Contents

The information and advice presented in this book are not meant to supersede or substitute for the expertise of a personal physician. Consult a health care professional before acting on any of the information presented or implied in these pages.

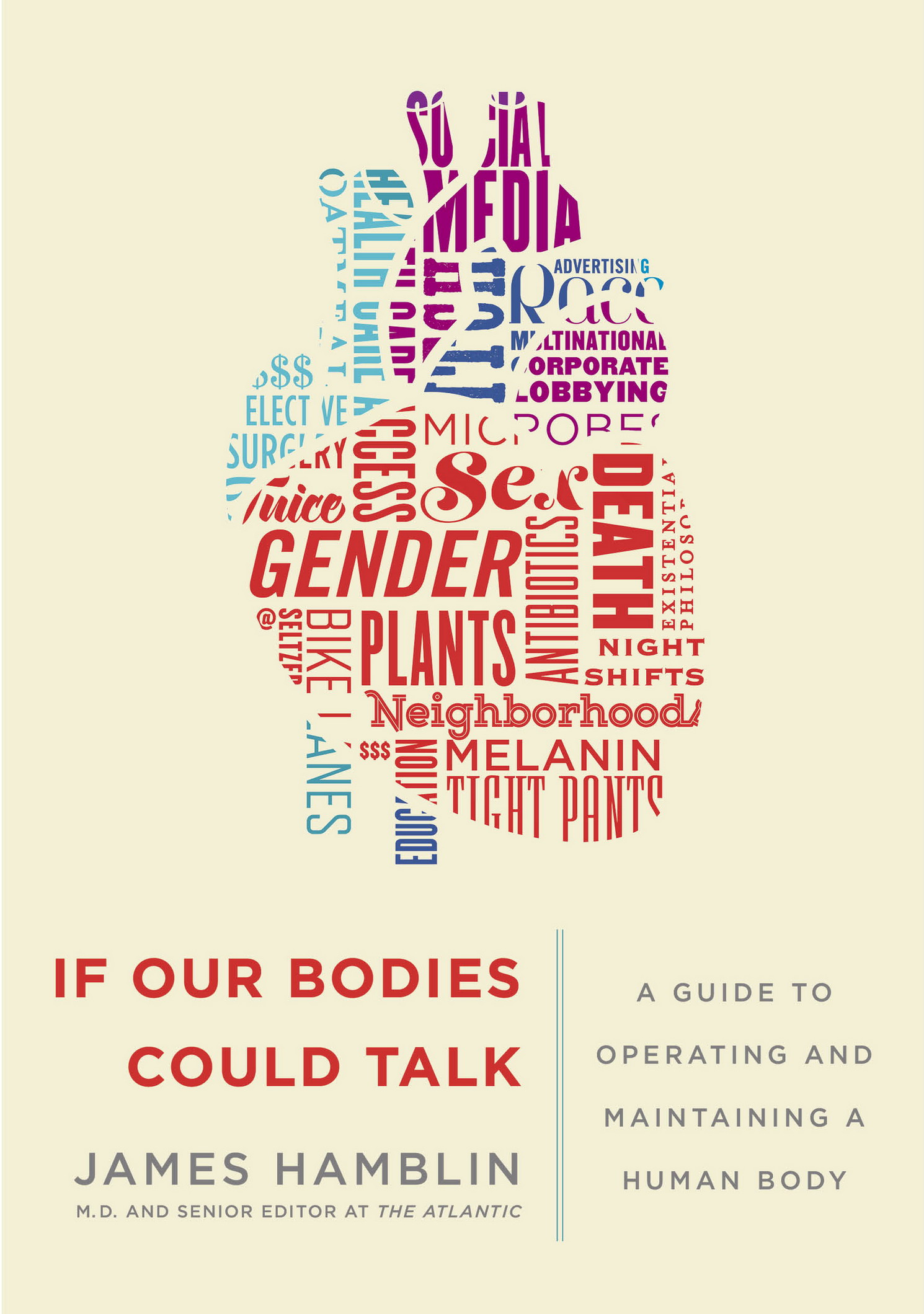

Copyright 2016 by James Hamblin

Illustrations copyright 2016 by Hallie Bateman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Cover image: heart shape, gst/Shutterstock

Cover design by John Fontana

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hamblin, James, author.

