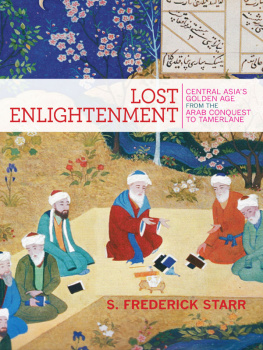

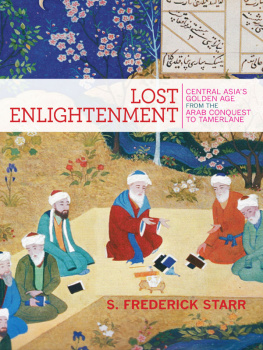

Lost

Enlightenment

Lost

Enlightenment

CENTRAL ASIAS GOLDEN AGE

FROM THE

ARAB CONQUEST TO TAMERLANE

S. Frederick Starr

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Detail of ms. Elliott 339, fol. 95v, courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Starr, S. Frederick.

Lost enlightenment : Central Asias golden age from the Arab conquest to Tamerlane / S. Frederick Starr.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15773-3 (hardcover)

1. Asia, CentralHistoryTo 1500. I. Title.

DS288.3.S73 2013

958.02dc23

2013013684

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro text with Archer display

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To strive for knowledge is the duty of every Muslim.

Saying or Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad,

recorded in the tenth century by the scholar

Abu Isa Muhammad Tirmidhi (824892)

from Tirmidh (Termez), and inscribed at the

entrance to the madrasa of Ulughbeg, ruler and

astronomer, Samarkand, ca 1420

Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom.

And with all thy getting, get understanding.

Bible, Proverbs 4.7, King James Version

Contents

Illustrations

M APS

P LATES

Following page 292

F IGURES

Preface

This book was written not because I knew the answers to the questions it poses, or even because I had any particular knowledge of the many subjects and fields it touches upon, but because I myself wanted to read such a book. It is a book I would have preferred someone else to have written so I could enjoy reading it without the work of authorship. But no one else took up the assignment. Central Asia as yet has no chronicler comparable to Joseph Needham, the great historian from Clare College, Cambridge, whose magisterial, twenty-seven-volume Science and Civilization in China has no equal for any other people or world region. And so I backed into the task, in the hope that my work might inspire some future Needham from the region or from among scholars abroad.

The questions raised in this book became my constant companions for nearly two decades and over several scores of trips through every corner of the regiontrips that included scorching treks in the Karakum Desert of Turkmenistan and being snowbound for nearly a week in the Pamirs at minus 40 degrees. Enormous, predigital piles of notes made entrance to my office a challenge that few chose to face. Now, with the volume done, I find myself saying, with Edward Gibbon in the preface to his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, that I have ventured, perhaps too hastily, to commit to the press a work which in every sense of the word deserves the epithet of imperfect. And, by the way, I know all too well that I am no Gibbon.

It would be more than a stretch to say that I am qualified to have undertaken this book. But at least I can claim a long-term interest in the subject. The Persian world first opened to me when, at age eighteen, I met my freshman roommate at Yale, Hooshang Nasr, whose father was mayor of Tehran under the shah. Hoosh went on to become a dedicated medical doctor who loyally served his country. My first contact with the Turkic world began through archaeological work at Gordium in Turkey, where Alexander the Great cut the Gordian knot, and eventually extended over several seasons spent mapping ancient roads in Anatolia. Neither of these links qualified me as an expert on anything, but from these early contacts to the present it has been natural for me to view both the Persian and the Turkish worlds as places inhabited by exceptionally interesting people, among whom are many good friends of mine.

The number of scholars and experts who have plowed the separate furrows of this book is staggering. It is fashionable in some quarters to fault Western and Russian scholars of the past two centuries for their orientalism. But without their painstaking research, the larger story of the intellectual effervescence of the Islamic East would never have become known to the world. This has been a thoroughly an international effort. Among the many participants are French savants like Jean Pierre Abel-Remusat, Farid Jabre, tienne de la Vaissire, and Frantz Grenet, not to mention the many authors of the publications, since 1922, of the Dlgation archologique franaise en Afghanistan. In Germany Heinrich Suter, Adam Mez, and others founded a tradition that continues today in the likes of Josef van Ess, Gotthard Strohmaier, and a host of younger scholars from both the former East and West, while the Czech Republic claims the great literary scholar Jan Ripka.

Across the English Channel, adventurers Armenius Vambery and Sir Aurel Stein, both of them immigrants from Hungary, sparked the imagination of the English-speaking world and of all Europe with the accounts of their explorations in Greater Central Asia. Then came linguists like Edward Granville Browne and translator Edward Fitzgerald, who together did much to bring the treasures of regional literature to broader notice. In the twentieth century the awesomely prolific Clifford Edmund Bosworth from Manchester wrote with insight on scores of topics essential to a book like this, while Georgina Herrmann and her colleagues extended this tradition into archaeology. Patricia Crone and other British scholars have advanced the study of many philosophers from the region, while E. S. Kennedy did authoritative work on the scientists. American scholars should also be noted, especially Richard N. Frye and Richard W. Bulliet, whose research on Nishapur, Bukhara, and the broader region inspired a generation of historians. Such gifted linguists and translators as Robert Dankoff and Dick Davis have opened windows on unknown or underappreciated masterpieces. Dimitri Gutas and other distinguished scholars have analyzed the writings of Farabi and other Central Asian thinkers who wrote in Arabic. Raphael Pumpelly and Fredrik Hiebert should also be saluted for their pioneering archaeological research that traced the first grain for bread to a site in what is now Turkmenistan. In addition to all these, a host of younger scholars, especially in Europe and the United States, are on the lip of transforming our understanding of the region and time.

Iranian scholarship also continues to make important contributions. Tehran scholars have undertaken the monumental task of locating, editing, and publishing the complete works of Ibn Sina and several other major thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. They are also conducting important research on the various traditions of Sufism. Persian scholarship also thrives in emigration, where it has given rise to such valuable productions as the New York-based

Next page