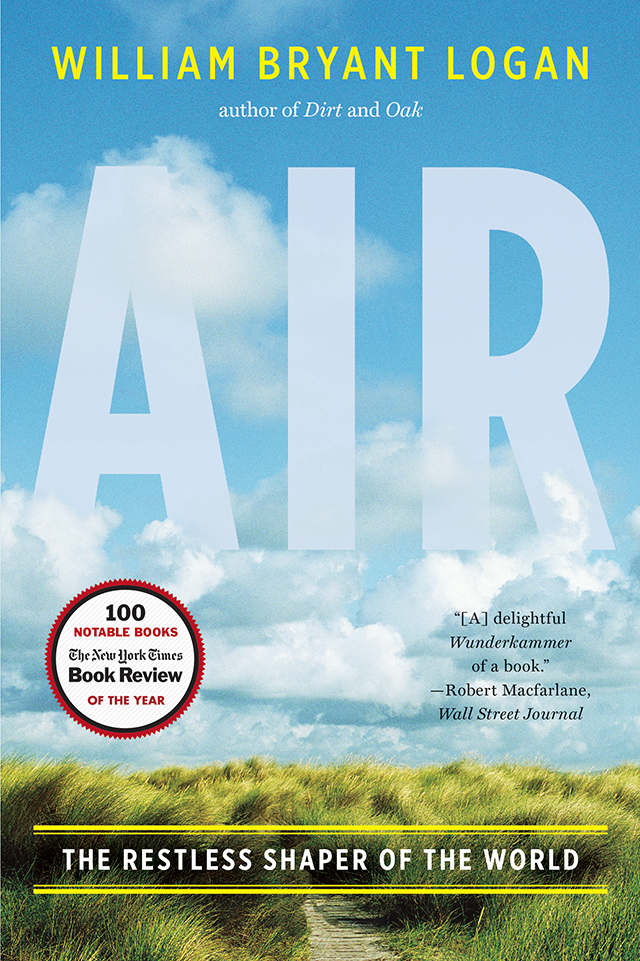

ALSO BY WILLIAM BRYANT LOGAN

Oak: The Frame of Civilization

Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth

For Sam, Jacob, Eliza, and their grandmother Jean

Contents

Acknowledgments

So many people gave me their generous help in the research and preparation of this book. I am deeply grateful to them all.

Special thanks are owed to John Haines and Joe Witte. The former, who is the retired New York State Mycologist and appears twice in Air , was wonderfully generous with his time and his knowledge. The spore sucker was his invention. It was delightful to work with him in what Mary Banning would have called the debatable world of the fleshy fungi. Meteorologist Joe Witte both inspired me with his knowledge and his images and resources, and helped me to find numerous people in the world of weather forecasting who were crucial to the book.

Among the National Weather Service forecasters who were tremendously helpful were Brandon Smith of the Upton, New York, station and Steve DeRienzo, Kimberly McMahon, and science officer Warren Snyder, of the Albany, New York station. They helped me not only on the specific sections in which they are mentioned but also offered many useful comments about the predictability of the weather in general.

Atmospheric scientist Kerry Emanuel helped me a great deal, both in the understanding of general weather phenomena and in the realm of weather forecasting. He also provided memories and comments regarding the work of Edward Lorenz. Howard Bluestein, of the University of Oklahoma, patiently explained to me his work on tornado genesis and also helped to elucidate the character of Edward Lorenz.

The climate scientists Gavin Schmidt and Kostas Trisgaridis of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies were both amazingly forthcoming in helping me to understand the roles of aerosols in a changing climate and the way in which climate models are generated and used.

A special word of thanks is due my sister-in-law Maud Humphrey, late administrator of the Art Department at the University of Kansas, who put me in touch with Professor Sally Cornelison. The professor found a reference that helped me solve questions about Bellinis iconography.

Dr. Jesse Roman and Dr. Robert Powell, both prominent pulmonologists in Louisville, Kentucky, helped me to understand respiratory disease as it relates to both indoor and outdoor air pollution. I met both men at the wonderful Sacred Air Festival, organized as the latest in their annual Festivals of Faiths, by Christy and Owsley Brown.