Title: If our bodies could talk : a guide to operating and maintaining a human body / James Hamblin, M.D.

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016046694 | ISBN 9780385540971 (hardback) | ISBN 9780385540988 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: HealthPopular works. | HealthMiscellanea. | BISAC: HEALTH & FITNESS / Healthy Living. | SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Human Anatomy & Physiology. | HEALTH & FITNESS / Reference.

Classification: LCC RA776.H183 2016 | DDC 613dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016046694

Ebook ISBN9780385540988

v4.1

a

To Sarah Yager, John Gould, and the rest of The Atlantic

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

M y medical school roommate became an ophthalmologist and moved to Texas. He encouraged me to address here the most common question that people ask him in conversation when they learn his occupation:

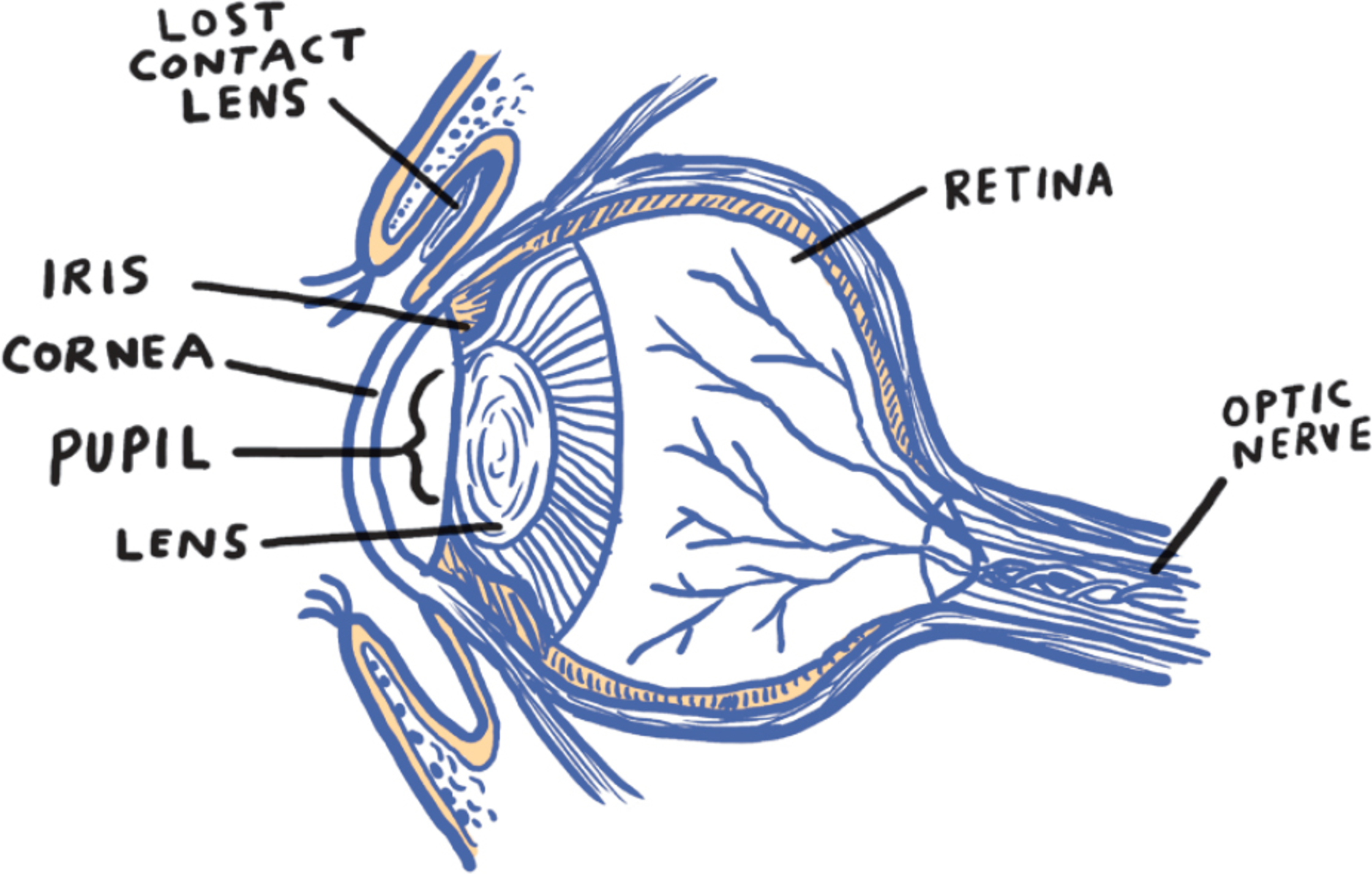

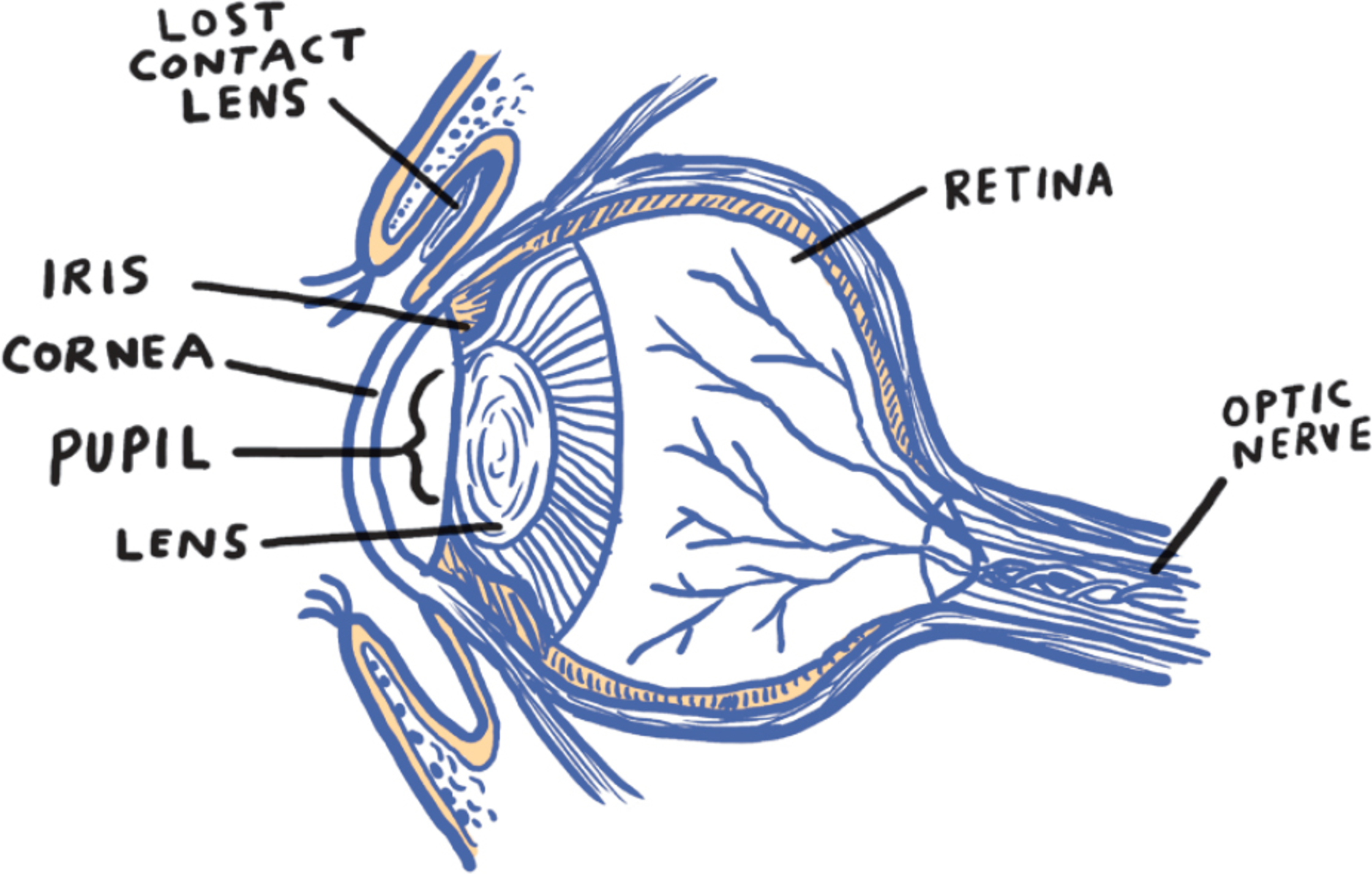

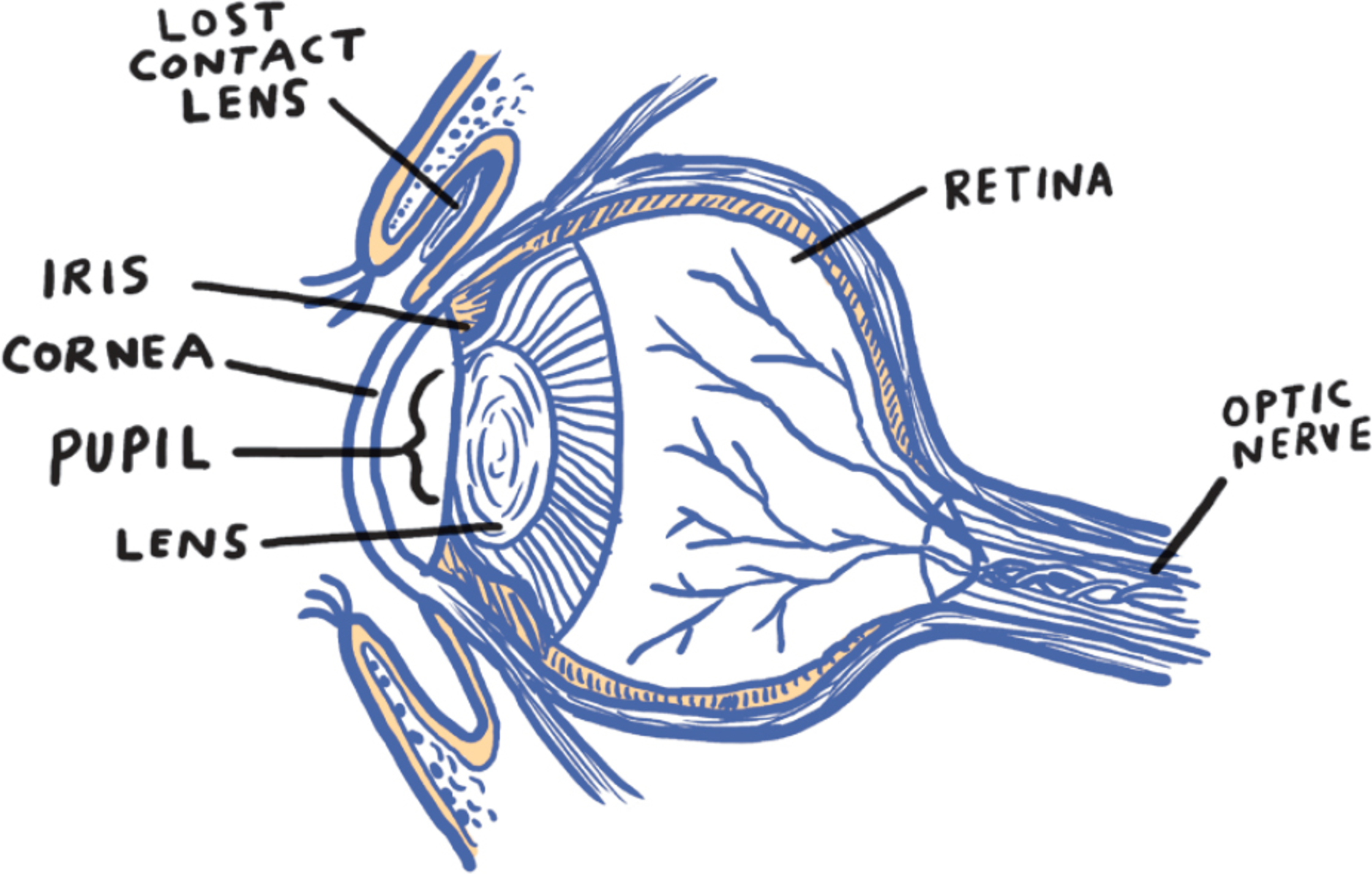

If I lose a contact lens in my eye, can it get into my brain?

