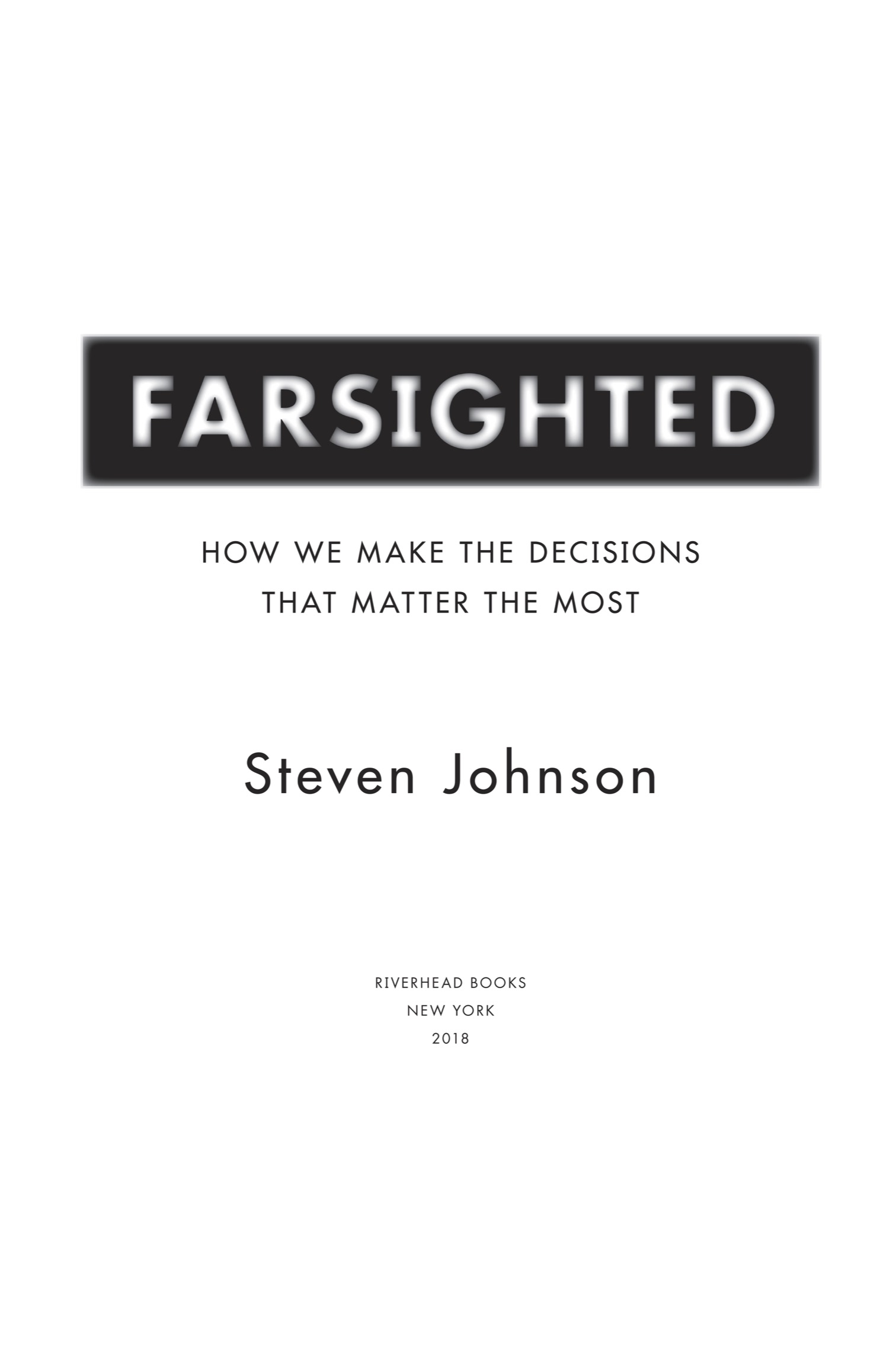

ALSO BY STEVEN JOHNSON

Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate

Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life

Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Todays Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter

The Ghost Map: The Story of Londons Most Terrifying Epidemicand How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World

The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America

Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation

Future Perfect: The Case for Progress in a Networked Age

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

R IVERHEAD B OOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Steven Johnson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Steven, author.

Title: Farsighted : how we make the decisions that matter the most / Steven Johnson.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017060305| ISBN 9781594488214 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525534709 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Decision making.

Classification: LCC BF448 .J64 2018 | DDC 153.8/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017060305

p. cm.

