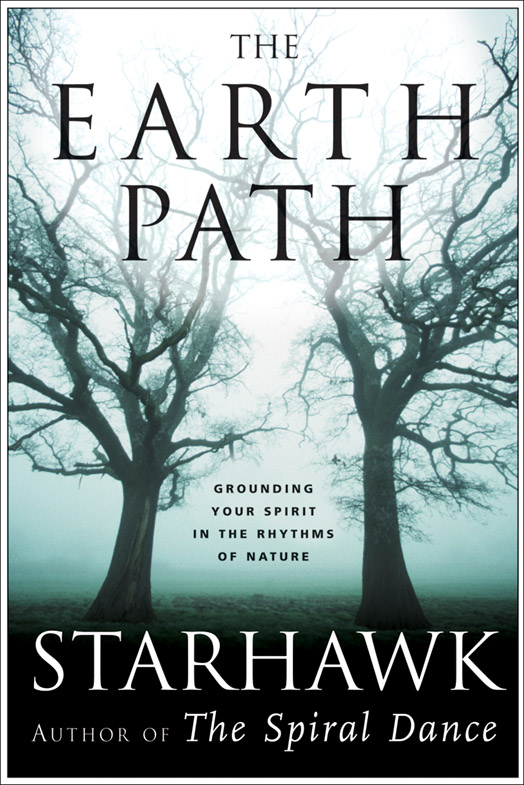

The Earth Path

Grounding Your Spirit

in the Rhythms of Nature

STARHAWK

Contents

THE SACRED

OBSERVATION

THE CIRCLE OF LIFE

AIR

FIRE

WATER

EARTH

THE CENTER

HEALING THE EARTH

On a hilltop in the coastal mountains of northern California, I meet with my neighbors just before sunset on a hot day in July to go to a fire protection ritual. All summer long, our land and homes are at risk for wildfire. In the winter, we get eighty to a hundred inches of rain in a good year, and trees and grasses and shrubs grow tall. But no rain falls from June through September, and in summer the land gets dry as tinder. A small spark from a mower, a carelessly tossed cigarette, a glass bottle full of water that acts as a magnifying lens can all be the beginning of an inferno that could claim our homes and lives.

We live with the constant risk of fire, and also with the knowledge that our land needs fire, craves fire. This land is a fire ecology. All the trees on it evolved in association with forest fires. The redwoods, with their thick, spongy bark, withstand fire. The madrones and bay laurels and tanoaks resprout from root crowns to survive fire. Fire once kept the meadows open, providing habitat for deer and their predators, coyote and cougar. Fire kept the underbrush down, favoring the big trees and reducing disease. The Pomo, the first people of this land, burned it regularly to keep it healthy. As a result, the forest floor was kept open, the fuel load was reduced, and fires were low and relatively cool. But now the woods are dense with shrubby regrowth, the grasses tall and dry. A fire today would not be cool and restorative, but a major inferno.

Below us is the small firehouse that belongs to our Volunteer Fire Department. We can look around to the far horizons and see our at-risk landscape. Deep canyons are filled with redwoods and Douglas firs, with bay laurel and madrone and vast stands of tanoak filling in the open spaces left where stands of giant conifers were logged a hundred years ago and, again, fifty years ago. The tanoaks are bushy, with multiple small stems that create a huge fire hazard. Big-leaf maples line the stream banks, and black oaks stud the open hillsides where fifty years ago sheep grazed. Tall stands of grasses in the open meadows are already dry and ready to burn. Once the meadows would have stayed green all summer with deep-rooted native bunchgrasses, but a century of grazing favored invasive European grasses that wither quickly in the summer heat. Small homes fill the wrinkles in the landscape, most built twenty years ago by back-to-the-landers out of local wood and scrounged materials. On the high ridges, we can see evidence of the latest change in land use, a proliferation of vineyards. Behind us is a huge fallen treea remnant of the 1978 wildfire that started just over the ridge and burned thousands of acres.

We begin by sharing some food, talking and laughing together, waiting for everyone to arrive. Then we ground, breathing deeply and with great gratitude the clean air that blows fresh from the ocean just a few ridges over. We imagine our roots going into the earth, feeling the jumble of rock formations and the volatile, shifting ground here just two ridges over from the San Andreas fault. We feel the fire of the liquid lava below our feet, and the suns fire burning hot above our heads.

We cast our circle by describing the boundaries of the land we wish to protectfrom the small town of Cazadero in the east to the rancheria of the Kashaya Pomo in the north; from the ocean in the west to the ridges and gulches to the south of us. We invoke the airthe actual breeze we can feel on our skin; the fire, so integral to this landscape yet so dangerous to us now; the water, the vast ocean now covered in a blanket of fog, the sweet springs that feed the land; the earth herself, these jumbled ridges and tall forests.

In the center of the circle is a small bowl. One by one, we bring water from our springs and pour it into the vessel. My neighbors know exactly where their water comes from. Each of us has spent many hours digging out springs, laying water pipes, fixing leaks.

This is from a spring beyond that hill that flows into Camper Creek that flows into Carson Creek that flows into MacKenzie Creek that flows into Sproul Creek that flows into the South Fork of the Gualala River

We offer the combined waters to the earth with a prayer of gratitudegreat gratitude that we live in one of the few places left on earth where we can drink springwater straight from the ground.

Alexandra has made our fire charma circle of bay laurel branches with a triangle lashed within. The triangle is the symbol of fire; the circle represents containment and also the cycle that we know someday needs to be restored. One by one, we come forward and tie on branches we have each brought from trees on our lands. Redwood, from a giant that has withstood many fires. Tanoak, suffering now from a fungal disease that fire might have cured. Madrone, of the beautiful peeling red bark, and buckeye in flower. They are as familiar as our human friends. We know them intimately, know when and how they flower and seed, have watched many individuals grow from seedlings. Some of my neighbors planted these hills after the 1978 fire, worked the creek beds to slow erosion, thinned and released the woods time after time. They know the boundaries of the soil types and the history of each patch of the woods. Ken and Alexandra bring small, uprooted firs, pulled out from a patch on their land where they grow far too thickly for any to get enough light to grow healthy and strong. Once fire would have thinned themnow people do. We add herbs and flowers from our gardens.

We pass the charm around, drumming and chanting to charge it:

Sacred fire that shapes this land,

Summer teacher, winter friend,

Protect us as we learn anew

To work, to heal, to live with you.

Green, green crown

Roots underground.

Kissed by fire,

Still growing higher.

Laughing, we dance with the charm, pass it over each others heads and bodies. These trees and branches are part of us as we have each become part of this land. The water we have brought is our drinking water, the water that grows our gardens. We literally eat and drink the land.

When the charm has gone around, we all hold it together and chant, raising a wordless cone of power, a prayer of protection, and also a prayer for knowledge. We pray that our homes and lives can be preserved as we struggle to learn, once again, how to integrate fire with this land, how to restore the balance that has been so lost.

Then the two young girls who are with us climb the fallen tree behind us and hang the charm high on its branches, where it will overlook the land for the summer. We will see it every time we look up at Firehouse Hill. And when winter comes, and the rain returns, we will take it down and cut it apart in our rain return ritual, where we thank the rain for coming back and pray for the health of the land and the trees. Well each take pieces of this charm to burn in our woodstoves for our winter fires, to protect our homes in the season when fire warms our hearths and cooks our food.