University of Washington astronomer Donald Brownleean important contributor to my favorite book, Global Biogeochemical Systems helped me understand the different atmospheres on Earth, Venus, and Mars.

Kari Castle and Wayne and Paula Sanger made me understand their passion for hang gliding. It was a pleasure to listen to them and to watch the Sangers and their South African friend Adrian fly.

David Oguss and Captain Richard Sianoboth pilots of deep experience and humanitytrain working pilots using simulators and classroom training. Oguss put me through the paces of a flight simulator for a private jet, and both men talked with me at length about their experiences as teachers and pilots.

I also owe thanks not only for the expertise but also for the patience of my flying instructor, Brian Monga, of Air Fleet Training. He was always cheerful and helpful.

Chad Jemison and everyone at the Edmund Niles Huyck Preserve in upstate New York were so helpful in providing me access to all the information they had about creatures living on the preserve.

As always, the New York Public Library was an invaluable resource for my research. I am grateful for my space in the Wertheim Study, and in particular to librarian Jay Barksdale.

It was a very great pleasure to work with my editor, Alane Salierno Mason, whose sensitive, intelligent editing and questions have become an important part of my writing process. Her assistant, Denise Scarfi, patiently fielded endless questions about illustrations, forms, and deadlines with grace and good humor, despite my tardiness and occasional hysteria.

So many friends have helped me with their reflections both directly and indirectly on the subject matter of this book. I want to thank especially Steven OConnor, whose thoughts always inspire and challenge me, and David Sassoon, whose conversation and climate blog are very important to me. I also want to thank three priests whom I have been lucky enough to know. The Very Reverend James Parks Morton has been a source of inspiration to me for more than two decades. The Reverend Ray Donohue delights me with his broad knowledge, his concise and illuminating sermons, and his deep humanity. Father Mark Lane is warm and generous, and his intelligence always hits the nail on the head.

Finally, I owe a great debt to my wife, Nora H. Logan, for her fine illustrations. It is lovely to see her enlivening work with pen and ink. In addition, she was a constant source of controversy and inspiration as I tried to talk with her about what I was writing. And many thanks to my daughter, Eliza Logan, who on short notice managed to track down and get permission for all the photographs in Air .

I have certainly neglected to mention at least a few people, and I will be kicking myself about it. I ask them to forgive my addled pate.

For the use I have made of what others were generous enough to tell me, I alone am responsible.

we are bound

Like anything to everything around.

Edwin Denby

Introduction

At 3:30 p.m. on September 16, 2010, Brandon Smith left home, bound for his shift at the Upton office of the National Weather Service. At about 4:00 p.m., Aline and Billy Levakis climbed into their Lexus and left their home, going to visit relatives. At 4:30 p.m., I was working at my desk in downtown Brooklyn and getting ready to walk the dog. I was right in the middle of something difficult, so I put off the walk until later.

Smith arrived at the station, an unprepossessing beige cookie-cutter building on the sprawling, pine-barren grounds of Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island. The building is wedged into a cut-out space in a pine forest, but it would fit as well into a mall. It has few windows, and these are high above the heads of those working inside. The old joke about weather forecasters not looking out the window, then, is at least half true. You can look out the window all right, but all you can see are pine branches or sky. Still, the weather forecasters do not want for data.

Forecasters at Upton sit in front of a three-headed workstation. Three large flat-panel monitors face them, at center and to the left and right. Each of these screens can be divided into four segments. With a few keystrokes, the forecasters can call up any of dozens of models that predict what the weather might be. They can also call up any and all data from weather satellites, not to mention Uptons own radar or the radar from Newark, LaGuardia, or Kennedy airport. Since the airport radars refresh every minute, while the in-house radar updates information only every seven minutes, they get not only different pictures of the air but also fresher ones. They can also call up any other data, including the results of weather balloon launches anywhere in the world, and the reports from aircraft and ships at sea.

On September 16, Smith was to go on duty at 4:00 p.m. It was a humid day in early autumn, with the temperature in the high 70s. He knew there might be afternoon thunderstorms, but nothing big was on the horizon. The off-going shift of forecasters briefed the incoming shift on what they had been seeing. Out west in Pennsylvania they saw what might be the beginning of big thunderstorms. One forecaster said that he had detected possible rotation in one of them.

Next page