Version_1

For Dad

What theory or science is possible where the conditions and circumstances are unknown... and the active forces cannot be ascertained?... What science can there be in a matter in which, as in every practical matter, nothing can be determined and everything depends on innumerable conditions, the significance of which becomes manifest at a particular moment, and no one can tell when that moment will come?

L EO T OLSTOY , War and Peace

It is now clear that the elaborate organizations that human beings have constructed in the modern world to carry out the work of production and government can only be understood as machinery for coping with the limits of mans abilities to comprehend and compute in the face of complexity and uncertainty.

H ERBERT S IM ON

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MORAL ALGEBRA

Roughly ten thousand years ago, at the very end of the last Ice Age, a surge of glacial melt broke through a thin barrier of land that connected modern-day Brooklyn and Staten Island, creating the tidal strait now known as the Narrowsthe entrance to what would subsequently become one of the worlds great urban harbors, New York Bay. This geological event would prove to be both a curse and a blessing to the human beings who would subsequently live along the nearby shores. The opening to the sea was a great boon for maritime navigation, but it also allowed salt water to pour into the bay with each rising tide. Though Manhattan Island is famously bordered by two rivers, in reality, the names are misleading, since both the East River and the lower section of the Hudson are tidal estuaries, with extremely low concentrations of fresh water. The opening up of the Narrows made Manhattan Island a spectacular place to settle if you were looking for a safe harbor for your ships. But the fact that it was an island surrounded by salt water posed some real challenges if you were interested in staying hydrated, as humans are wont to do.

In the centuries before the completion of the epic aqueduct projects of the 1800s, which brought fresh drinking water to the city from rivers and reservoirs upstate, the residents of Manhattan Islandoriginally the Lenape tribes, then the early Dutch settlerssurvived amid the salty estuaries by drinking from a small lake near the southern tip of the island, just below modern-day Canal Street. It went by several names. The Dutch called it the Kalck; later it was known as Freshwater Pond. Today it is most commonly referred to as Collect Pond. Fed by underground springs, the pond emptied out into two streams, one of which meandered toward the East River, the other draining out westward into the Hudson. At high tide, the Lenape were said to have been able to cross the entire island by canoe.

Paintings from the early eighteenth century suggest that the Collect was a tranquil and scenic spot, an oasis for early Manhattanites who wished for an afternoons escape from the growing trade center to its south. An imposing bluffsometimes called Bayards Mount, sometimes Bunker Hillloomed over the northeast edge of the pond. Climbing the hundred feet of elevation that led to its summit opened up a spectacular vista of the pond and its surrounding wetlands, with the spires and chimneys of the bustling town in the distance. It was the grand resort in winter of our youth for skating, William Duer recalled in a memoir of early New York written in the nineteenth century, and nothing can exceed in brilliancy and animation the prospect it presented on a fine winter day, when the icy surface was alive in skaters darting in every direction with the swiftness of the wind.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, however, commercial development had begun to spoil the Collects bucolic setting. Tanneries set up shop on the edge of the pond, soaking the hides of animals in tannins (including poisonous chemicals from the hemlock tree) and then expelling their waste directly into the growing citys main supply of drinking water. The wetlands at the edge of the pond became a common dumping ground for dead animalsand even the occasional murder victim. In 1789, a group of concerned citizensand a handful of real estate speculatorsproposed expelling the tanneries and turning Collect Pond and the hills rising above into a public park. They hired the French architect and civil engineer Pierre Charles LEnfant, who would design Washington, DC, several years later. An early forerunner of the public-private partnerships that would ultimately lead to the renaissance of many Manhattan parks in the late twentieth century, LEnfants proposal suggested that Collect Pond Park be funded by real estate speculators buying property on the borders of the preserved public space. But the plan ultimately fell through, in large part because the projects advocates couldnt persuade the investment community that the city would ultimately expand that far north.

By 1798, the newspapers and pamphleteers were calling Collect Pond a shocking hole that attracted all the leakings, scrapings, scourings, pissings, and shittings for a great distance around. With the ponds water now too polluted to drink, the city decided it was better off filling the pond and the surrounding marshlands, and building a new luxury neighborhood on top of it, attracting well-to-do families who wished to live outside the tumult of the city, not unlike the suburban planned communities that would sprout up on Long Island and in New Jersey a hundred and fifty years later. In 1802, the Common Council decreed that Bunker Hill be flattened and the good and wholesome earth from the hill be used to erase Collect Pond from the map of New York. By 1812, the freshwater springs that had slaked the thirst of Manhattans residents for centuries had been buried belowground. No ordinary, surface-dwelling New Yorker has seen them since.