James Ledbetter - One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries

Here you can read online James Ledbetter - One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Liveright, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

One Nation Under Gold examines the countervailing forces that have long since divided Americawhether gold should be a repository of hope, or a damaging delusion that has long since derailed the rational investor.

Worshipped by Tea Party politicians but loathed by sane economists, gold has historically influenced American monetary policy and has exerted an often outsized influence on the national psyche for centuries. Now, acclaimed business writer James Ledbetter explores the tumultuous history and larger-than-life personalitiesfrom George Washington to Richard Nixonbehind Americas volatile relationship to this hallowed metal and investigates what this enduring obsession reveals about the American identity.

Exhaustively researched and expertly woven, One Nation Under Gold begins with the nations founding in the 1770s, when the new republic erupted with bitter debates over the implementation of paper currency in lieu of metal coins. Concerned that the colonies thirteen separate currencies would only lead to confusion and chaos, some Founding Fathers believed that a national currency would not only unify the fledgling nation but provide a perfect solution for a country that was believed to be lacking in natural silver and gold resources.

Animating the Wild West economy of the nineteenth century with searing insights, Ledbetter brings to vivid life the actions of Whig president Andrew Jackson, one of golds most passionate advocates, whose vehement protest against a standardized national currency would precipitate the nations first feverish gold rush. Even after the establishment of a national paper currency, the virulent political divisions continued, reaching unprecedented heights at the Democratic National Convention in 1896, when presidential aspirant William Jennings Bryan delivered the legendary Cross of Gold speech that electrified an entire convention floor, stoking the fears of his agrarian supporters.

While Bryan never amassed a wide-enough constituency to propel his cause into the White House, Americas stubborn attachment to gold persisted, wreaking so much havoc that FDR, in order to help rescue the moribund Depression economy, ordered a ban on private ownership of gold in 1933. In fact, so entrenched was the belief that gold should uphold the almighty dollar, it was not until 1973 that Richard Nixon ordered that the dollar be delinked from any relation to goldcompletely overhauling international economic policy and cementing the dollars global significance. More intriguing is the fact that Americas exuberant fascination with gold has continued long after Nixons historic decree, as in the profusion of late-night television ads that appeal to goldbug speculators that proliferate even into the present.

One Nation Under Gold reveals as much about American economic history as it does about the sectional divisions that continue to cleave our nation, ultimately becoming a unique history about economic irrationality and its influence on the American psyche.

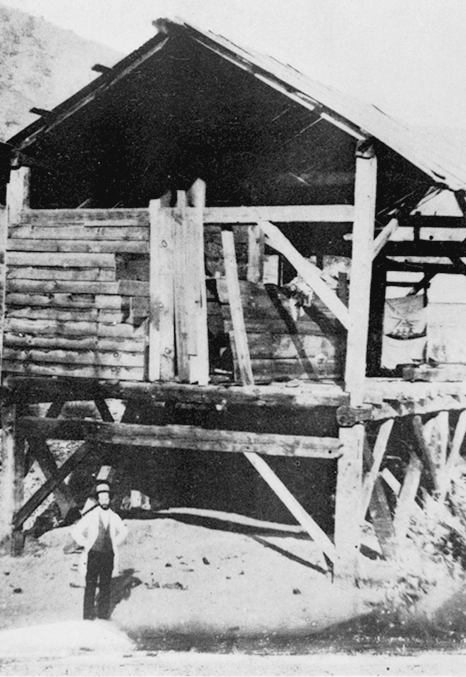

16 pages of illustrationsJames Ledbetter: author's other books

Who wrote One Nation Under Gold: How One Precious Metal Has Dominated the American Imagination for Four Centuries? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.