B OWEN U NRAVELLED : A J OURNEY INTO THE F ASCIAL U NDERSTANDING OF THE B OWEN T ECHNIQUE

Julian Baker 978 1 905367 40 5 (UK) 978 1 583947 65 4 (US) 16.99/#29.95 168 pages 275 212mm paperback

The Bowen Technique, named after its originator Tom Bowen, has grown hugely in popularity since it was first taught in the 1980s. This book breaks down the concepts of The Bowen Technique and develops an understanding of what is going on during a treatment, including explanations of why things happen the way that they do.

Julian Baker is the principal of the European College of Bowen Studies, and is one of the worlds leading experts on The Bowen Technique, fascia and connective tissue.

F ASCIAL R ELEASE FOR S TRUCTURAL B ALANCE

James Earls and Thomas Myers 978 1 905367 18 4 (UK) 978 1 556439 37 7 (US) 24.99/#34.95 288 pages 275 212mm paperback

Fascial Release for Structural Balance combines manual therapy skills with the exciting new field of structural therapy, which employs the unique and newly discovered properties of fascial tissues. Through informed assessment and manipulation of fascial patterns, you can help eradicate many of your clients chronic strain patternsfor good.

The book is designed for any bodywork practitioner using manual therapy who can help their current and future clients by giving them a structural analysis and creating a treatment strategy using the techniques included in this book. The authors bring together a unique introduction to fascially informed structural anatomy with a method for postural analysis and detailed and easily applied techniques.

Thomas Myers has practiced integrative structural therapy for over 30 years in a variety of clinical and cultural settings. He is the author of Anatomy Trains (Elsevier 2001, 2009) and numerous collected articles for journals and trade publications.

The Walking System

Four legs good, two legs bad.

George Orwell , Animal Farm

The body divides itself into two units: passenger and locomotor. The passenger unit is responsible only for its on postural integrity .

Jacquelin Perry , Gait Analysis

Walking while nursing an injured arm in a cast throws off your balance and distorts your geometry of the walking body, creating various tensions and asymmetries that in themselves create further pain. My broken arm ached and it made the rest of my body ache, too .

Geoffrey Nicholson , The Lost Art of Walking

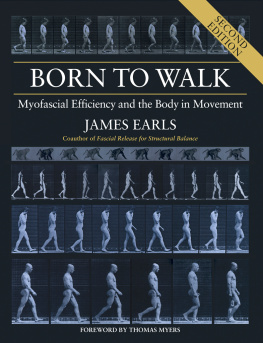

Walking on two legs requires a tremendous act of balance and is often described as controlled fallingif we do not successfully put one foot in front of the other, well fall to the ground. For our four-legged friends, walking must be so much easier, as they always have at least two points of contact with the ground at any one time. For us, walking requires the ability to have just one foot on the ground and to maintain some form of equilibrium within our tall, straight, and very unstable structures.

We walk to move around, to take our head and hands to other places, to achieve needs and desires. This apparently simple action requires a brain and nervous system; it demands internal planning and an ability to predict actions and reactions. It makes use of the many other cooperative senses that we have developed over millions of years. For elegant and efficient walking, each of our systemsespecially those of sight, balance, and sensationmust be communicating in harmony. This requires the coordination abilities of the brain and nervous system.

One of the inherent problems in the study of anatomy is that we organize anatomy by these systems. In breaking the organization of the body down into similar tissue types, we tend to focus our attention on just one system at a time. Ideally, we should talk about the walking system throughout this book, but, alas, that would be a much larger tome, and it would require knowledge beyond my capabilities. Therefore, I must limit myself to analyzing the bodys neuro-myo-fascial-skeletal-vestibular system, and my main focus will be on the myofascial elements and their cooperation.

Homo sapiens developed as generalists; we can adapt to many different situations, weaknesses, and disabilities. A glance at the people on any city street will quickly demonstrate various strategies for what we call walking. There are many factorsneurological, visceral, emotional, cultural, and structuralthat can alter how we walk. The number of possible interactions within those factors would be too large to list and would possibly require consultation with just as many professionals to unravel. It is for that reason that I will concentrate on developing a model of normal, nonpathological gait.

This book presents a version of what can happen when the whole body is allowed to move together. I hesitate to call it normal, but it is a pattern that is inherent within most of uswithin the lines and grooves, contours and forms of our inherited anatomy. It is the relaxed, repetitive walking that allows our brains to be otherwise occupied, facilitating our gift to walk and talk, to philosophize, to compose, to fall in love, to meander through any number of human preoccupations. It is a gift eulogized by manyfrom the peripatetic philosophers to Wordsworth and Dickensand a facility brought about through what Bernstein (the founder of motor-control theory) referred to as level B functioning. Walking, according to Bernstein, uses synergy among many different muscles, coordinated without any input from the brain, relying on self-monitoring by the proprioceptive system (Latash 2012). In our exploration of the myofascial system, we will see how the mechanoreceptors are located within the fascial tissue and seem to form a computation system that allows walking to be a subconscious activity.

Your body is built for walking .

Gary Yanker

I believe the whole body walks. That might sound like a ridiculously obvious thing to say, but many schools of thought exist in the modeling of gait that narrow their gaze to analyzing just one aspect of human motion. One of the most widely accepted theories splits the body into locomotor and passenger sectionsthe pelvis and lower limbs versus the head, arms, and trunk (Perry and Burnfield 2010). Another school of thought, put forward by Gracovetsky, suggests that we only require the deep spinal muscles to move (2008). The alternate contraction of the multifidi, he argues, gives us the rotational movement we need to propel ourselves in any direction.

While there is certainly a truth in each of these theories, they arefor mequite incomplete. We use the whole body to walk: the pelvis and legs are assisted by the trunk and the arms. The whole body helps balance and movement by increasing and decreasing the forces moving through the soft tissue. The whole body also works to lessen the amount of distortion that reaches the head. We need to keep our eyes relatively level, and we certainly do not want the force of impact rattling our brains at each heel strike, so we require the trunk and shoulder girdles to constantly adapt to keep the head steady.

The three elements of the walking system I will focus on most will be the fascial, muscular, and skeletal elements. These combine to form a wonderful, symbiotic map of the forces that travel through the body. The shapes and contours of the bones and their joints create pathways, like dry riverbeds, which, come the flood, will direct the water along preferred paths. The bones and joints assist the body through a controlled pattern of shock absorption, with the folding of joints taking place along predictable lines that send the force of impact into the semifluid streams of myofascial tissue.