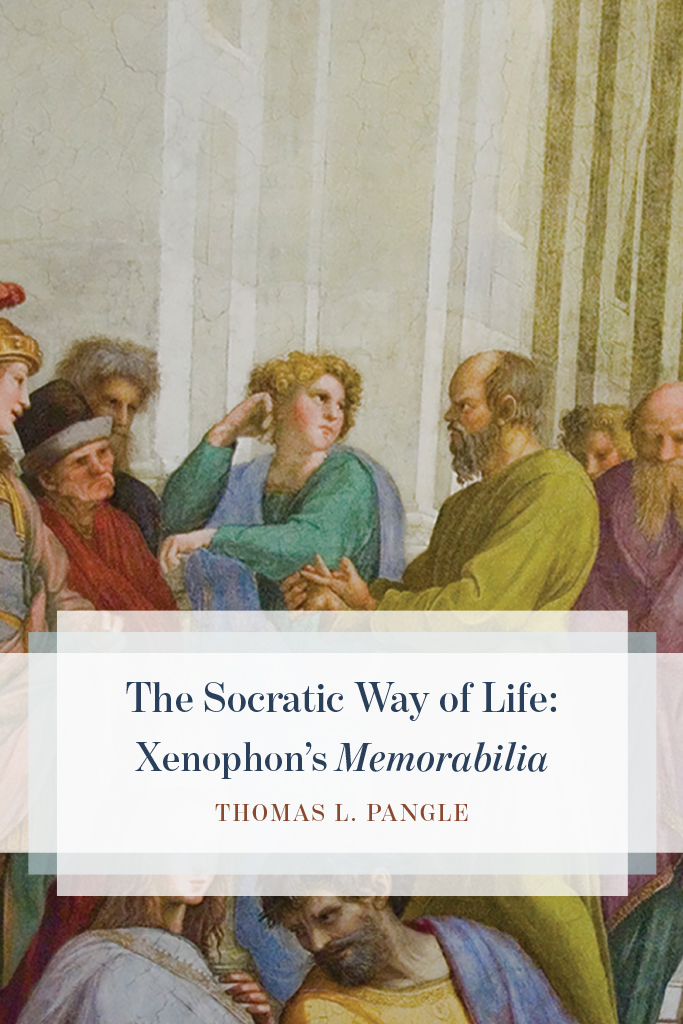

THE SOCRATIC WAY OF LIFE: XENOPHONS MEMORABILIA

THE SOCRATIC WAY OF LIFE: XENOPHONS MEMORABILIA

THOMAS L. PANGLE

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-51689-9 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-51692-9 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226516929.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pangle, Thomas L., author.

Title: The Socratic way of life : Xenophons Memorabilia / Thomas L. Pangle.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017026964 | ISBN 9780226516899 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226516929 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH : Xenophon. Memorabilia. | Socrates. | Justice. | Philosophy, Ancient. | Political sciencePhilosophy.

Classification: LCC pa4494. M 6 P 36 2018 | DDC 183/.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017026964

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To My Daughters

Heather and Sophia

The Memorabilia of Xenophon give a really true picture, that is just as spiritually rich as was the model for the picture; one must, however, understand how to read this book. The philologists believe at bottom that Socrates has nothing to say to them, and therefore are bored by it. Others feel that this book points you to, and at the same time gives you, happiness.

Nietzsche, posthumous frag. 18 [47] (1876)

CONTENTS

that express the best condition of soul of the human being.

For todays readers, Nietzsches stress on the Xenophontic Socratess roguish trickery is particularly helpful. Nietzsche lifts the cloak of boy-scout-like earnestness

Yet Nietzsches appreciation for Xenophons roguishly wise Socrates does not lead Nietzsche to become Xenophontic-Socratic. The best condition of soul of the human being exemplified in Xenophons Socrates ultimately remains, for Nietzsche, human, all-too-human. Nietzsche has much greater cultural hopes for and from, he makes much greater cultural demands upon, the potentially super-human philosophic soul and its creative uniqueness.

