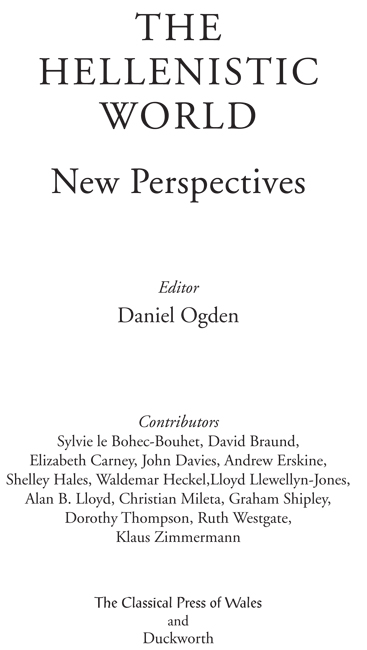

The papers collected here proceed from a colloquium organized by the University of Wales Institute of Classics and Ancient History (UWICAH) at Hay-on-Wye, July 1719, 2000. The volume is dedicated to our former colleague, Stephen Mitchell, the co-founder of UWICAH, in celebration of his appointment to the Leverhulme Chair of Hellenistic History at the University of Exeter, and in thanks for his guidance with the project.

INTRODUCTION

FROM CHAOS TO CLEOPATRA

Daniel Ogden

The hellenistic world, the Greek-dominated world between 323 and 30 BC, is less often regarded as a field of ancient history than as an absence within it. Publishers fear the very word hellenistic for its supposed obscurity and go to extraordinary lengths to banish it from the main titles of their books. The conventional expedient is the framing or book-ends approach, that is, to define the period by its edges, or even in terms of individuals or events that are actually exterior to it in time or culture. The ancient-history publishers best boy, the ever-bankable Alexander, is repeatedly pressed into service to constitute the first book-end, for all that he falls outside the period by definition, since it is his death that marks its commencement. A host of conveniently A-alliterative terms contend to join him as the second book-end: Alexander to Actium; Athens from Alexander to Antony ; From Alexander to Augustus.

But the term hellenistic, which retains full popularity between covers, is itself problematic as a description of the period and civilization under discussion. It is a modern derivative of the ancient verb hellniz, Greek-ize, which is used in Maccabees to denote the acquisition of Greek language and lifestyle by Jews.

Introductions to general works and article-collections on the hellenistic period typically tell us that it has long languished in neglect, and here is our third absence. More specifically, they tell us that this period of neglect has recently come to an end, with work on the subject only now at last burgeoning. This is fortunate: heaven forfend that scholars should find themselves publishing in an unfashionable area. One could be forgiven for, in innocence, taking such claims in the recent literature at face value. It at once becomes apparent that such a claim does not describe any objective reality in the practice of ancient studies. Rather, it is revealed as a rhetorical decency, as a commonplace without which no preface to hellenistic material can be complete, and as, first and foremost, a myth. The study of the hellenistic world is forever, it seems, newly arriving, adventitious, like the god Dionysus.

In recent years a new variety of absence has been devised for the hellenistic world, as scholars have attempted to dismantle its boundaries in time and space. It is now customary to promote the elements of continuity the hellenistic world shared with the classical one that preceded it and the imperial one that succeeded it.

The time has come, surely, to reassert an honest definition of the hellenistic world in plain language. The hellenistic world is very easy indeed to define in terms of its single most important constituent,

Did the later ancients themselves perceive the hellenistic period as a coherent entity?

30 BC was probably perceived as an even stronger and more decisive watershed. We can not be reminded too often of the last words Plutarch gave to Cleopatras handmaiden Charmion, after she had helped the queen kill herself, words which were so memorably reworked in the closing lines of Antony and Cleopatra:

Someone said in anger, This is no fine thing, is it, Charmion? She replied, Nay rather, it is the finest, and befits the scion of so many kings.

Plutarch, Antony 85

FIRST GUARD: What work is here! Charmian, is this well done?

CHARMIAN: It is well done, and fitting for a princess descended of so many royal kings.

Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, Act 5, Scene 2

So many kings: how many? All the Ptolemies, of course, but the earlier Seleucids were also Cleopatras ascendants, and these are hardly excluded. Nor are the Argeads. Even if nothing was made of the possibly real, albeit indirect, connection to the Argead family through Ptolemy of Alorus, Ptolemy Soter, the dynastys founder, had put it about that he was the secret son of Philip II. Nor are the pharaohs excluded. Even if Cleopatra did not draw down the blood of Egyptian royalty through her (to us) mysterious mother and grandmother, the notion that Alexander himself had been secretly sired by the last pharaoh Nectanebo II had at any rate conferred upon Soter a pharaonic brother, of sorts. This concise and powerful epitaph, then, encapsulates in the noble death of a single woman not only the end of her immediate dynasty but also that of the history of the world, which the Greeks knew to have begun, long before their own, with the pharaohs. Such a view of the significance of Cleopatras death is expressed in more explicit and extreme terms by Lucian, who speaks of the duties of the pantomime-dancer,

His entire stock-in-trade is ancient history, the capacity to call episodes to mind readily and to represent them with appropriate dignity. For, beginning right from Chaos and the moment when the universe was created, he must know everything down to the tale of the Egyptian Cleopatra.

Lucian, On Dancing 37

Here the death of Cleopatra brings a close to everything that had ever happened before it. The death of Alexander was not the only lower time-limit canonized in the Second Sophistic.

In the search for ancient periodizations we may be tempted to turn to the chronological frames constructed by ancient historiography. Admittedly, there do not seem to have been a great many ancient prototypes for the histories scholars now produce of the hellenistic period, that is to say, histories with a focus roughly commensurate with the 32330 bc span and with the geographical spread of Greek culture during it. But then, according to comparable criteria, there were no ancient prototypes for our histories of the archaic or classical periods either. Antiquitys histories tended to be either wider (universal) in scope, or much narrower in their temporal and geographical purview. But one lost history, about which we are frustratingly under-informed, is indeed thought to have focused tightly on the hellenistic world, and in particular upon its four great dynasties. Timagenes of