I laughed. He didnt. The question has lost its humor to him.

There are common, debilitating eye diseases that people could be asking him aboutlike macular degeneration, or night blindness, or glaucoma, which will affect 112 million people by 2040, leaving many without sight.

That last one resonates with me because I have it. The pressure inside my eyeball is higher than it should be. My eye wont explodethough that image does absurdly haunt me. The decline in most glaucoma is, rather, insidious. Im told I wont even notice as my eyes faila term that doctors use commonly, unthinkingly, until were the ones whose parts are failing. Its more accurately the case that the pressure inside my eyes will gradually damage the dense focus of nerves in the retina at the back of my eye. I stand to slowly lose vision at the peripheries of my field of view, and then entirely.

This wont happen for years.

Which is all to say that we have our reasons for concerns about our eyes and other parts. Every one is valid. Sometimes it helps to put them in the context of other peoples problemsof how bad things could be. But sometimes it doesnt. So, to the question at hand: The space under our eyelids does not connect to our brains. Its a cul-de-sac that ends about halfway over our eyes. Our brains are safe from contact lenses.

This anatomy is something you might have seen if you were among the forty million people who experienced the most popular traveling museum exhibition of all time: Body Worlds. Though you may have missed the cross sections of human heads if you were too distracted by the corpses that were posed having sex. That element of the exhibition shocked many attendees, as did rumors about dubious procurement of the bodies. Maybe most shocked was the art world, though, by the very fact of the enormous and enduring popularity of an exhibit that might have been alternatively titled Actual Corpses.

Of all the art bestowed to us throughout history, why should what is essentially a glorified biology lab be so successful and adored? Especially as most of us are otherwise so averse to discussing so much of what our bodies do, and considering death, in any realistic way?

Body Worlds is the brainchild of the German anatomist Gunther von Hagens, who invented the plastination process that allows bodies to be preserved without decomposing. While most exhibits come and go, Body Worlds has now been appearing around the world for more than two uninterrupted decades. It even stays open on Friday nights to accommodate couples who want to make a date of it.

The marketing professor Kent Drummond at the University of Wyoming surmises that Body Worlds speaks to people because it manages to juxtapose our distaste for the abject with our desire to live forever. The displays draw on the sublimity of our mortality without leaving us feeling consumed by it. Drummond came to this understanding by studying not only the corpses but also living people as they move through the exhibition. He writes in a field note, In one oft-repeated pattern of interaction, a man points to a body part in a casement, then explains to a woman how that part functions. He does so by showing her where it is on his body.

This masculine exhibitionism may be more sobering than the corpses themselves. Its also in keeping with the grand vision of Von Hagens, who identifies as a medical socialist. He believes that health information should be a social good: the constellation of factors that go into picking up a cigarette should include an abiding familiarity with a black, necrotic, emphysematous lung, which should not be exiled to textbooks and morgues. Inside Body Worlds, we can clearly see and contemplate our organs and their mortality, if only for one date night. Placards scattered throughout the exhibition urge self-reflection, such as Kahlil Gibrans Your body is the harp of your soul.

I dont think that means anything, but Von Hagenss philosophy does. Democratizing health information has become the norm well outside the walls of his exhibit. A past world in which doctors were the keepers of all medical knowledgewhose job was primarily dispensing directivesis gone. Most of us are rather awash in information nowso much so that it can be difficult to know what to make of it.

Googling bodily concerns isnt always helpful. Anonymous people in forums can be found debating all thingsincluding the great dilemma of the contact lens. (Can it get far into my eye to my brain and cause damage? What if it goes down my spine and into my shoe? Is it still safe to wear again?) And even when you find a reliable-looking source of health information, there is almost always a ready conspiracy theorist who writes with passion and anecdotal logic to warn everyone not to trust that source. Usually its a guy on Reddit named Gene. Gene personally lost five hundred contacts in his brain, and he had to have them surgically removed. He has the mass of desiccated contact lenses sitting in a jar on his desk.