SPIRALS

MODERNIST LATITUDES

MODERNIST LATITUDES

JESSICA BERMAN AND PAUL SAINT-AMOUR, EDITORS

Modernist Latitudes aims to capture the energy and ferment of modernist studies by continuing to open up the range of forms, locations, temporalities, and theoretical approaches encompassed by the field. The series celebrates the growing latitude (scope for freedom of action or thought) that this broadening affords scholars of modernism, whether they are investigating little-known works or revisiting canonical ones. Modernist Latitudes will pay particular attention to the texts and contexts of those latitudes (Africa, Latin America, Australia, Asia, Southern Europe, and even the rural United States) that have long been misrecognized as ancillary to the canonical modernisms of the global North.

Barry McCrea, In the Company of Strangers: Family and Narrative in Dickens, Conan Doyle, Joyce, and Proust, 2011

Jessica Berman, Modernist Commitments: Ethics, Politics, and Transnational Modernism, 2011

Jennifer Scappettone, Killing the Moonlight: Modernism in Venice, 2014

NICO ISRAEL

THE WHIRLED IMAGE

IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY

LITERATURE AND ART

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52668-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Israel, Nico.

Spirals : the whirled image in twentieth-century literature and art / Nico Israel.

pages cm. (Modernist latitudes)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15302-7 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-52668-5 (e-book)

1. Literature, Modern20th centuryHistory and criticismTheory, etc. 2. Modernism (Literature) 3. Spiralssymbolic aspects. 4. Spirals in art. I. Title.

PN56.M54187 2015

809' .9112dc23

2014028478

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER IMAGE: Waldemar Cordeiro, Idia visvel (Visible Idea), 1956, acrylic on plywood.

COVER AND BOOK DESIGN: Lisa Hamm

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

FOR ESME AND ROMAN

Ihm ist, als ob es tausend Stbe gbe

und hinter tausend Stben keine Welt.

Dann geht ein Bild hinein,

geht durch der Glieder angespannte Stille

und hrt im Herzen auf zu sein.

RAINER MARIE RILKE, DER PANTHER

CONTENTS

FIGURES

PLATES

History decays into images, not into stories.

WALTER BENJAMIN, THE ARCADES PROJECT

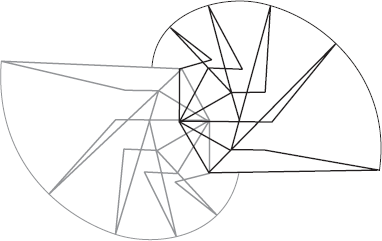

THE SPIRAL AS IMAGE

Spirals have a curious centrality in some of the best-known and most significant twentieth-century literature and visual art. Consider the writings of W. B. Yeats, whose Vision was entranced by a system of widening and narrowing gyres; Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, whose poetry traced Dantesque helical journeys into and out of the modern urban inferno; and James Joyce, whose Ulysses navigated between the Scylla of Aristotelianism and the Charybdis of Platonism, ultimately casting both into the Wake of a thunderous Viconian gyrotundo. Or think, later in the century, of Samuel Becketts obsessive circuitry and abortive spiral journeys or of W. G. Sebald, for whom spiral rings signaled the vertiginous emanations of historical trauma. In the field of visual art, picture the work of Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni, who combined an attraction to speed with a passionate interest in the fourth dimension expressed as bodies in spiraling motion; the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, whose proposal for a spiral monument to the Third International that would outstrip the Eiffel Tower sought to give futurist bravado a rational, leftward spin; and the Franco-American proto-conceptualist Marcel Duchamp, whose Rotoreliefs and Anmic Cinma added a Surrealist idiom of eroticism to a Dadaist attack on the predominance of the optical sense. Or, in postwar art, recall the work of American earthworks creator and filmmaker Robert Smithson, whose Spiral Jetty collided prehistoric past with space-age future, or of South African artist William Kentridge, for whom spiral centers and edges express the inaccessible limits of reconciliation and truth.

Beyond the striking fact that these writers and visual artists draw heavily on spiral forms, what links their diverse projects to one another? Without denying the discursive, generic, and institutional differences between literary and art history, and without arguing, Laocon (or Newer Laocon)-like, for the superiority of one medium over the other, how might we see the spiral as a figure that is common to both fields? What might spirals reveal regarding the shifting assumptions about temporality and spatiality, aesthetics and politics in the twentieth century? How do spirals themselves illuminate processes of reading, of interpretation?

Although the path to be followed in answering these questions is necessarily circuitous, the argument of this book can be stated straightforwardly: spirals are a crucial means through which twentieth-century writers and visual artists think about the twentieth century. Approached as images in the sense Walter Benjamin gives the term, spirals in literature and art illuminate how conceptions of modernity, history, and geopolitics are mutually involved. Embodying tensions between teleology and cyclicality, repetition and difference, locality and globality, spirals challenge familiar modes of organizing disciplines of study. Spirals not only complicate literary and art historys familiar spatiotemporal coordinates (including those based on nation and period), but also offer a way of reconceiving the distribution of the sensible across that century. Put simply, viewed in terms of the spiral, twentieth-century literary and art historyand, indeed, history itselfappear otherwise, are given a different spin.

It is as image in this suddenly springing and flashing sense that I propose to read spirals in twentieth-century literature and art.

In the context of this seminal passage, Benjamin is explicitly elucidating the constellation produced by his own earlier and then-current work. Using another photographic metaphor, Benjamin asserts, just a few notes before the preceding excerpt, that the book on the Baroquethat is, Benjamins own study of the German mourning playexposed the seventeenth century to the light of the present day. Here, in his then-in-progress book on the arcades, something analogous must be done for the nineteenth century, but with greater distinctness (or with more meaning; the phrase in the original is deutlicher).

To be sure, I recognize the pitfalls of launching a century-long study, a duration that runs counter to the current penchant for a narrower, more archival brand of historicism predominant in modernist studies in literature, where books focusing on, say, fifteen- or twenty-year chronological slices are now the norm, or to the still-prevalent tendency in early-twenty-first-century art history to concentrate monographically on individual artists or on chronologically circumscribed movements.