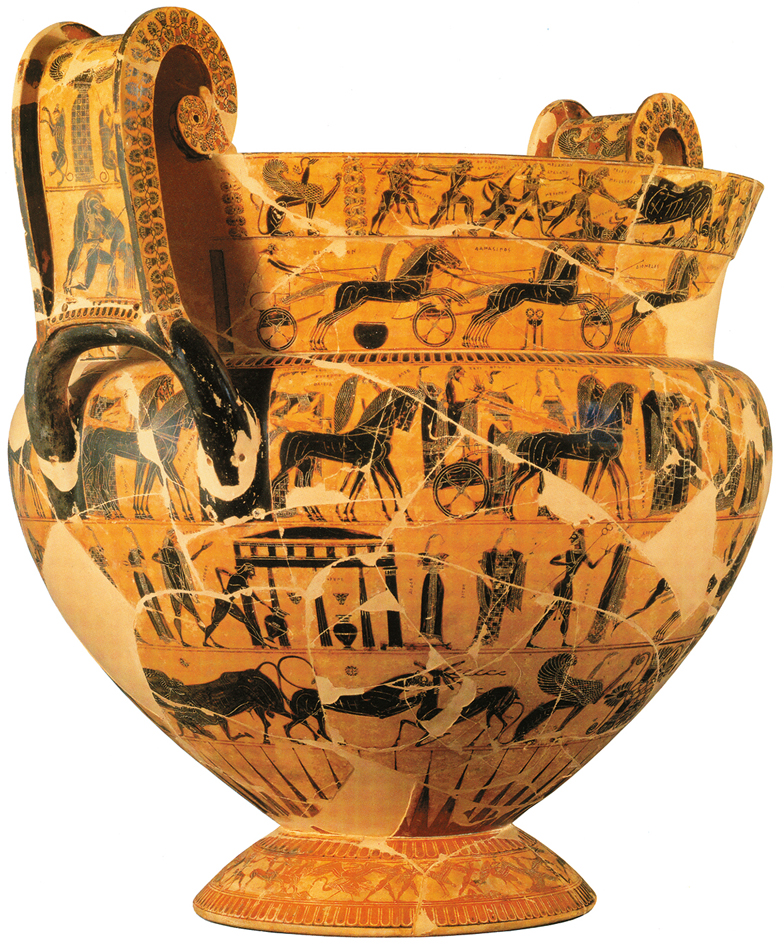

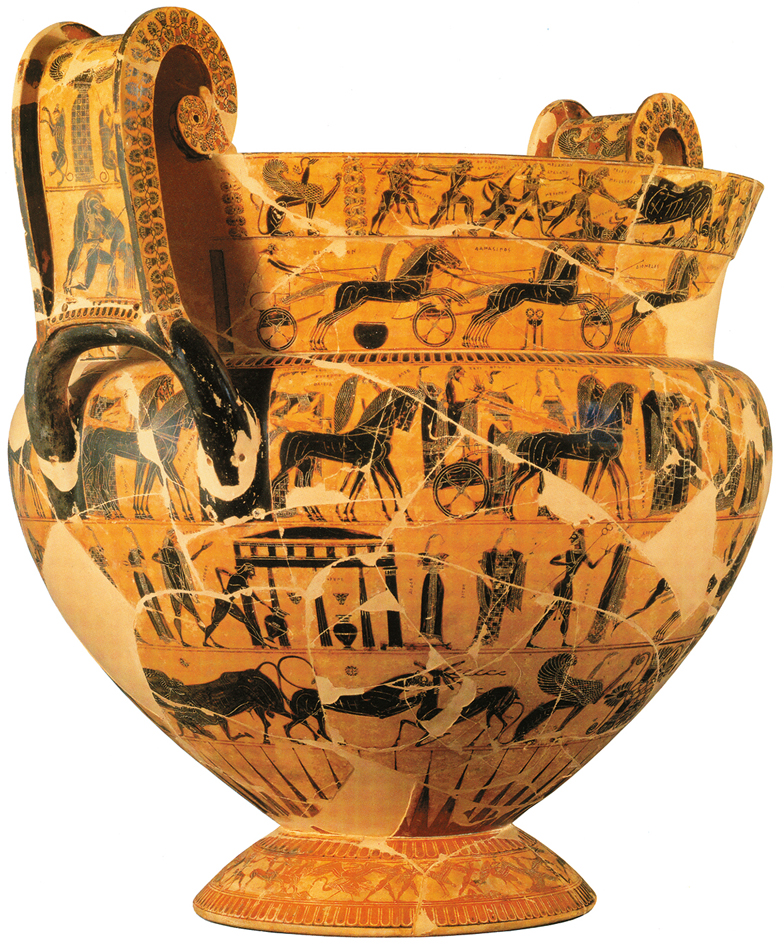

The Franois Vase. Attic black-figure volute-krater from Chiusi, signed by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias, side A, c. 570. 66 cm (26 in.)

