The Art of

DESCRIPTION

WORLD INTO WORD

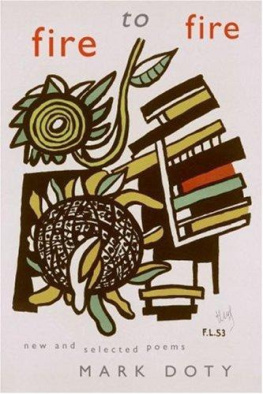

Mark Doty

Graywolf Press

Copyright 2010 by Mark Doty

An Enormous Fish first appeared, in Spanish, in Critica.

Speaking in Figures first appeared in American Poet , the biannual journal of the Academy of American Poets, and was adapted from a lecture Mark Doty gave for the Online Poetry Classroom Summer Institute. Copyright 2007 by The Academy of American Poets. All rights reserved.

This publication is made possible by funding provided in part by a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature, a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and private funders. Significant support has also been provided by Target; the McKnight Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-563-0

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-918-8

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010920769

Cover design: Scott Sorenson

For the Eye altering alters all.

William Blake

We delight in our sensuous involvement with the materials of language, we long to join words to the worldto close the gap between ourselves and thingsand we suffer from doubt and anxiety because of our inability to do so.

Lyn Hejinian

THE ART OF

DESCRIPTION

WORLD INTO WORD

World into Word

It sounds like a simple thing, to say what you see. But try to find words for the shades of a mottled sassafras leaf, or the reflectivity of a bay on an August morning, or the very beginnings of desire stirring in the gaze of someone looking right into your eyes, and it immediately becomes clear that all we see is slippery, nuanced, elusive. As Susan Mitchell says, The world is wily, and doesnt want to be caught.

Perception is simultaneous and layered, and to single out any aspect of it for naming is to turn your attention away from myriad other things, those braiding elements of the sensorium that continuous, complex response to things perpetually delivered by the senses, the encompassing sphere that is such a large part of our subjectivity. The word always makes me think of a label invented to describe the totalizing experience offered by a kind of movie speakers, Sensurround a commercial coinage, but a memorable one, in that it addresses the way were englobed entirely by the reports of our senses, held in a kind of continuous thrall. A seamless weft of informationbut information is the driest and least revealing of essential twenty-first-century words, and the data the senses offer every waking moment is anything but that.

In his memoir Planet of the Blind , Stephen Kuusisto describes a moment in Grand Central Station when he and his guide dog have just gotten themselves lost in the great urban hive of transport. Steve sees a dark, suggestive blur of shapes and colors; I want to write the word only or merely before dark, suggestive blur , but that isnt right. The way he sees is in fact a rich, engaging way of encountering the world, and thats Steves point. His dog is new to the intricate passageways of the station, crowded with ranks of commuters streaming forward at a breathless pace, and Steve could reasonably be terrified. Instead he reports this as an occasion of pleasure, a perceptual adventure; both he and his companion animal are exhilarated, and having, as we say, the time of their lives.

In fact all perception is limited, no matter how acute your eyesight, how sharp the hearing, how sensitive the sense of touch. What we can take in is a partial rendering of the world. To go for a walk with a dog is enough to illustrate this principle. Where a universe of scentshistorical, multifacetedpresents itself to the canine reader, human nostrils detect maybe a little whiff of urine, maybe nothing at all. And dogs, in their turn, seem to be unable to see as we do. Their eyesight is geared to detect motion, the slightest bit of action, but when things are at rest they lack the ability to distinguish colors and patterns that human eyes might. Deer cannot see red or orange, a biologist writes, but apparently can see blue much better than we can. Who can even imagine what that would mean, for blue to bewell, more?

All accounts, it seems, are partial; thus all perception might be said to be tentative, an opportunity for interpretation, a guessing game.

On a warm August evening on a pier in Cherry Grove, New York, I watched a display of fireworks. The wooden dock was crowded, everyone excited for the show to start. Police boats and fire boats whizzed around on the water. When the first flare went up, it became clear that the barge from which the rockets flared was anchored a mere hundred yards off the end of the pier. We could see, in a way I never really did before, the rough industrial-looking process of firework-shooting. When a group of streaks all went up at once, the metal barge itself was lit, and you could smell the gunpowder, and see the fire fountains sputtering into action.

Proximity to the source meant that the shells were exploding right over our heads. A few children had to be comforted, a few shocked pets hurried away, but everyone else loved it, craning their heads back and taking in the gold and green and fuchsia sparks exploding over us in the form of starbursts or fantastic down-raining flowers.

Here I sigh. That last sentence just doesnt come anywhere close to evoking the actual visual or auditory experience. Not to mention the smell of burnt powder and drifting smoke picking up a little salt and seaweed tang, mingling with the annoying cigarette of the man next to me. Or my awareness that the colors overhead were complicated by a peripheral sense that the intense light of the launching rockets had lit up the water a peculiar army-surplus green, while a cheerful little blue and yellow inflatable skiff to our right rocked on the wavelets beneath all that celestial action.