ABOUT THE AUTHORS

THOMAS CATHCART and DANIEL KLEIN studied philosophy together at Harvard in the last millennium. Since then...

Danny has written comedy for Lily Tomlin, Flip Wilson, and others, and published scores of fiction and nonfiction booksfrom thrillers to entertaining philosophical books, such as his London Times bestseller Travels with Epicurus and his most recent book, Every Time I Find the Meaning of Life, They Change It.

Tom studied theology and managed health care organizations before linking up with Danny to write Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar... , Aristotle and an Aardvark Go to Washington, and Heidegger and a Hippo Walk Through Those Pearly Gates. He is also the author of The Trolley Problem, or Would You Throw the Fat Guy Off the Bridge?, an entertaining philosophical look at a tricky ethical conundrum.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2018 by Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Permission credits for the use of cartoons appear on .

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Cathcart, Thomas, 1940 author.

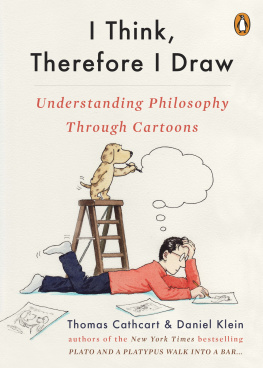

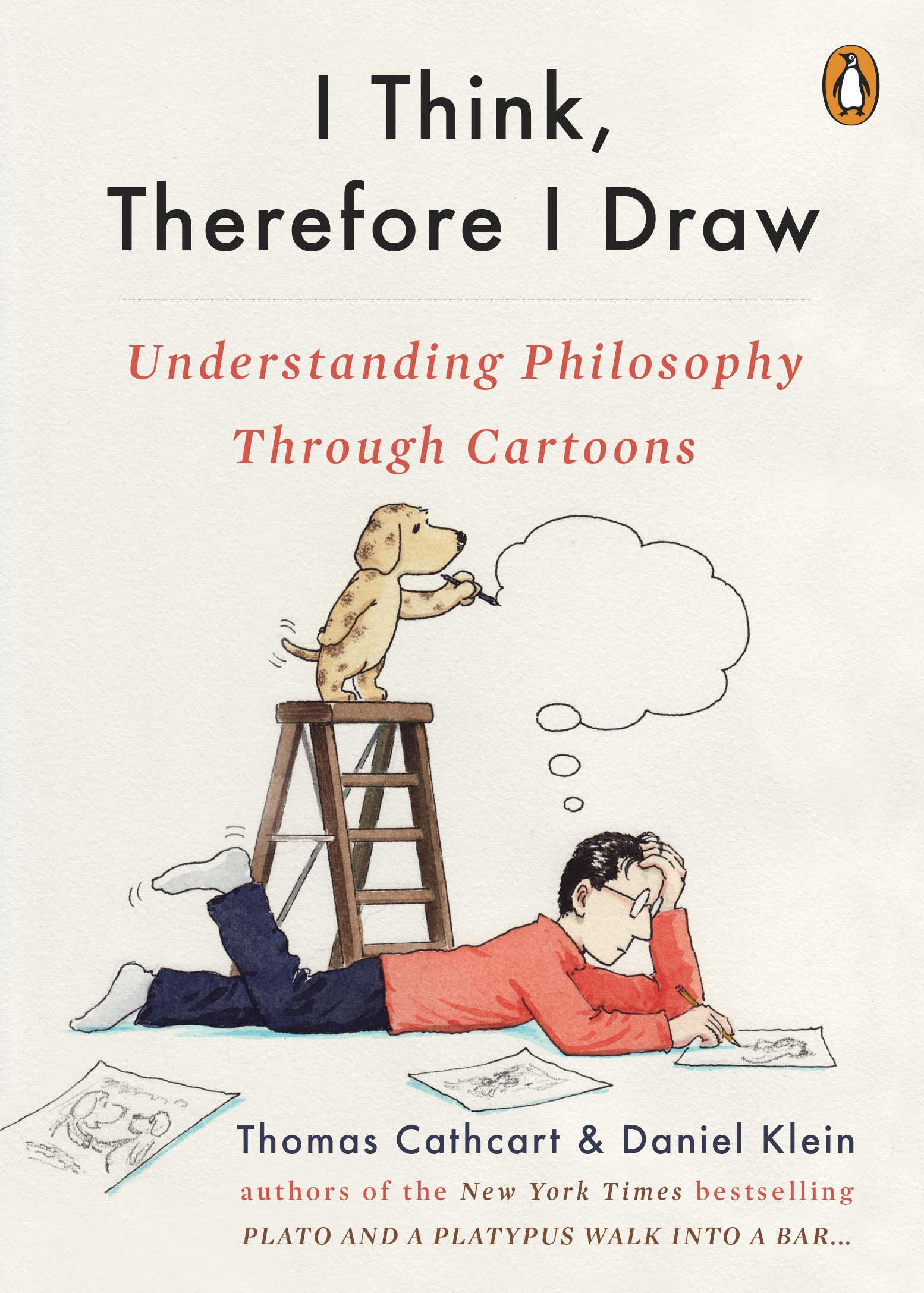

Title: I think, therefore I draw : understanding philosophy through cartoons / Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018018295 (print) | LCCN 2018031187 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525504856 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143133025 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: PhilosophyIntroductionsCaricatures and cartoons.

Classification: LCC BD21 (ebook) | LCC BD21 .C38 2018 (print) | DDC 102.2/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018018295s

Cover design: Paul Buckley

Cover illustration: Harry Bliss

Version_1

FOR JULIA LORD

I like physics, but I love cartoons.

THE LATE STEPHEN HAWKING, COSMOLOGIST

Contents

Introduction

Sure, we all know that the best cartoonists are keen observers of the state of our society, its quirks and ironies. We also know that some of their cartoons offer acute psychological and sociological insights. But what we often miss are the remarkable philosophical points the finest cartoonists make.

