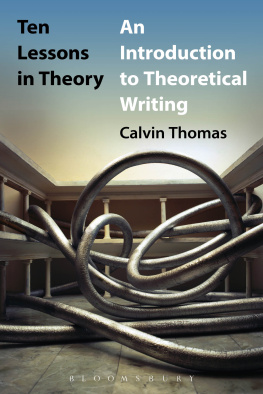

Ten Lessons in Theory

Ten Lessons in Theory

An Introduction to Theoretical Writing

Calvin Thomas

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 175 Fifth Avenue | 50 Bedford Square |

| New York | London |

| NY 10018 | WC1B 3DP |

| USA | UK |

www.bloomsbury.com

First published 2013

Calvin Thomas, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thomas, Calvin, 1956

Ten lessons in theory: an introduction to theoretical writing/Calvin Thomas.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4411-5326-5 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4411-5770-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. English languageRhetoricStudy and teaching.

2. Knowledge, Theory of. 3. CriticismHistory.

4. LiteratureHistory and criticismTheory, etc. I. Title.

PE1403.T46 2013

808.042dc23

2012051555

ePub ISBN: 978-1-6235-6304-2

Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India

For Ihab Hassan

Contents

I would first like to express gratitude to all the students who have been open and kind enough to listen to me for the two decades or so that Ive been teaching these and other lessons in theoretical writing. I would also like to thank Ian Almond, Rahna Carusi, Tim Dean, Lisa Downing, Janet Gabler-Hover, Chris Kocela, John Lowther (for the expert indexing and sharp eye for infelicity), Randy Malamud, Melanie McDougald, Mark Noble, and Matthew Roudan for their support, advice, assistance, and encouragement in the years that I have been planning this book and writing and rewriting these sentences. Special thanks go to Haaris Naqvi, incomparable senior commissioning editor at Continuum/Bloomsbury, for his splendid support of this project, and to my colleague and climbing partner Mark Nunes, who has so often held my life in his hands. And as always, all my thanks and all my love go to Liz Stoehr.

Toward the end of Samuel Becketts novel Molloy , the narrator, who calls himself Jacques Moran, encounters a strange man on a lonely road. Words are somewhat nonsensically exchanged, and violence of some extreme sort apparently ensues. For as Moran rather vaguely reports:

I do not know what happened then. But a little later, perhaps a long time later, I found him stretched on the ground, his head in a pulp. I am sorry I cannot indicate more clearly how this result was obtained, it would have been something worth reading. But it is not at this late stage of my relation that I intend to give way to literature. (1955: 151)

Nor at this early stage of my relation do I intend to linger with this bit of Beckettian pulp fiction. But I would like to note the neat definition of literature that Becketts Moran providesliterature, we are told, is something worth reading.

Toward the beginning of Literary Theory: An Introduction , Terry Eagleton offers a similarly simple definition, a purely formal, empty sort of definition, of the word literaturePerhaps, writes Eagleton, literature means... any kind of writing which for some reason or another somebody values highly (1983/1996: 8). This functionalist definition, as he calls it, doesnt quite satisfy Eagleton, but it works well enough for my purposes here, mainly because it allows meat the outset of this book, Ten Lessons in Theory to begin troubling the definitional distinction between literature and theory, to begin introducing literary theory as a particular kind of writing that for some reason or another more than a few people have valued highly (even if others have loathed and reviled it). Taken together, Eagletons and Becketts definitions of literature give me license to suggest that theory, like literature, is something worth reading, that giving way to literature and falling into theory (Richter 1999) can be intimately related responses to remarkably similar temptations.

Written as a literary introduction to the activities that have come to answer to the nickname theory (Culler 2007: 1), this book stakes itself upon three major premises. The first premise is that a genuinely productive understanding of theoretical activities depends upon a much more sustained encounter with the foundational writings of Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud than any reader is likely to get from the standardized introductions to theory currently available; discourse concerning these four writers thus pervades Ten Lessons in Theory . The second premise involves what Fredric Jameson describes as the conviction that of all the writing called theoretical, [Jacques] Lacans is the richest (2006: 3656); holding to this conviction pretty much throughout, Ten Lessons pays more (and more careful) attention to the richness of Lacans psychoanalytic writings than does any other introduction to theory (that isnt specifically an introduction to Lacan). The books third premise, already introduced above, is that literary theory isnt simply highfalutin speculation about literature, but that theory fundamentally is literature, after allsomething worth reading, a genre of writing that considerable numbers of readers have, for some time now, valued highly, even enjoyed immensely. The book not only argues but attempts to demonstrate that the writing called theoretical is nothing if not a specific type of creative writing, a particular way of engaging with the art of the sentence, the art of making sentences that make trouble sentences that articulate the desire to make radical changes in the very fabric, or fabrication, of social reality. As presented and performed here, theoretical writing involves writing about writing as the very possibility of change (Cixous 1975/2007: 1646).

Both the presentation and the performance of the book are consistent with this emphasis on sentence-making as trouble-making transformation. As its title indicates, the book proceeds in the form of ten lessons, each based on an axiomatic sentence or truth-claim selected from the more or less established canon of theoretical writing. Each lesson works by extensively unpacking its featured sentence, exploring the sentences conditions of possibility and most radical implications, asking what it means to say that the world must be made to mean (Stuart Hall), that meaning is the polite word for pleasure (Adam Philips), that language is by nature fictional (Roland Barthes), and so on. In the course of exploring the conditions and consequences of these sentences, the ten lessons work and play together to articulate the most basic assumptions and motivations supporting theoretical writing, from its earliest stirrings to its most current turbulences. Provided in each lesson is a working glossaryspecific critical keywords (like reification or jouissance ) are boldfaced on their first appearance and defined either in the text or in a footnote.

But while each lesson constitutes a precise explication of the working terms and core tenets of theoretical writing as such, each also attempts to exemplify theory as a practice of creativity (Foucault 1983/1997: 262) in itself. And so, while the book as a whole constitutes a novel approach to theory, it also asks to be approached as a sort of theoretical novel. In other words, Ten Lessons is a textbook, to be sure, but a textbook written to be read closely, not (or so its writer dares to hope) as yet another routine, academically commodified, and dutifully historicized rehearsal of the now-standard theories of literature, and not as a guide to the practical application of theory to literature, but rather as a set of extended pedagogical prose poems or experimental fictions or variations on the theme of theory as literature, of life as literature (Nehamas 1987) and of the world as text (Barthes 1968/1977: 147).

Next page