Disclaimer

Please note that the authors and publisher of this book are not responsible in any manner whatsoever for any injury that may result from practicing the techniques and/or following the instructions given within. Since the physical activities described herein may be too strenuous in nature for some readers to engage in safely, it is essential that a physician be consulted prior to training.

All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication, including illustrations, may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system (beyond that copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from Via Media Publishing Company.

Warning: Any unauthorized act in relation to a copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution.

Copyright 2017

by Via Media Publishing Company

Articles in this anthology were originally published in the Journal of Asian Martial Arts, and from Asian Marital Arts: Constructive Thoughts & Practical Applications (2013) Listed according to the table of contents for this anthology:

Seckler, J. (1992), Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 70-83

Taylor, K. (1993), Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 36-63

Suino, N. (1994), Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 84-91

Taylor, K. (1996), Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 80-89

Taylor, K. (1997), Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 80-103

Galas, M. (1997), Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 20-47

Babin, M. (2000), Vol. 9 No. 4, pp. 36-51

Svinth, J. (2002), Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 30-39

Suino, N. (2006), Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 22-29

Bryant, A. (2009), Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 64-71

Klens-Bigman, D. (2013), Asian Marital Arts , pp. 91-94

Taylor, K. (2013), Asian Marital Arts , pp. 133-136

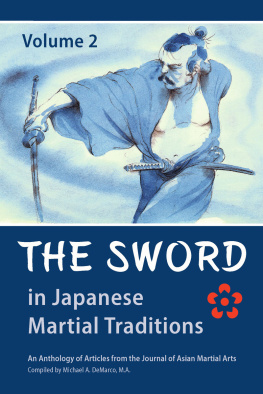

Cover illustration

Magical artwork by Oscar Ratti, created directly from his feel for the Japanese fighting arts and a lifetime of academic research and budo practice.

Futuro Designs and Publications

ISBN-13: 978-1893765481

ISBN-10: 1893765482

www.viamediapublishing.com

contents

by Michael DeMarco, M.A.

CHAPTERS

by Jonathan Seckler, B.A.

by Kimberley Taylor, M.Sc.

by Nicklaus Suino, M.A.

by Kimberley Taylor, M.Sc.

by Kimberley Taylor, M.Sc. and Goyo Ohmi

preface

If the Way of the warrior is the soul of Japan, their magnificent swords were the tools utilized to form the nation and forge their spirit. Youll find an abundance of information in this special two-part digital anthology in support of this thesis.

Kimberley Taylor wrote four chapters, the first being an interview with 7thdan Matsuo Haruna. Haruna offers great advice for practitioners based on his firsthand experience. Taylors two highly researched chapters give overviews of two major iaido schools. Excellent photos and descriptions of katas accompany the text. Taylors finale is a short piece describing two of his favorite techniques, while Deborah Klens-Bigmans chapter deals with two of her favorite techniques.

Another top ranking swordsman, Nicklaus Suino, gets to the finicky details of sword-drawing techniques as performed by masters. From his two chapters, we learn how to watch for telltale signs of expertise and come to a greater appreciation of the art of drawing the sword.

Jonathan Secklers chapter translates and comments on an essay written by Chozanshi Shissai in 1729. He argues that Neo-Confucianism rather than Zen became the foundation of swordsmanship, and illustrates how the sword arts began to be appreciated for their use for self-development.

Andrew Bryants chapter focuses on poems passed down within the Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu School of Iaido. These poems correspond to techniques contained within the system created in the 17th century. The author presents each poem and offers provides textual descriptions of their corresponding applications with each sword technique illustrated.

Joseph Svinths research presents the earliest kendo clubs to form in Canada. The socio-cultural settings add much flavor to this chapter. Information is provided regarding notable instructors, training, and competitions. Another way to better understand a martial tradition of one country is to compare it with another. Matthew Galas compares and contrasts sword arts in Germany with the Japanese traditions. The focus is on general principles and combat philosophy.

Devotees to sword practice are well award that scabbards get damaged. Michael Babins chapter shows how to build a serviceable scabbard according talents of anyone moderately handy with tools.

The twelve chapters described above should inspire further research and practice in the Japanese sword arts, plus bring a greater appreciation for their unique place in world history and culture.

Michael A. DeMarco, Publisher

Santa Fe, New Mexico, December 2017

Swordsmanship and Neo-Confucianism: The Tengus Art

Commentary and Translation by Jonathan Seckler, B.A.

Having no means of crossing this life,

I make swordsmanship my hiding place,

Sadly relying on it.

Good to make it a hiding place

Swordsmanship has no use for fighting over things.

These two doka by Yagyu Muneyoshi (1529-1606), the father of Yagyu Munenori, illustrate the attitudes of the samurai about swordsmanship in the Tokugawa period. Muneyoshi believed that swordsmanship need not be practical, an unusual idea prior to the seventeenth century. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, many samurai felt the same way. They began to view swordsmanship romantically, seeing it as a way to enlightenment and to enrich ones life, like practicing the tea ceremony, calligraphy, or studying Noh dance or chanting.

Hiroaki Sato notes that the Fudochi Shinmyoroku , a letter to Munenori from the Zen priest, Takuan (1573-1645), was widely regarded as a bible by practitioners of the martial arts during the Tokugawa period. The letter compares Zen to swordsmanship and claims that there are inexplicable links between the two.

Undeniably, many points of similarity can be found between Zen and swordsmanship. The same can be (and has been) said, however, of Zen and archery, Zen and the tea ceremony, and even Zen and writing! The fact is that Zen, with its emphasis on practice, concentration, and introspection, is compatible with an infinite number of activities. The link between Zen and swordsmanship is especially known in Japan, where many people are familiar with the saying, kenzen ichi (The sword and Zen are one). As G. Cameron Hurst points out, though, there is not necessarily a connection between the two. Indeed, few samurai warriors were believers in Zen.

It is too simplistic to say that the purpose of swordsmanship was to teach Zen, as it provided a vehicle to teach Neo-Confucian ethics as well. During the Tokugawa period, military subjects were stressed as part of the traditional educational curriculum, to the extent that in some instances half the day was spent on drill and training. Swordsmanship in this case was used as part of the educational process. Zen, on the other hand, is anti-intellectual, downplaying the value of education.