The fact is, Nietzsches evocation of the Xenophontic Socrates as a model occurs in unusual authorial circumstances. At this stage in his life, Nietzsche This question, of the relative merit of peak ancient and modern conceptions of the philosophic life (and of that lifes proper relation to civic life), will hover over our study.

In following Xenophon and his portrait of Socrates, we shall remain for the most part in what Nietzsche calls the realm of the shadowy nearest things. Xenophons Socrates, unlike Nietzsche, finds in the wrestling with the perplexities found in the nearest and dearest prephilosophic opinions the essential source of liberationthe only path to an adequate answer to the most important question confronting human life: By what standards ought one to live? Reasons attempt to answer this question encounters its biggest challenge in the widespread human testimonies to revelations of supreme commandments from mysterious, suprarational, providential divinity (cf. 1.4.1516).from a perspective that conceives the critical study of moral opinions and human psychology as the key to unraveling the universes greatest mystery. Xenophon indicates that for Socrates, perplexity about piety and impiety is closely connected with perplexity about the noble and the base, the just and the unjust, virtue and vice, and skilled political rule. This points us to the crucial distinction between Socratic philosophizing and Nietzschean philosophizingnay, between Socratic philosophizing and modern philosophizing as a whole.

As Nietzsche is acutely aware, the Socrates of both Plato and Xenophon takes piety so seriously that Socrates comes to sight as a divine missionarythough with a perceptible whiff of Attic irony and a delight in jesting.

This vast project of Nietzsches may be viewed as the fullest development of the enterprise uniting all the philosophers who, since Machiavelli, have broken with classical (Socratic) philosophy. Modern philosophy as such has been dedicated to taking over, and reshaping, by rationalizing, humanitys culturethereby mastering by eliminating the anti- or suprarational theological challenge. Through Xenophons Socratic writings we are given precious access to the character and way of life of the philosopher who is the fountainhead and paradigm of the alternative, premodern political rationalism, and its radically different, far less ambitious, response to the challenge of suprarational revelation.

Xenophon makes it obvious that Socrates does not seek to revolutionize the pious, participatory-republican culture that environs him. Rather, As a result, the Socratics inevitably attract moral and religious suspicion. Socrates strives, through his art of rhetoric, to dispel or to mitigate this distrust, and to prevent potentially subversive political consequences that might flow from his critical questioning. Eventually, however, the Athenian democracy indicts, convicts, and executes Socrates for impiety and corruption of the young. This sad outcome evidently does not come as a surprise to Socrates. He declares, as the day of his trial approaches, that throughout his life he has been concerned with, and preparing, his defense (4.8.4). And in Xenophons Apology of Socrates to the Jury, Socratess defense speech in court succeeds just as he has planned: not in preventing his execution, but in turning that execution into a kind of martyrdom that was to contribute crucially to a lasting defensive legacy for Socratic philosophizing.

Yet Socratess own lifelong self-defense, and then his courtroom speech, were not in themselves enough to bequeath a sufficiently accurate, while sufficiently protective, legacy of access to Socratic thinking and living. Needed in addition were the complementary writings of Plato and Xenophon, Socratess two greatest and closest students. Xenophon left it to Plato to construct a poetically sublime and even quasi-religious version of the more scientific and metaphysical dimensions of Socratic thought and life. Xenophon for the most part even left to Plato the portrayal of Socratic refutative dialogues focused on the What is... questions. Xenophon chose to continue, and to perfect as literature, the dimension of Socratic rhetoric that combines piously and moralistically defensive edification with subtle and often humorous provocation to questioning thought about the foundational opinions that govern prephilosophic human existence.

The Memorabilia, the longest and deservedly most popular of Xenophons four Socratic writings, is divided into two parts of very unequal length: in the first, Xenophon rebuts the charges of injustice in the official indictment brought against Socrates; then in the second, he explicitly transitions to a much longer account of how Socrates seemed to benefit those who had intercourse with him (1.3.1). As is made more evident in the conclusion to the whole work, the unifying focus is thus on defending the memory of Socrates by demonstrating his virtue of

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).