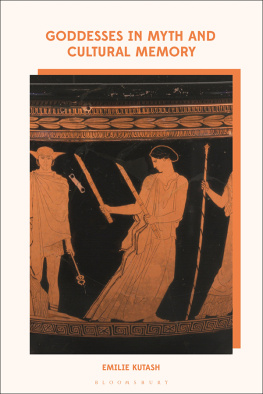

Female Mobility and Gendered Space

in Ancient Greek Myth

Also available from Bloomsbury

Dancing for Hathor, Carolyn Graves-Brown

Greek and Roman Sexualities: A Sourcebook, Jennifer Larson

Women in Ancient Greece, Bonnie MacLachlan

Women in Greek Myth, Mary R. Lefkowitz

Womens Life in Greece and Rome, Mary R. Lefkowitz

Female Mobility and Gendered Space

in Ancient Greek Myth

Ariadne Konstantinou

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This book grew out of my doctoral dissertation, submitted to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2013, and written with the generous support of the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation and Hebrew Universitys Humanities PhD Honours Program (Presidents Fellowship). I am grateful to Deborah Gera for her continuous teaching, close supervision and great patience during that time. Since then, the books content has been substantially reorganized, revised and expanded. I have been fortunate to obtain post-doctoral fellowships at the University of Toronto, Tel Aviv University and Bar Ilan University, which allowed me to revise the material and prepare it for publication. Andrea Rotstein served as sponsor during a postdoctoral year at Tel Aviv University; her generosity and sincere interest in my work were indispensable.

I also benefited from the advice and support of several colleagues and friends. Early on, Rachel Zelnick-Abramovitz shared over coffee with me much useful advice on how to revise the material towards publication and made many helpful suggestions at the crucial stage of preparing the book proposal. She was also the one to recommend Bloomsbury Academic and I am extremely thankful to her for helping me find the most appropriate home for my book. I am deeply grateful to Margalit Finkelberg for her invaluable comments on several chapters of the book, for her interest in my work and progress, and for her generous guidance and encouragement on all things academic, way beyond the book. Chloe Balla provided constant support and advice, always a phone call or email away, and always ready to read and criticise my work with much love and skill. I am also thankful to Daniela Dueck, Alexandra Trachsel and Jonathan Cahana, who each read and commented on a chapter of the book, and to Talia Trainin and Su Schachter who helped with my English. I would also like to thank Alice Wright and her colleagues at Bloomsbury Academic for their professionalism and care during the long process of turning a manuscript into a book. Clara Herbergs guidance and assistance at the final stages was instrumental. Of course, I am the only one responsible for the outcome.

also appear in my article To the Mountain: The Ritual Space of Maenadism in the Athenian Imaginary, in W. Friese, S. Handberg and T. M. Kristensen (eds), Ascending and Descending the Acropolis: Sacred Travel in Ancient Attica and its Borderland, Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

My father Vasilis read the whole manuscript in the role of a general (but, alas, non-objective) reader, and my siblings Anna and Alexander and their families always had a word of encouragement at hard times. My father and his partner Dorilea Ioakimidou have been loving and supportive in every possible way, and for two summers in Thessaloniki created the perfect conditions which allowed me to focus on my work. My mother Ilana passed away shortly after I narrowed down the topic of the dissertation more than ten years ago, so we only had the briefest chance to talk about it. I miss her advice and unique perspective on things every day. I would never have been able to complete this book and the dissertation it grew out of without the love and support of my spouse Shlomi Peled, who constantly balances me by showing me the half-full glass in life and always encourages me to aim higher. Raising our children Daphne and David is hard work and endless joy for us. There are no words to express my love and gratitude and so this book is dedicated to him.

Unless otherwise noted, the quoted Greek texts are from the most recent edition of the Oxford Classical Texts series and the translations are mine. Translations aim at clarity rather than elegance. References to Classical texts follow the abbreviations of S. Hornblower, A. Spawforth and E. Eidinow, eds (2012), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Transliteration of Greek names is a problem many classicists encounter, often suggesting idiosyncratic solutions. I opted to write the more common names in their more familiar Latinized forms, and have kept stricter transliteration rules for what I thought were more uncommon names.

A few years ago, I happened to see from the balcony of our apartment at the heart of cosmopolitan Tel Aviv people dancing in the streets during the Jewish festivity of Simchat Torah. The holiday celebrates the end of the one-year cycle of Torah reading and marks the beginning of the new cycle. The tradition of Hakafot, during which the Torah scrolls are taken out of the ark and carried around the synagogue seven times, often also spills over to dancing in the nearby streets. This, of course, was not the first time I had witnessed religious celebrations in the streets: growing up in Greece, I had plenty of opportunities to watch or participate in religious processions. What was strikingly different on this specific occasion was my perspective.

The balcony of our second-floor apartment opens up into a small street, both close enough for every detail to be visible, yet distant enough to yield a general impression. This heightened viewpoint is somewhat different from that of an onlooker standing at street level while the celebrants pass by. Rather than the festive atmosphere of this happy celebration, what caught my attention was the realization that the very familiar, yet public area of the small street just outside my apartment building temporarily metamorphosed into a ritual space. Not only was all traffic suspended to give way to the procession, but the ritual space was also divided by gender, seeming to follow the segregation still prevalent in the majority of Orthodox synagogues. The men, all dressed in festive white shirts, led the procession, singing and dancing around the Torah scrolls, while the women and children trailed at the back, chatting and taking care of the younger children with strollers.

Whoever has partaken in or witnessed this or similar processions might find nothing striking in this description; on the contrary, it even verges on the banal. And yet, it evoked in me at the time the realization that my particular perspective on this procession might serve as an apt equivalent to imagining gendered spaces in ancient Greek contexts, be it within ritual contexts or beyond them. The Simchat Torah procession outside my home revealed to me how a public and familiar location may momentarily become a ritual space. My own standing at the window looking out resembled, for a moment, my scholarly work on the ancient Greek material of my study close enough and far removed at the same time.

The gender segregation observed in the festivity of the congregation is virtually non-existent in the secular modern life of Tel Aviv, yet it felt as though there were a huge glass wall separating male and female celebrants and, though invisible to me, everyone partaking in the procession was familiar enough with the tradition and seemed content to preserve it. The incongruous (to my eyes) gender segregation in a public space and the huge glass wall disappeared the moment the celebrants faded away at the end of the street. They probably returned to their synagogue and continued their celebrations, while our small and familiar side street reverted to its dull existence of hosting cars and pedestrians in the busy city centre. I return to this idea of glass walls in , a metaphor coined by feminists to describe the invisible barriers that prevent the advancement of women and other minorities at work. It is used in this context as a constructive metaphor through which to think about the limits of female mobility in ancient Greek mythic thought.

Next page