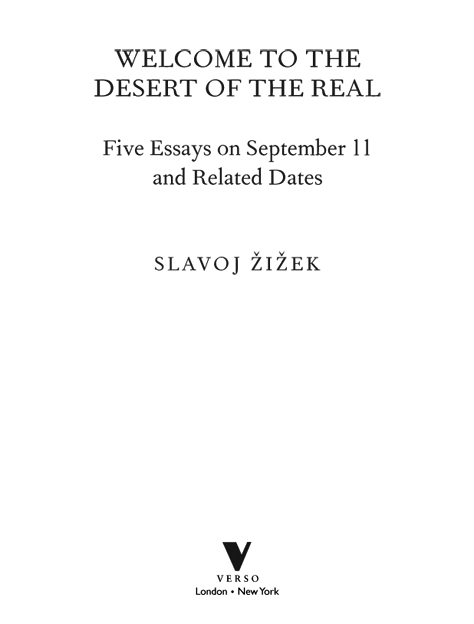

Published by Verso 2012

Slavoj iek 2012

First published by Verso 2002

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-019-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-031-5 (US)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-005-0 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

To Pamela Pascoe and Eric Santner, without any doubt!

Contents

Introduction: The Missing Ink

In an old joke from the defunct German Democratic Republic, a German worker gets a job in Siberia; aware of how all mail will be read by the censors, he tells his friends: Lets establish a code: if a letter you get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, its true; if its written in red ink, its false. After a month, his friends get the first letter, written in blue ink: Everything is wonderful here: the shops are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, cinemas show films from the West, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair the only thing you cant get is red ink. The structure here is more refined than it might appear: although the worker is unable to signal that what he is saying is a lie in the prearranged way, he none the less succeeds in getting his message across how? By inscribing the very reference to the code into the encoded message, as one of its elements. Of course, this is the standard problem of self-reference: since the letter is written in blue, is its entire content therefore not true? The answer is that the very fact that the lack of red ink is mentioned signals that it should have been written in red ink. The nice point is that this mention of the lack of red ink produces the effect of truth independently of its own literal truth: even if red ink really was available, the lie that it is unavailable is the only way to get the true message across in this specific condition of censorship.

Is this not the matrix of an efficient critique of ideology not only in totalitarian conditions of censorship but, perhaps even more, in the more refined conditions of liberal censorship? One starts by agreeing that one has all the freedoms one wants then one merely adds that the only thing missing is the red ink: we feel free because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom. What this lack of red ink means is that, today, all the main terms we use to designate the present conflict war on terrorism, democracy and freedom, human rights, and so on are false terms, mystifying our perception of the situation instead of allowing us to think it. In this precise sense, our freedoms themselves serve to mask and sustain our deeper unfreedom. A hundred years ago, in his emphasis on the acceptance of some fixed dogma as the condition of (demanding) actual freedom, Gilbert Keith Chesterton perspicuously detected the antidemocratic potential of the very principle of freedom of thought:

We may say broadly that free thought is the best of all safeguards against freedom. Managed in a modern style, the emancipation of the slaves mind is the best way of preventing the emancipation of the slave.

Is this not emphatically true of our postmodern time, with its freedom to deconstruct, doubt, distantiate oneself? We should not forget that Chesterton makes exactly the same claim as Kant in his What is Enlightenment?: Think as much as you like, and as freely as you like, just obey! The only difference is that Chesterton is more specific, and spells out the implicit paradox beneath the Kantian reasoning: not only does freedom of thought not undermine actual social servitude, it positively sustains it. The old motto Dont think, obey! to which Kant reacts is counterproductive: it effectively breeds rebellion; the only way to secure social servitude is through freedom of thought. Chesterton is also logical enough to assert the obverse of Kants motto: the struggle for freedom needs a reference to some unquestionable dogma.

In a classic line from a Hollywood screwball comedy, the girl asks her boyfriend: Do you want to marry me? No! Stop dodging the issue! Give me a straight answer! In a way, the underlying logic is correct: the only acceptable straight answer for the girl is Yes!, so anything else, including a straight No!, counts as evasion. This underlying logic, of course, is again that of the forced choice: youre free to decide, on condition that you make the right choice. Would not a priest rely on the same paradox in a dispute with a sceptical layman? Do you believe in God? No. Stop dodging the issue! Give me a straight answer! Again, in the opinion of the priest, the only straight answer is to assert ones belief in God: far from standing for a clear symmetrical stance, the atheists denial of belief is an attempt to dodge the issue of the divine encounter. And is it not the same today with the choice democracy or fundamentalism? Is it not that, within the terms of this choice, it is simply not possible to choose fundamentalism? What is problematic in the way the ruling ideology imposes this choice on us is not fundamentalism but, rather, democracy itself: as if the only alternative to fundamentalism is the political system of liberal parliamentary democracy.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxy, San Francisco: Ignatius Press 1995, p. 114.

1 Passions of the Real, Passions of Semblance

When Brecht, on the way from his home to his theatre in July 1953, passed the column of Soviet tanks rolling towards the Stalinallee to crush the workers rebellion, he waved at them and wrote in his diary later that day that, at that moment, he (never a party member) was tempted for the first time in his life to join the Communist Party. It was not that Brecht tolerated the cruelty of the struggle in the hope that it would bring a prosperous future: the harshness of the violence as such was perceived and endorsed as a sign of authenticity. Is this not an exemplary case of what Alain Badiou has identified as the key feature of the twentieth century: the passion for the Real [la passion du rel]?price to be paid for peeling off the deceptive layers of reality.

In the trenches of World War I, Ernst Jnger was already celebrating face-to-face combat as the authentic intersubjective encounter: authenticity resides in the act of violent transgression, from the Lacanian Real the Thing Antigone confronts when she violates the order of the City to the Bataillean excess. In the domain of sexuality itself, the icon of this passion for the real is Oshimas Empire of the Senses, a Japanese cult movie from the 1970s in which the couples love relationship is radicalized into mutual torture until death. Is not the ultimate figure of the passion for the Real the option we get on hardcore websites to observe the inside of a vagina from the vantage point of a tiny camera at the top of the penetrating dildo? At this extreme point, a shift occurs: when we get too close to the desired object, erotic fascination turns into disgust at the Real of the bare flesh.