1. Introduction: Protests in the Wake of the Great Recession

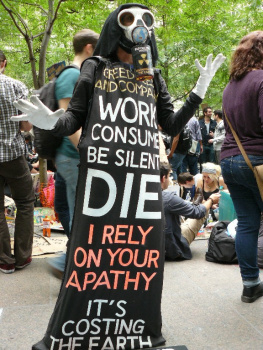

The election of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the USA came as a shock to most observers and commentators. As such, it was the (preliminary) culmination point of a decade of surprising events: In 2008, the bankruptcy of the investment bank Lehman Brothers precipitated the worst economic recession since the Great Depression. One year later, the Tea Party, an explosively growing, right-wing conservative protest mobilization, helped to dampen or to stop the reformist programs of the newly elected Obama administration and injected radical ambition into the Republican Party which many had already seen as being in inevitable decline after Obamas election. In 2011, just as the economic indicators seemed to suggest that the crisis was over, a group of young, left-wing activists, inspired by the uprisings around the Mediterranean, began a symbolic encampment in the heart of the financial district of New York City. After a short incubation period, Occupy Wall Street spread to cities all over the USA and many other countries, voicing sharp criticism of rising inequalities. In 2015, observers of the primaries of the two large US-American parties began to register signs of anomaly: In the Democratic Party, the social democrat and self-proclaimed socialist Bernie Sanders managed to win important primary elections against Hillary Clinton, who had already been considered the de facto crowned presidential candidate. The leadership of the Republican Party began to abandon their favorite candidate Jeb Bush and to support the so-called Tea Party candidates Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio as contenders against the rise of Donald Trumpas we know, ultimately in vain.

It is striking how similar the political public reacted to these events: Almost nobody saw them coming. Early signs were ignored and those that did warn about them were ridiculed or excluded from serious debates. When the dynamic of the event became undeniable, its scope was first talked down before the mood quickly turned: The events were now seen as unprecedented, tide turning, and teaching us all important lessons. And after their momentum faded, they were either forgotten or relegated to the dustbin of the anecdotic.

Freud theorized that the symptom is to be understood as the return of something repressed, and such a recurring surprise by seemingly random events nurtures the suspicion that there is something we avoid to confront and which therefore continues to haunt us. It is the wager of this book that this is indeed the case. There is something the public debate was avoiding to confront and which threatened to resurface in these moments of shock. And however fleeting their appearance and disappearance might have seemed, the protests of the Tea Party (TP) and Occupy Wall Street (OWS) offer a window into the social processing of the hard subjective and objective reality that subterraneously connects the Great Recession and the election of Donald Trumpand even points beyond it. The economic crisis was no black swan that interrupted the normal course of events out of the blue. Instead, it represented the escalation of deep economic imbalances rooted in the contradictions of the current state of global capitalism. In the same vein, these protests should not simply be reduced to a (more or less) consequential but ultimately random event. Rather, they should be seen as symptoms of the very crisis they reacted to, thereby revealing social tensions at the heart of contemporary capitalism. Given that the political economic contradictions that became visible as the Great Recession are far from resolved, it is all but surprising that the wishes, tensions, and grievances that drove these protests surfaced againand with force.

This book understands and analyzes the protests therefore as symptoms of an underlying socioeconomic crisis. Its guiding question , which will be further theoretically and methodologically nuanced and unfolded in the rest of this introduction, is: How can the lived experience of the Great Recession by the social classes that drove these mass protests be understood as shaping and informing their very protest-practice? Or, the other way around, how can the protests as a social practice be interpreted as a symptom of the socially specific lived experience of the political economic crisis?

To answer this question, I focus on the first, explosive phase of OWS and the TP. The aim is to analyze the respective protest-practices rootedness in the socially specific lived experiences of those that expressed their longings and discontents in them. I did not choose these examples because they effected or initiated important political changes, nor because I deem them politically more relevant than other protests in the same period of time. Instead, I chose them for two main reasons. First, pragmatically speaking, they were accessible to me. Thanks to generous funding provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (DFG), I was able to travel to the USA for three extended periods of field research. My experiences with both Leftist activism (especially of the college campus variety) and with interviewing conservative activists and personal ties provided an opportune combination that allowed me to quickly establish friendly and open relationships to people active in the TP and OWS. Drawing on Georg Simmels metaphor, it does not matter much from which point of the surface of a given moment we lower the lead (Simmel , 71)if we proceed carefully, it will start to swing with the same deep currents.

Second, beyond pragmatic considerations, it was the hopes and fears projected onto and articulated through them, and the diffuse and often contradictory claims and issues raised by them, that made me think of them as a promising starting point for sketching out the fault lines and discontents that built up with the escalation of social contradictions during this socioeconomic crisis. True, their constituencies were not among those objectively hit the hardest by the Great Recession. Yet, through mobilizing hundreds of thousands and being vocal about their discontents, they prove to be very sensitive indicators of the developments. Furthermore, the class-generational units from which the core constituencies of the respective protest mobilizations were drawnthe older cohorts of the classical petty bourgeoisie in the case of the TP and the younger, aspiring cohorts of the new petty bourgeoisie in the case of OWStend to be very involved in the processes of political opinion building in the USA. As important factions of the so-called middle classes, these groups importance for the legitimacy of the political system can hardly be overestimated. Their perceptions of the crisis and their criticisms must therefore be carefully interpretedindependent of the degree of legitimacy that one intuitively is willing to grant them.

At first I was, for example, irritated by the son of two philosophy professors, himself a student and scholarship-recipient in a prestigious graduate program at New York University, somewhat martially declaring that his generation was hit by the Great Recession with the force of a bomb and that he experienced wrenching periods of underemployment before he joined OWS (Gould-Wartofsky , 4). However, there is no denying that he and his fellow occupiers were the ones who articulated the most vocal criticism of rising social inequality and a general discontent about the way the crisis was politically and economically processed. Connecting the criticism to its social roots should therefore not be misunderstood as a veiled attempt at disqualification qua social reduction. Instead, connecting it to the social conditions of the possibility of its occurrence hopefully contributes to the overall potential of a critique of the very social conditions that underlie the suffering and the discontent driving the critique.