FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, JULY 2004

Copyright2003 by Thomas Cahill

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Nan A. Talese, an imprint of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2003.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

THE HINGES OF HISTORY is a registered trademark belonging to Thomas Cahill.

constitute an extension of this copyright page.

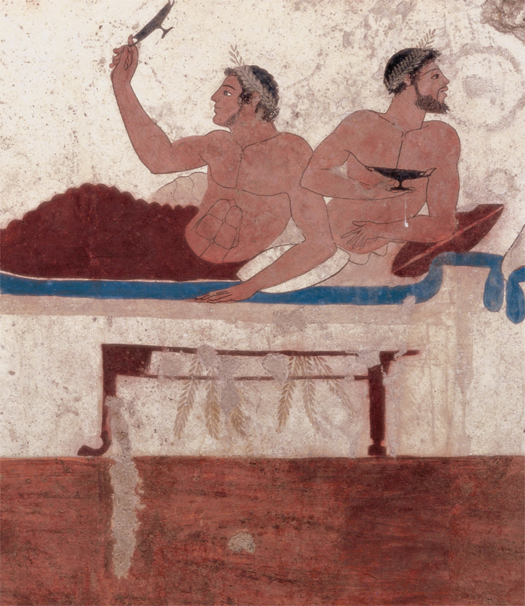

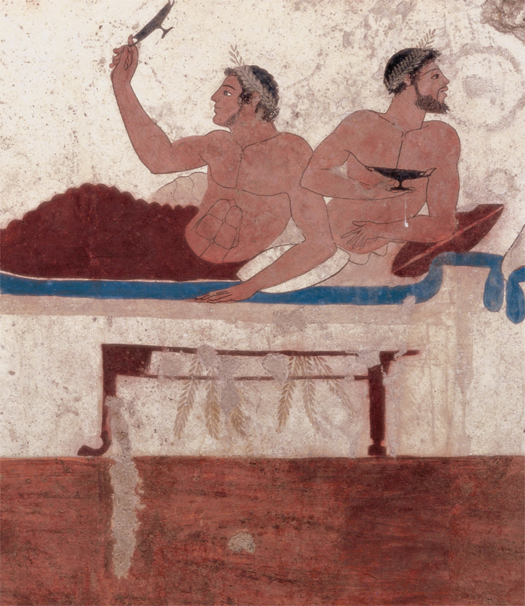

Endpaper: Symposium, Tomba del Tuffatore, lastra nord, 480 B.C., Paestum, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, foto pedicini

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Nan A. Talese/Doubleday edition as follows:

Cahill, Thomas.

Sailing the wine-dark sea : why the Greeks matter / Thomas Cahill.1st ed.

p. cm.(Hinges of history ; v. 4)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. GreeceCivilizationTo 146 B.C. 2. Civilization, WesternGreek influences. I. Title. DF77.C28 2003

909.09821dc21

2003050725

eISBN: 978-0-307-75512-4

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

Map art by Jackie Aher

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

Symposium, Tomba del Tuffatore, lastra nord, 480 B.C.

Symposium, Tomba del Tuffatore, lastra nord, 480 B.C.

To

MADELEINE LENGLE

and

LEAH & DESMOND TUTU

and in memory of

PAULINE KAEL

mentors and models of life and art

The heart within me never changes toward you so beautiful

One can achieve his fill of all good things,

even of sleep, even of making love

HOMER

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Way They Came

I: THE WARRIOR

How to Fight

II: THE WANDERER

How to Feel

III: THE POET

How to Party

IV: THE POLITICIAN AND THE PLAYWRIGHT

How to Rule

V: THE PHILOSOPHER

How to Think

VI: THE ARTIST

How to See

VII: THE WAY THEY WENT

Greco-Roman Meets Judeo-Christian

INTRODUCTION

THE WAY THEY CAME

Demeters hair was yellow as the ripe corn of which she was mistress, for she was the Harvest Spirit, goddess of farmed fields and growing grain. The threshing floor was her sacred space. Women, the worlds first farmers (while men still ran off to the bloody howling of hunt and battle), were her natural worshipers, praying: May it be our part to separate wheat from chaff in a rush of wind, digging the great winnowing fan through Demeters heaped-up mounds of corn while she stands among us, smiling, her brown arms heavy with sheaves, her ample breasts adorned in flowers of the field.

Demeter had but one daughter, and she needed no other, for Zeuss help, the mother retrieved her daughter, but Persephone had already eaten a pomegranate seed, food of the dead, at Hadess insistence, which meant she must come back to him. In the end, a sort of truce was arranged. Persephone could return to her sorrowing mother but must spend a third of each year with her dark Lord. Thus, by the four-month death each year of the goddess of springtime in her descent to the underworld, did winter enter the world. And when she returns from the dark realms she always strikes earthly beings with awe and smells somewhat of the grave.

H ISTORY MUST BE learned in pieces. This is partly because we have only pieces of the pastshards, ostraca, palimpsests, crumbling codices with missing pages, newsreel clips, snatches of song, faces of idols whose bodies have long since turned to dustwhich give us glimpses of what has been but never the whole reality. How could they? We cannot encompass the whole reality even of the times in which we live. Human beings never know more than part, as through a glass darkly; and all knowledge comes to us in pieces. That said, it is often easier to encompass the past than the present, for it is past; and its pieces may be set beside one another, examined, contrasted and compared, till one attains an overview.

Like fish who do not know they swim in water, we are seldom aware of the atmosphere of the times through which we move, how strange and singular they are. But when we approach another age, its Every old shoe finds an old sock. I had been to a farm once but had never seen harrow or plough in use, I knew what coal was but had never been warmed at an open coal fire, I surely knew what shoes and socks were but nothing of the archaic courting practices in the Irish countryside. My mother explained patiently that this last was meant as a hilarious sendup of old maids and their prospects. The sexual aspect of the imagery she doubtlessly left me to work out for myself. But her waves of words had a sort of triple (and simultaneous) effect: first, the experience of coming into contact with alien lives through the medium of the words they had left behind; then, an acknowledgment of the humanity I shared with these strangers from another time and place; and, last, the satisfying thrill that concentrated, metaphorical language can give its listenerthe electric sensation at the back of the neck announcing the arrival of the gods of poetry.

It is through such wisps of words and such tantalizingly incomplete images that we touch the past and its peoples. When I attended a Jesuit high school in New York City and was taught to read artsickness, fevered attempts to protect her children, and catatonic despair. I too had known impossible opponents; I too understood how much a mother loved her children.

Just around the corner from my school was the Homers metaphors: the wine-dark sea, the rosy-fingered dawn. I had, without knowing it, put the literature in a context.

I tell you these things now because my methods of approaching the past have scarcely changed since childhood and adolescence. I assemble what pieces there are, contrast and compare, and try to remain in their presence till I can begin to see and hear and love what living men and women once saw and heard and loved, till from these scraps and fragments living men and women begin to emerge and move and live againand then I try to communicate these sensations to my reader. So you will find in this book no breakthrough discoveries, no cutting-edge scholarship, just, if I have succeeded, the feelings and perceptions of another age and, insofar as possible, real and rounded men and women. For me, the historians principal task should be to raise the dead to life.