Like the best jokes, the best cartoons address philosophys Big Questions. They explain and illustrate these perennial conundrums and their various answers in ways that are sometimes ingenious, sometimes profound, and sometimes even a bit useful. Yup, these cartoons are incisive snapshots of the Biggies.

But where did these amazingly talented philosophical cartoonists come from?

Our hunch is that they are PhDs in philosophy who couldnt find employment or, if they could, found that serving lattes at Starbucks was less fulfilling than they had hoped. Then again, these PhDs may have gone the academic route and begun teaching a course in underdetermination and provability at a small liberal arts college, only to find themselves sinking into a deep depression that was relieved only by doodling in the margins of library books. Funny doodles.

As a result, we have been blessed with Nietzschean cartoonists, Aristotelian cartoonists, Sartrean, Russellian, Quinean, post-Kantian, and Marxist cartoonistseven cartoonists who understand what in hell Derrida was trying to say and are able to clue us in via a droll drawing and a witty caption.

Wittgenstein once said that a serious and good philosophical work could be written that consisted entirely of jokes. (He was not trying to be funny at the time.) Undoubtedly, if Wittgensteins subscription to Punch hadnt lapsed, he would have featured cartoons in his pronouncement.

Here, then, is a collection of our favorite philosophical cartoons and our annotations about what they teach us about the Big Questions in philosophy. Questions like, Is there really any difference between girls and boys? and Is there a cosmic scheme? and What went wrong with right and wrong? Eighteen of the most frequently asked questions in the history of philosophy.

Many of the cartoons are spot on topic, but a good number of them slip into the philosophical realm through the back door. At least, we think they slip in that waywe have been known to stretch a connection here and there when we whimsically get carried away. In these cases, we beg your indulgence.

Which brings us to the manner in which we have sequenced the Big Questions sections: by pure free association. Hope you dont have a problem with that.

I

Whats It All About, Alfie?

