Character DISTURBANCE

The Phenomenon of Our Age

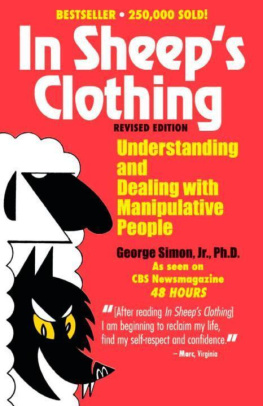

Dr. George Simon

Parkhurst Brothers, Inc., Publishers

LITTLE ROCK

Copyright 2011 by George K. Simon, Ph.D. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except for brief passages quoted within reviews, without the express prior written consent of Permissions Director, Parkhurst Brothers, Inc., Publishers.

www.pbros.net

Parkhurst Brothers books are distributed to the trade through the Chicago Distribution Center, a unit of the University of Chicago Press, and may be ordered through Ingram Book Company, Baker & Taylor, Follett Library Resources and other book industry wholesalers. To order from the University of Chicagos Chicago Distribution Center, phone 1-800-621-2736 or send a fax to 1-800-621-8476. Copies of this and other Parkhurst Brothers, Inc., Publishers titles are available to organizations and corporations for purchase in quantity by contacting Special Sales Department at our home office location, listed on our website.

Printed in Canada

First Edition 2011

12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: Consult publishers website.

ISBN: Hardcover: 978-1-935166-32-0 [10 digit: 1-935166-32-8]

ISBN: Trade Paperback: 978-1-935166-33-7 [10-digit: 1-935166-33-6]

ISBN: 978-1-935166-34-4 (electronic)

This book is printed on archival-quality paper that meets requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences, Permanence of Paper, Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Design Director and Dustjacket/cover design:

Wendell E. Hall

Page design:

Shelly Culbertson

Acquired for Parkhurst Brothers, Inc., Publishers by:

Ted Parkhurst

Editor:

Roger Armbrust

Proofreaders:

Bill and Barbara Paddack

DISCOUNTS FOR BULK PURCHASE: Institutions, schools, and organizations may purchase this title in bulk at substantial savings off the suggested list price. Please email randy@pbros.net or refer to our website www.pbros.net for current contact information from our Special Sales Department.

For Sherry,

whose heart is truer than any I know,

and who inspires me daily to be

a better person. And for all those silent

but committed souls of noble character,

upon whom the very survival

of freedom depends.

Acknowledgements

Im deeply grateful to my wife, Dr. Sherry Simon, and my entire family not only for their unwavering support, patience and understanding, but also for the invaluable lessons they have taught me about conducting a life of meaning and character.

I owe a supreme debt to the hundreds of weblog readers, workshop attendees, online reviewers, and other supporters who have taken the time to write and share their experiences. Their insights and comments have helped me to clarify perspectives and to modify my work to better address their needs.

This book draws from the works of many theorists and researchers. I am particularly indebted to Theodore Millon, Stanton Samenow, and Robert Hare for their remarkable contributions to the understanding of personality and character.

Finally, Id like to thank Ted Parkhurst of Parkhurst Brothers, Publishers for his understanding, support, and encouragement, as well as Roger Armbrust for his expert editing and kind suggestions for clarifying my message.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Neurosis and Character Disturbance

Chapter 2

Major Disturbances of Personality and Character

Chapter 3

The Aggressive Pattern

Chapter 4

The Process of Character Development

Chapter 5

Thinking Patterns and Attitudes Predisposing Character Disturbance

Chapter 6

Habitual Behavior Patterns Fostering and Perpetuating Character Disturbance

Chapter 7

Engaging Effectively and Intervening Therapeutically with Disturbed Characters

Epilogue

Neurosis and Character Disturbance

Preface

Imagine you recently read a newspaper article about a young girl who suddenly and inexplicably lost her eyesight. Her frantic parents took her from doctor to doctor, specialist to specialist, and clinic to clinic, yet no one could find the reason for her blindness. In desperation, one day they decided to take her to a psychologist. After months of traditional psychoanalysis, the therapist revealed that the childs blindness resulted from severe emotional trauma. It seems that several months before, while riding on the school bus, this young lady just happened to glance at a boy seated with some friends across the aisle. She thought to herself: This guy is really cute. Before long, she also began thinking things like: I wonder what it would be like to kiss him. But almost immediately after having these thoughts, she started to feel badly. She began fretting about what kind of horrible person she must be to entertain such impure thoughts. She worried that they could only lead to other impure urges and temptations, and even perhaps some impure action on her part. Eventually, she became consumed with guilt and shame. She remembered times in the past when she had looked at boys, and how hard it was to resist impure thoughts and urges. Surely worse would follow, she feared, if she didnt keep herself in check. Shortly after this incident, she lost her vision.

When she first saw the psychologist, this troubled little girl didnt even remember the bus incident. She certainly didnt remember what she was thinking or feeling at the time. Shed even forgotten how deeply the incident unnerved her, and how she dealt with her anxiety over the situation. The psychologist helped her see that she had repressed her memories as a way of easing the intensity of her emotional pain. Her lengthy analysis eventually helped her not only recover her memory of that fateful days events, but also enabled her to re-connect with her conflicted emotions. She came to realize this: She was so deeply distressed by what she thought were her unforgivable, impure desires that she actually believed it was better not to see at all than risk having such thoughts about boys again.

Once she had confessed her sins to the doctor and he did not condemn her, the young girl slowly began to feel better. She took heart in the notion that he appeared to accept her just as she was. She slowly began to feel that she wasnt such a horrible person after all merely for the kinds of thoughts she sometimes had about boys. In time, she came to believe that the level of her fear, guilt, and shame was excessive and unwarranted, given the nature of the situation. No longer believing that simply having thoughts about kissing boys was as evil as she once did, she allowed herself to see again.

Now, I would pose to you, the reader, the same question I ask of professionals and non-professionals alike at every one of the hundreds of workshops Ive given over the past 25 years. How many scenarios similar to the one I described have you read or heard about in the last year? How about the past five years? How about the past, 10 20 30 years? It should come as no surprise that the answer I get is always the same: zero . What should shock you, however (and always gets the attention of my audiences), is this: Almost all of the principles of classical-psychology paradigms stemmed from various theorists attempts to explain this and similar phenomena (sometimes referred to by adherents to these theories as hysterical blindness).

You see, in Sigmund Freuds day, some individuals actually suffered from such strange maladies. Its important to note, however, that these extreme psychological illnesses were never widespread phenomena. But in the intensely socially repressive Victorian era, cases appeared of persons experiencing extraordinary levels of guilt or shame merely for being tempted to act on a primal human instinct, and displaying pathological symptoms as a result. If there were a motto or saying that might best describe the zeitgeist (i.e. social or cultural milieu) of that time it would be: Dont even think about it! So, some individuals were quite unnecessarily consumed with excessive guilt and shame about their most basic human urges. Freud treated some of these individuals, most of whom were women, typically subjected to more oppression than men. He eventually coined the term neurosis to describe the internal struggle he believed went on between a persons instinctual urges (i.e. id ) and their conscience (i.e. superego ), the excessive anxiety or nervous tension that often accompanies this internal war, and the unusual psychological symptoms a person can develop when attempting to mitigate (i.e. through the use of marginally effective defense mechanisms ) the intense emotional pain associated with these inner conflicts. He then developed a set of theories and constructs that appeared to adequately explain how his patients developed their bizarre maladies. In the process, however, he also came to believe that he had discovered universal, fundamental principles that explained personality formation and the entire spectrum of human psychological functioning .

Next page