Anita Reichle

Theres a reason so much of the best utopian literature is fiction. Utopia is by definition unreal, unattainable. Non-fiction accounts of utopian communities descend quickly into sordid exposs, or memoirs of troubled childhoods. They have difficulty reconciling the soaring ambition, the noble impulses, with messy reality. Ambition and impulse are the stuff of dreams; this is territory better traversed by the capaciousness of fiction.

Auroville is not a utopia. It is a complex, lived and very real community of some 2500 people nestled above the Indian Ocean, on the Bay of Bengal. Dotted with schools and restaurants and shops and sports centres, it is enveloped in the uncertainties and ambiguities of humankind. The community is, as we Aurovilians like to say, a living laboratory: a not-quite-yet defined experiment, an incipient society searching for new models of economy, politics, aesthetics, culture.

Yet there are no doubt utopian aspects to the community. It is founded on and structuredhowever looselyaround certain ideals. Its residents and institutions are unabashedly aspirational, their existence predicated on the premise that alternatives are attainable, that a better world is realizable. Although lacking a formal constitution, the community is guided through the precepts set out by its founder, the Frenchwoman Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa, known as the Mother, in the Auroville Charter (see page xxiii).

This year, 2018, Auroville celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. It is a remarkable achievement: few intentional communitiesanywhere in the world, at any point in historyhave survived as long. Of course those fifty years have revealed some of the difficulties in manifesting a better world. Auroville has made some genuine achievements, but it has also faced formidable setbacks. Hence the title of this anthology: Dream and Reality. Utopia signals perfection, but perhaps the most truly utopian aspect of Auroville is the oscillation in daily life between the search for perfection and the strictures of a chronically imperfect human nature.

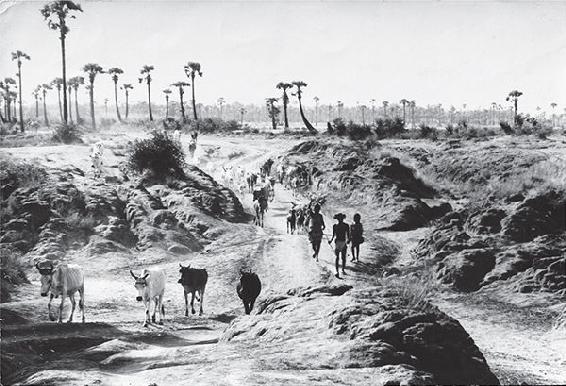

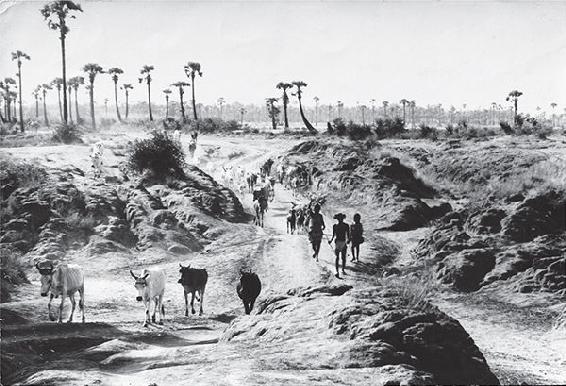

Greetings from Auroville to all men of goodwill. Are invited to Auroville all those who thirst for progress and aspire to a higher and truer life. These were the words, the Mothers, broadcast live on radio, that rang out across a barren south Indian plateau one blazing morning, on 28 February 1968. A crowd of more than 5000 people had gathered in a makeshift amphitheatre to mark Aurovilles formal inauguration. They came by bus, by car, they streamed in by foot across the open land. Dignitaries, hippies, aspiring yogis, local farmers and fishermen: all eager to see and perhaps take part in this new experiment in collective living.

The events of that day are described in this anthology by the author Navoditte (Norman Thomas). He remembers silence, a seriousness of purpose, and then a gong followed by the Mothers broadcast. A group of youth mixed earth from 124 countries and twenty-three Indian states in a marble urn, a symbolic enactment of human unity. Participants at the inauguration sensed a shiver down their spines; one compared the occasion to a meteor landing in the desert. It felt like an epic moment. Something momentous was beginning.

The inauguration of Auroville was, however, just thatthe beginning of a journey, a fledgling if daring step into the unknown. Fifty years on, much about Auroville (including its final destination) remains unclear. But when I set out to assemble this anthology of writing from Auroville, I did so with the knowledgeas someone who has spent nearly his entire life in the communitythat the journey itself is much less mysterious, and has over the years acquired a distinctive character and identity. There is much one does not, perhaps cannot, know about Auroville. There is a lot, too, that one can say about itand, indeed, as attested to by the pieces in this collection, that has been said.

I began by sorting through volumes in the Auroville library. I soon found myself in a dusty basement, in the Auroville Archives, poring over ancient periodicals, unpublished memoirs, meeting reports, diaries, journals. It became apparent that there were certain recurring themes in the Auroville experience. Those themes, cutting across the decades, encountered by generation after generation, provide the structure for this anthology. The section on The Earth, for instance, portrays an ongoing effort to settle the land, to manifest and give concrete shapein the form of buildings, forests, parks, roadsto the lofty ideas that inspire Auroville. For Aurovilles pioneers, the concern was primarily with overcoming an inhospitable desert; they responded by planting trees, millions of them, and the result has been arguably the most successful afforestation programme in India (the contours of that programme are described, with characteristic wit, by the late biologist Rauf Ali). Later generations have faced different challenges, notably divisions within the community itself over the best pattern of development. Those divisions are also captured in The Earth, particularly in the sharply divergent visions expressed by two authors, Rishi Walker and Anu Majumdar.

Dominique Darr

Aurovilians are tasked with nothing less than reinventing society. This is no small endeavour. Work conveys one of the communitys grandest ambitions, and also greatest challenges. In a 1954 document entitled The Dream (see page xxiii), the Mother writes that money would no longer be the sovereign lord in a place like Auroville. What does this mean in practice? And how does Auroville build an economy without money (and without all the accompanying capitalist paraphernalia) in a world where money is indeedand perhaps increasinglyvery much the lord? The community has yet to find practicable answers to these questions. Perhaps, though, it deserves credit for tryingfor experimenting with different models of society and economy, for at least making the effort to surmount convention and orthodoxy.