The Meaning of Life

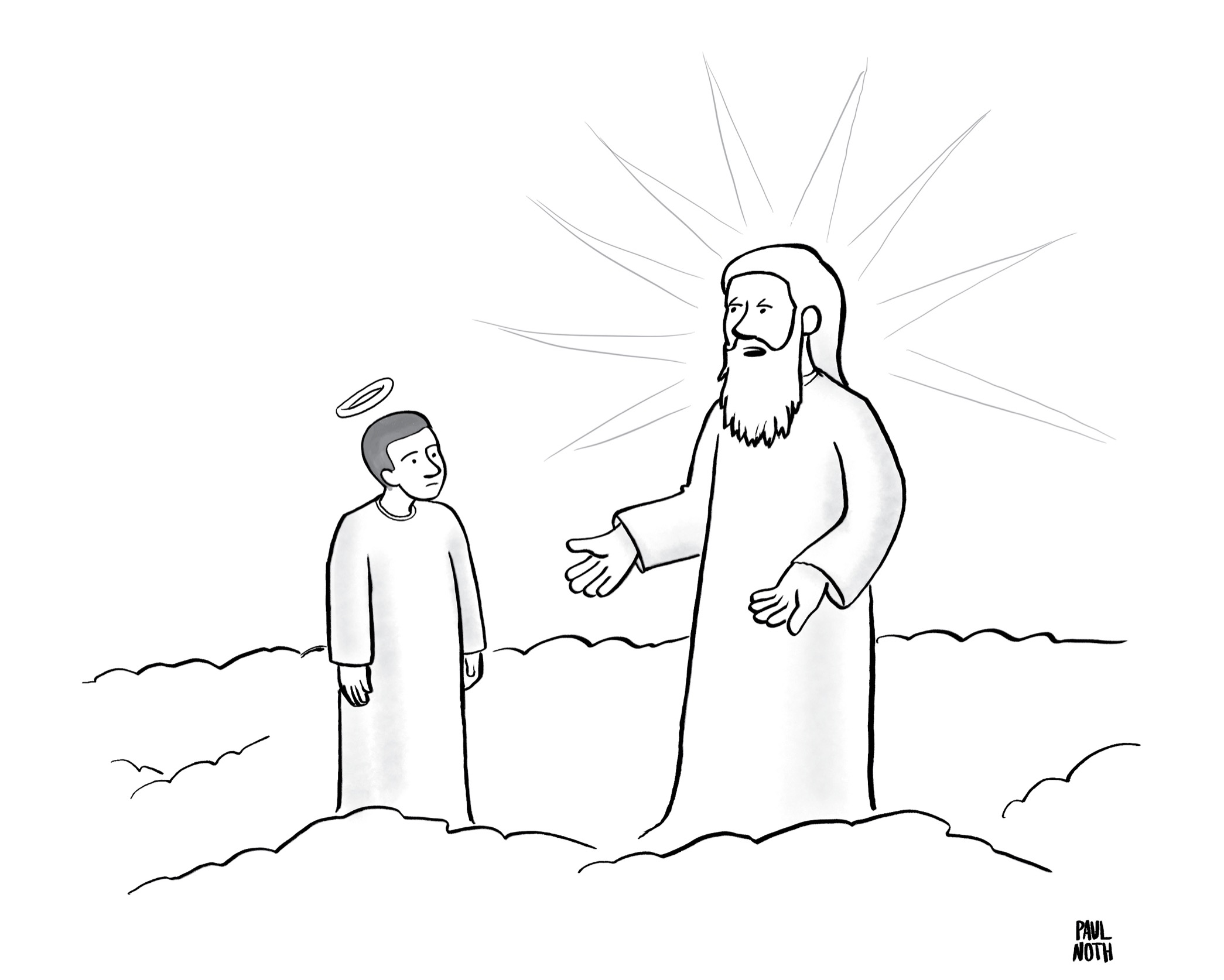

Look, if I have to explain the meaning of existence, then it isnt funny.

Is That All There Is?

There is nothing in the cosmos that gives us more pleasure than a cartoon that hits a philosophical idea right on the head. And this is one of them. In this cartoon, the prolific comedy writer and cartoonist Paul Noth pictures a God who not only embraces twentieth-century existentialisms absurdist point of view, he hopes to wring a few laughs out of it.

The question of the meaning of life is generally considered the biggest of the big philosophical questions. If there is no answer to this one, then asking any other philosophical questions seems kind of pointless.

Of course, in modern times, many analytic philosophers find the whole meaning-of-life question pretty silly. Hey, what is the meaning of meaning, bozo? they ask. Good question, although there is something unseemly about being called bozo by an analytic philosopher.

The twentieth-century existentialistsespecially Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Samuel Beckettconcluded that not only is life meaningless, its absurd. Its all one big Cosmic Gag. The kind where you choke laughing.

Sartre says we humans, unlike things, have no predetermined essence. There is no objective meaning to our lives, as there is to, say, an ashtray, which has a given reason to exist, namely, to hold ashes and butts. Of course, we could hold ashes and butts too, but for us it would be a choicethe choice to be a human ashtray. (You may be wondering why anyone would choose to be an ashtray. We arent naming any names, but we do know this one guywell call him Reggiewho chose to be a doormat.) But we could also choose to be something else: for example, a hippie or a tax lawyer. Sartre says thats because our existence precedes our essence. We arent handed lifes meaning, so its imperative that we choose it for ourselves.

Thats the downside of Sartres dictum, that we have to make a choice, even if we dont want to. So, on the one hand, were perfectly freegreat. But, on the other hand, we have no objective guidelines on how to use that freedomyikes! Who can say for sure whether its better to choose to be a hippie or a tax lawyer? And yet we must chooseand be responsible for that choice. Suddenly, we arent feeling so good.