This book tells the story of New Zealands frogs, reptiles, birds and mammals from their origins in the Cretaceous era to the much-altered fauna of the present day. The first three chapters set the scene so the story can unfold. Chapter 1 traces the origins of the New Zealand land mass and its vertebrate animals (excluding fishes, the only vertebrate group beyond the scope of this book). Chapters 2 and 3 examine the biogeography of the countrys frogs, reptiles, non-marine birds and bats, and the ecological factors that are important to understand the changes that have taken place since people first visited then settled New Zealand. Chapter 4 describes the vertebrate communities in forest and wetland habitats during the last two and a half million years the Pleistocene and Holocene eras up to the point when, about 2000 years ago, humans apparently visited and left their rats.

Next I look at the effects that humans and introduced animals have had on the communities described in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 reviews the extinctions that have occurred, and Chapter 6 examines the vertebrate animals introduced to New Zealand since European contact. The forest vertebrate communities present today are described in Chapter 7. I discuss the ecology and conservation of marine birds and mammals in Chapter 8. During the last 50 years there have been many often heroic attempts made to save those species now endangered. In Chapter 9 I review the efforts that have been made to conserve what remains of this once- distinctive , now-tattered biota and the ways that conservation management has changed over that period. Finally, Chapter 10 reviews the changes to the biota and puts the efforts made to conserve the indigenous biota into a global perspective.

The pace of change has not slowed and further species are even now declining towards extinction. Habitats continue to be lost or modified by activities such as forestry, mining, agriculture and urban sprawl. As the human population grows and the pressure on existing conservation lands intensifies, New Zealands clean, green image attracts a growing number of tourists who put ever-increasing demands on the natural environment they have come to enjoy. The risk of introducing rats and cats to islands where they do not yet occur, or introducing new species of animals, plants and micro-organisms to this country, intensifies as people and freight move freely between New Zealand and other parts of the world.

As we shall see, two facts of history are crucial to the story this book tells. First, New Zealand was isolated from the rest of the world for 80 million years; and second, it was the last land mass of any significant size to be discovered by humans. Today, New Zealand is part of the global village and contributes to, and is influenced by, problems such as over-population , economic growth, pollution and biodiversity loss.

In the face of all these pressures, New Zealanders have a responsibility to conserve as much as possible of this countrys distinctive biota and unique ecological communities. Each generation views change in relation to what things were like in their childhood, so the baseline for measuring change is steadily eroded. It must be measured not by what we, our parents or even our grandparents knew, nor by 1840 when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed and Maori and Pakeha supposedly became united under the British Crown. The real baseline against which we should measure change is the fauna and ecological communities that were present at the time the first humans discovered this country and left their rats behind. I believe that effective conservation requires knowledge of the factors that shaped the ecological communities of that time and the changes that have occurred since.

We may regret the loss of moa and giant eagles and the other species now extinct, and the likely impending loss of endangered species such as kakapo, kiwi and black stilt. However, if we appreciate what makes our animals different and what makes them vulnerable, we will be better able to conserve those taonga that remain.

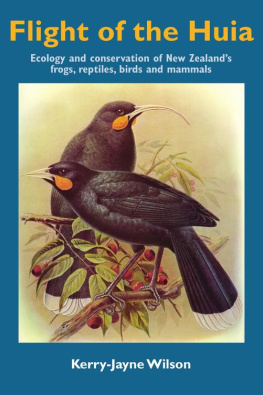

The title of this book was chosen for several reasons. The huia belongs to the endemic family Callaeatidae, whose affinities and origins have been lost in the mists of time. Like many New Zealand birds, the huia had reduced wings, so its flight was short, as was its time to extinction. It was revered by Maori, and huia tail feathers were worn by chiefs as a sign of rank. The bird was also of special interest to Pakeha. Male and female huia had very different bills and, according to early naturalists, different methods of feeding. Huia pairs were eagerly sought after by museums, and large numbers were collected, thus hastening, if not directly causing, their demise. Huia intrigue modern-day biologists. If the sexes did indeed have different methods of feeding, this would be unique among the worlds birds. Their cream-coloured bills contrasted with their glossy black plumage, suggesting that these might also have been used to attract mates. Like so many of New Zealands unique animals, there are aspects of this birds biology we may never understand.

A book of this type cannot be written without help from many people. Over the years numerous individuals have influenced my ideas, and it is literally impossible to list them all. Some sent me reprints of their research , some presented ideas at conferences, others over drinks at cafs or pubs, but of particular importance were discussions with colleagues in the field. In preparing this book I have read the work of hundreds of naturalists, ecologists, biologists and other natural scientists. I sincerely hope that those workers whose research I have cited will consider justice was done to their labours. It was impossible to tell all the fascinating stories I wanted to include in this book, and it was with regret that so much of the good work I read about could not be covered. I sincerely acknowledge the work and contributions of all those people.

I am grateful to my friends and colleagues in the Ecology and Entomology Group at Lincoln University. All members of the academic and support staff have assisted me in some way or another. They have all been willing to discuss ideas, read sections of manuscript, lend me books or journals, ferret out references or help in numerous other ways, but Adrian Paterson and Graham Hickling deserve special mention, for I sought advice from them so often. Thanks also to Eric Scott and Bruce Chapman, who were heads of department during the time this book was written. They gave me time to work on this project and provided departmental support. Erics set of the New Zealand Journal of Zoology saved me many a trip to the library. Most chapter drafts have been available to Lincoln University ecology students, and I appreciate the useful feedback I received from them. Certain students, some anonymously, drew my attention to references I had overlooked.

In order to write such a book as this, one needs access to a vast library or the support of exceptionally helpful library staff. Lincoln University has the latter. I thank various members of the universitys library staff for processing hundreds of interloans, for locating some obscure and ancient references, for their interest and encouragement throughout this project and for forgiving the occasional misdemeanour when borrowed material was returned late.

Chapter drafts were reviewed by Warren Chinn, Dr Richard Duncan, Dr Janet Greive, Dr Graham Hickling, Euan Kennedy, Dr Kim King, Dr Mike Imber, Dr Elaine Murphy, Dr Colin ODonnell, Dr Shaun Ogilvie, Dr Adrian Paterson, Dr Ralph Powlesland, Dr Murray Williams, Tony Whitaker and Trevor Worthy. I appreciate the time these busy people devoted to reviews of the manuscript and thank them for their helpful comments. Euan Kennedy, Adrian Paterson and Trevor Worthy each reviewed two or more complete chapters. I think Euan deserves my thanks for goading me into writing certain sections of Chapter 10.