About the Author:

T. H. Carpenter is the Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Ohio University, where he has taught since 1997. He was awarded a masters degree in theology from Harvard University and, after earning his doctorate in classical archaeology at Oxford University, he worked for four years as chief researcher at the Beazley Archive at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Professor Carpenters other books include Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-century Athens (1997) and Mythology: Greek and Roman (1977).

Contents

In recent decades many theories have been proposed for the interpretation of Greek myths; however, the reader will quickly notice that none of them is mentioned here. This is in part because even a summary review of the theories is far beyond the scope of this small book, and in part because the focus here is on identification rather than on interpretation.

The primary purpose of this book is to help readers identify scenes from myth in Archaic and Classical Greek art while at the same time showing that the depictions often need to be seen in a developmental context to be understood. My intention has been to provide a dependable groundwork on which further studies can be built since it is my firm conviction that interpretation can only follow careful examination, identification, determination of a chronological context, and recognition of patterns of development (when they exist).

Questions of what specific meaning certain myths may have had for a particular polis, or for Greeks in general, will certainly occur to readers, as will questions as to why a particular scene was put on a vase or shield band or temple pediment, or why it was depicted one way and not another. These are important questions, and it is my hope that observations here may give some basis for seeking answers to them.

Limestone metope from Selinus. Perseus beheads Medusa who already holds the winged horse Pegasos. Athena, without attributes, stands beside him. c. 530. 1.47 m (57 in.)

Most surveys of Greek mythology are, quite rightly, based on literary sources, since these are the principal repositories of ancient myths. Some surveys include the occasional ancient sculpture or painted vase as illustrations, some use a mixture of ancient, renaissance and modern art, and still others use new works specifically created for them, but in few cases is the reason behind the choice of illustrations or the connection between them and the text at all clear. The scenes float in a kind of ahistorical limbo.

In fact, ancient Greek art is also a rich source for the knowledge of myths and one that can be studied in its own right. The way a story is shown may develop and change over a period of time, so that a depiction of a myth from 580 BC will probably be very different in content (as well as in form) from a depiction of the same myth in 400 BC. Sometimes a story is shown for which no literary source survives, sometimes the details of the story shown are quite different from those in literary versions, and sometimes life is given to a story known only in a late and abbreviated form.

This book is an introductory survey of myth as it appears in surviving ancient Greek visual arts created between about 700 and 300 BC. Though some familiarity with the Homeric epics and Greek tragedies is assumed, the book is intended for the interested general reader as well as for the student of classics or of myth. It begins with a brief survey of the types of ancient sources that have come down to us and continues with an examination in some depth of the development in art of two myths as a demonstration of a method for such studies. The largest part of the book, however, is a survey of the development of some of the more important myths (a word used here to encompass heroic legends as well as stories of the gods).

The focus is ancient Greek narrative art depictions of scenes that tell stories. Thus, portraits of the gods are only of interest as they define attributes by which a deity may be recognized in narrative scenes, and, as a result, few non-architectural free-standing sculptures and few coins are included here, since often they simply repeat (and perhaps refine) a type established much earlier on. By Greek art not only the art of the Greek Aegean East Greece, the islands, the mainland and the Peloponnese is meant, but also the work of Greek artists or their followers in the West particularly South Italy (Magna Graecia) and Sicily.

A starting point of 700 BC is chosen because this is roughly the date when the first certain depictions of myth appear in Greek art, on Attic vases. An end point of 300 BC is chosen in part because the death of Alexander traditionally marks the end of the Classical period, and in part because it is towards the end of the 4th century that Attic vases painted with narrative scenes, one of our most important sources, finally ceased to be produced.

The traditional terms Geometric, Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic are used here as names for historical periods and stages in the development in Greek art. Geometric refers to the period from about 900 to 700 BC when Greek art began to be revitalized after the stagnation of the dark ages that followed the destruction of the Mycenaean world. The art of this period, mostly painted vases and small bronzes, is characterized by the use of geometric forms of decoration (as opposed to free forms). Stylized human figures in narrative scenes appear on vases by about 750 BC, but scenes from myth do not occur before the end of the century. Trade with the East developed during the late 8th century and the influence of Eastern forms and styles is clear in Greek art of the 7th century the term orientalizing is often used to describe the new developments through which geometric forms give way to more natural ones and fantastic figures and shapes proliferate. The 6th century was a time of consolidation and prosperity in Greece, and the term Archaic is used to describe the art of this period. This was, without any question, the most creative period for the depiction of myths in art, and many of the conventions established then carried on into later times. The sack of the Acropolis in Athens by the Persians in 480 BC and the subsequent destruction of the Persian fleet by the Athenians traditionally marks the end of the Archaic period and the beginning of the Classical, when Greek art reached its full and powerful maturity. The term Hellenistic, then, is used to describe the history and art of the Greek world from the death of Alexander in 323 on into the 1st century BC. The great social and political changes during the Hellenistic period are paralleled by great changes in the way myths were understood and depicted, but these changes are beyond the scope of this book.

Next page