For Marina

1

An inscription over the door, to show what kind of a Book this is

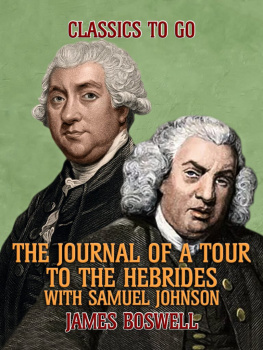

A scrap of land, a speck in the seas breath. On an October evening, a Tuesday, two travellers arrive after dark. The sea has been rough, and their crafts four oarsmen can find no easy place to disembark; it seems they must carry the visitors to dry land, though one of them chooses to spring into the water and wade ashore. In the moonlight the two figures embrace. It is late to be inspecting monuments, so they retire for the night sleeping fully clothed in a barn, nestled in the hay, using their bags as pillows.

The next day they explore the island. Its buildings have been battered by storms and stripped by locals needing materials for their homes; now they are ruins, caked in filth. The old nunnery is a garden of weeds, and the chapel adjoining it a cowshed. The two men walk along a broken causeway once a street flanked by good houses and arrive at the roofless abbey. Its altar is damaged; islanders have carried off chunks of the white marble, believing that they afford protection against fire and shipwreck. A few intricately carved stone crosses still stand.

Later, the visitors will write about what they saw. One will comment that the island used to be the metropolis of learning and piety and wonder if it may be sometime again the instructress of the Western Regions. The other will reflect that the solemn scenes of piety never lose their sanctity and influence: I hoped that, ever after having been in this holy place, I should maintain an exemplary conduct. One has a strange propensity to fix upon some point of time from whence a better course of life may begin.

This is a sketch of Iona, where in AD 563 the energetic Irish exile St Columba founded a monastery. Today, the islands great sites have been restored and are often mobbed with day trippers a mix of Christian pilgrims and happy-snapping tourists. Yet in 1773, when Samuel Johnson and James Boswell visited, few people went there. It was Johnson who reflected on the islands lost role as the metropolis of learning and piety, recalling how, as he experienced its decay but also its tranquillity, he was transported into the past to a time when it was the luminary of the Caledonian regions, whence savage clans and roving barbarians derived the benefits of knowledge and the blessings of religion. This was a place where earth and heaven seemed only a fingers width apart. Somehow it cheered the soul.

Whatever withdraws us from the power of our senses, Johnson wrote, and makes the past, the distant, or the future predominate over the present, advances us in the dignity of thinking beings. This is a rallying cry, an appeal for historical understanding. He doesnt mean that we should refuse to live in the moment, ignoring the pith of the present to spend our lives dwelling on how idyllic the past was or how ambrosial the future might be. Instead he is arguing that we are dignified by our ability, through the operations of our minds, to transcend our circumstances, to reach beyond the merely local, to appreciate difference.

It is an insight typical of Samuel Johnson, a heroic thinker whose intelligence exerted itself in a startling number of directions. A poet and a novelist, a diarist and editor and translator, as well as the author of numerous prefaces and dedications, he produced the first really good dictionary of English, invented the genre of critical biography, and shaped the common understanding of what is meant by English literature. He would not have recognized the term Renaissance man; not until half a century after his death did English import the word Renaissance, and Renaissance man is a twentieth-century coinage. But that is what he was: an astonishing all-rounder. A great moralist and essayist, he also practised the virtues he preached.

Today Johnson is not an obvious role model, for we live in an age when anyone laying claim to that title is expected to be golden attractive and infallible. He wasnt the sort of person that modern media companies lionize. His Instagram feed would be wack. Diet tips? Forget it. Although his Twitter might deliver a bit more sizzle, hed be an infrequent tweeter, what with his lethargy and dejection. Yet he has a lot to say to us. For instance, about role models: Almost all absurdity of conduct arises from the imitation of those whom we cannot resemble. This is a maxim for the era of social media, if ever there was one. Not least because, inside the designer heels or sleek sports shoes, the golden idol has feet of clay. Humanity is flawed, and if we allow ourselves to believe that any specimen of it is wholly unblemished, we see only a persona, not the person. Glossy role models conceal reality from us, rather than helping us navigate it.

Seeking a better example of how to live, we might not be quick to choose someone with several gruesome features. But faults are part of our magic. A person is stitched together out of both charms and imperfections, and we can only be inspired really and deeply inspired by someone whose virtues cohabit with weaknesses.

Samuel Johnson was precisely such a person. His achievements made him famous a public figure who, in the words of his friend William Maxwell, took on the role of an oracle, whom everybody thought they had a right to visit and consult. Vividly present in his own writings, he appeared even more colourfully in what others wrote about him: imposing and unkempt, quirky yet robust, courageous in his honesty, a supporter of the neglected and the needy, cutting through the thickets of trumpery and going down into all the dark places of the soul.

His days were full of crisis and suffering. He spent countless weeks and even years lost in what he called the maze of indolence, worried that he could not exclude the black dog of depression (his words) from his home and his head. Dramatically, and alarmingly, he pictured himself suspended over the abyss of eternal perdition only by the thread of life. Much of the time, he regarded himself as a failure. His many difficulties meant he had to be an expert at finding ways to handle misery and pain. Not all of these were good: in the belief that it would ease his breathing, he was often bled, and he made use of opium, valerian and the sea onion known as squill (a diuretic, otherwise employed as rat poison). But he put greater faith in what seemed to him the most effective natural painkillers: humour and friendship.

It was the humour that I found especially appealing when I got to know him, at nineteen, through Boswells Life of Johnson. I had a vague awareness that he was famed for his wit, yet was surprised by what I found: not the dry superiority that frequently passes for bel esprit, but something more daring, a vibrant candour. Often, reading about Johnson, there was the simple pleasure of sampling his verve, as when he wrote to his great friend Hester Thrale, I received in the morning your magnificent fish, and in the afternoon your apology for not sending it. Sometimes he might raise a smile that was close to being a wince by squashing some fond notion or ambition, for instance informing Boswell, As to your History of Corsica, you have no materials which others have not, or may not have. You have, somehow or other, warmed your imagination... Mind your own affairs, and leave the Corsicans to theirs. But what I saw above all was his belief in the utility of humour as a social lubricant, and also as a means of negotiating the worlds incongruities and accessing the truth.