

I.1. Health expenditures as percentage of GDP, 19602011.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2012.

Health spending has continued a seemingly inexorable increase as a proportion of gross domestic product, reaching nearly 18 percent in 2010. This rise can be seen both as a cause and a consequence of the ascendance of market actors and market logics across the health care industry.

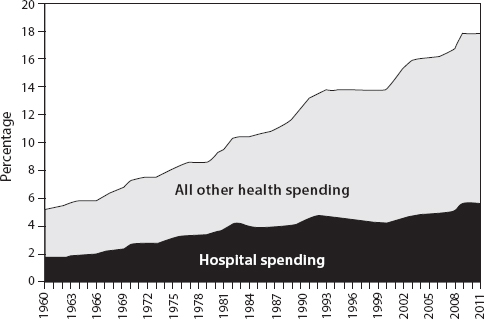

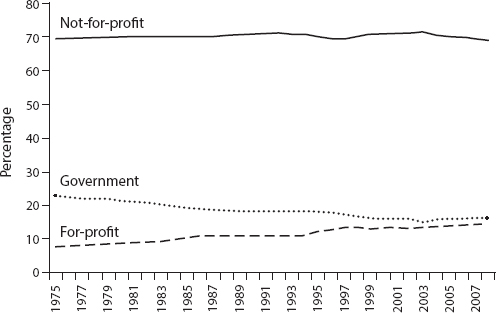

I.2. Percentage of short-term hospital beds by type of control, 19752008.

American Hospital Association, Hospital Statistics.

Market actors wield tremendous power within the hospital industry, but they are not the entire story. Despite market pressures, between 1975 and 2008 the percentage of hospital beds under the control of not-for-profit organizations remained virtually unchanged at around 70 percent (see

Moreover, the development of the hospital market has been mitigated historically by a variety of institutional rules and norms that buffer hospital care from the markets worst excesses. The recently passed Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, intervenes in the market along these lines, changing the broader rules of the game byfor exampleincreasing access to health insurance for the currently uninsured and incentivizing evidence-based medical practice and quality outcomes. (For more about this legislation, see Conclusion in this book.)

So while market forces and market actors have become increasingly important to contemporary hospital practice, the commodification of hospital care in At the same time that hospitals compete in a competitive marketplace, many hospitalsand the people within themwork to sustain social values that sit in uneasy tension with this market.

Welcome to Las Lomas

In order to understand these contradictions, we must look not only at the broad sets of rules and regulations through which the market for hospital care is structured but also at the meanings, practices, and people that make up the hospital itself. This book is a detailed study of three hospitals within the same medium-sized city of Las Lomas. Each hospital was founded in a different era of American medicine to serve a different kind of patient and solve a different sort of problem. Today, these historical legacies frame each hospitals ongoing struggle with a different contradiction in the commodification of hospital care, as each worksimperfectlyto reconcile the social values on which it was founded with the imperatives of the competitive marketplace. (For a detailed discussion of methods, see A Note on Methods in this book.)

Located within a few miles of one another, PubliCare, HolyCare, and GroupCare serve as the only major hospital facilities in the larger 500,000-person county. Each is a part of a different not-for-profit health system (PubliCare previously had been the countys public hospital but was privatized in 1996). Each considers the other two as its primary competitors for the countys pool of insured patients. The three hospitals offer many of the same services, and they face many of the same market pressures. Despite these similarities, however, they are in many ways worlds apart.

Katherine Taylor, a nurse manager at GroupCare, had strong opinions about all three. We spoke together while sitting on flimsy plastic chairs on a small patio just outside GroupCares basement cafeteria. Taylor remembered getting into the nursing profession because of a desire to care for people in difficult times. She had a particular affinity for children, she said, and assumed she would become a pediatric nurse. But this same emotional connection she felt with kids ultimately made pediatrics overwhelming: Because I love them so much [it] was really hard for me, to deal with my emotions around it. And solike many other nurses I would come to meet in the cityTaylor had found ways to manage her emotional vulnerability at work. She realized that she either would have to shut down or would have to find another area of hospital practice. Taylor found the intensive care unit: I have a very fast-working brain, so it was just the constant stimulation: information, machines, critical patients. It kept me on the edge of my seat for the whole twelve hours I was working. So that was really enticing for me. She would escape her vulnerability in the pediatrics ward via the frenetic hum of critical care.

Taylor had been working in Las Lomas for the last fifteen years as a critical care nurse and nurse manager. During this time she had been employed at each of the three hospitals. PubliCare, she thought, was remarkable for the mutual respect among the doctors and the nursing staff there: It was a rare moment at PubliCare that we would have a physician be rude, obnoxious, disrespectfulany of that. But this egalitarianism, she thought, sometimes digressed into a kind of sloppiness: The nurses would sit at the nurses station and laugh at the physicians, talk about things that I was, like, Oh! Ugh! What?! People dressed a little flowerier and funkier than she was used to. And while the care was pretty good, she did not think it was exceptional. No one seemed particularly concerned with national hospital standards: Compliance wasnt really part of what they talked about at PubliCare. Taylor worked her way into a more managerial role at PubliCare and helped oversee an inspection during which the hospital almost lost its accreditation. But she liked the place and loved the people: The people are delightful. Physicians were delightful. It had this great personality, but it really needed to rise up to the level of, you know, clean, competent. The manager before she arrived was a real hippie.

Next page