THE ULYSSES TRIALS

Beauty and Truth Meet the Law

Joseph M. Hassett

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Contents

Foreword by Roy Foster

Books register the ideas of an age; that is perhaps their chief claim to immortality. The statement by one of the heroines of this book, Margaret Anderson, might also be applied to the law: which, in key confrontations, can exemplify and clarify a historical moment. This is what happened when James Joyces great leviathan of a novel, destined to alter the course of literature, came up against the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and the US Post Office, which literally consigned Joyces text to the flames. The story has been told before, but never in the way it unfolds on these pages. This is because Joseph Hassett is both a gifted literary critic and a brilliant lawyer. In The Ulysses Trials he has succinctly and elegantly revised our understanding of what went wrong in the first trial of Ulysses , after Anderson and Jane Heap published extracts in their Little Review . And he also demonstrates, with forensic panache, the way it was put right.

Nor is this all. Hassetts previous books have dealt authoritatively with the life and work of W.B. Yeats, and this book provides an important addition to the biography of Yeatss friend and patron, the New York lawyer John Quinn. Subtle and often hilarious layers are added to the portrait of this irascible, talented, well-meaning but often obtuse Irish American, showing that his extraordinary ability to appreciate the coming vogue in art and literature was not always the same thing as understanding it. In this telling, Quinns own oddly puritanical prejudices, and his complicated attitude to sex and secrecy, infused and derailed his attempted defence of Anderson, Heap and Joyce. Hassetts evaluation is in marked contrast to previous treatments, and is powerfully bolstered by the authors knowledge not only of the law, but of the social mores and practices of the contemporary world of lawyers (and of Irish-Americans).

Here we are led deftly and enlighteningly through the nuanced definition by Judge Learned Hand of obscenity, the aesthetic and moral arguments advanced by the advocate Morris Ernst in the later trial involving Random House, and the complicated issues of copyright following the first publication of Ulysses by the redoubtable Sylvia Beach. But these arguments never become abstract or obtuse; Hassett has the exceptional lawyers gift of relating principles and precedents to real people and personal passions, and the astute literary critics ability to seize the thought behind an authors words. This matters all the more when we are dealing with a writer who opens the English language, in Seamus Heaneys words, like a pack of cards in the hands of a magician. Key Joycean passages are illuminated here, and the elusive figure of Shem the Penman, piercing the barrier between private and public, shown in a new though characteristic light.

Above all, this is a story of remarkable people: Anderson and Heap, ecstatically engaged on their mission of truth and beauty; John Butler Yeats, living merrily in New Yorks Bohemia at Quinns expense, while offering him unrecognized the key to arguing Joyces case, and concluding regretfully that the lawyer had brains but no intellect; his son, the poet W.B. Yeats, equally astutely noting his friend Quinns shortcomings, and sharply intuiting the real importance of his one-time protg Joyces great novel. But above all, the lawyers steal the show: from puritanical servants of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and colourful and sometimes dubious Irish Americans, to perceptive interpreters of the intellectual zeitgeist such as Woolsey and the Hand cousins judges of robust intellect and trenchant pen. Robustness and trenchancy are evident in every page of this book. Looking back on the saga much later, Learned Hand reflected that for a judge to be literary was a very dangerous thing: but danger could be averted if the judge in question was perceptive enough to exhibit a complete aptness for the occasion. Joseph Hassett evinces exactly this combination of literary insight and legal dexterity, which is what makes his book such an original and subtly entertaining contribution to the history of modernist culture.

Roy Foster

Carroll Professor of Irish History,

Hertford College, Oxford

Introduction

The struggle of writers to free themselves from government control over the content of their writing is never-ending. It is at least as old as Plato, who banished poets from his Republic because he thought their seductive verbal pictures harmed society. Oscar Wilde flatly challenged this line of thinking in his famous pronouncement that There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all. Platos ideas prevailed over Wildes in this round of the long struggle. Wilde was imprisoned and effectively banished following a prosecution that started out as an attack on his aesthetic ideas.

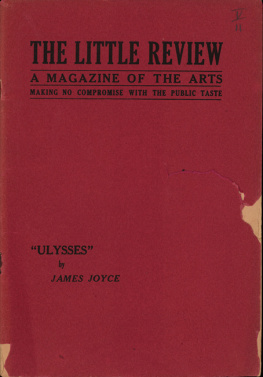

The law of obscenity figures prominently in the war between law and literature. An obscenity trial, to borrow Arthur Millers vivid metaphor, is a crucible for testing the relationship between these mighty cultural engines in which each confronts the other head-on. Literature, by its very existence, asserts a primal right to be heard. The law of obscenity seeks to silence a category of books and threatens to imprison their authors and publishers. Margaret Anderson, founder of The Little Review , and her lover and co-editor Jane Heap, faced just such a threat in 1921 in the form of a criminal trial for publishing an episode of James Joyces Ulysses . Heap saw the charges as an attack by the law on an eternal work of art. She maintained that Art is and always has been the supreme Order, and thus is the only human activity that has an eternal quality. Standing defiantly on this platform, she greeted her trial with the derisive exclamation: What legal genius to bring Law against Order! Heap and Anderson were convicted of a crime for being the first publishers of the immortal prose of what was ultimately recognized as the greatest English-language novel of the twentieth century.

Anderson and Heap urged their lawyer, John Quinn, to argue that Joyces prose could not be obscene because it was beautiful literature, and Quinns friend John Butler Yeats outlined an argument based on the societal value of Joyces terrible veracity. Unfortunately, Quinn, a man of enormous ability and generosity, but hobbled by a mind filled with prejudice and closed to opinions that differed from his own, failed to advance these potentially winning arguments. Instead he made a series of unworthy and cynical points addressed to what he chose to call the ignorance of the stupid judges. After his clients were convicted, he failed to seek an appellate ruling on the important legal issues presented by the criminalization of an innovative piece of writing by a master stylist. Thus Ulysses was silenced after the serialization of fourteen of the eighteen episodes contemplated by Joyce.

Although the powerful ideas urged on Quinn about the value of literatures beauty and truth never even made it to court in the 1921 Little Review trial, they ultimately prevailed a dozen years later when the completed novel faced obscenity charges in federal court in New York. Responding to arguments by a new lawyer that were similar to those that Quinn ignored, United States District Judge John Munro Woolsey found that Ulysses was not obscene because the American public should not be denied exposure to an honest effort by a great artist in words to show exactly how the minds of his characters operate. These federal decisions permanently altered the grounds of future obscenity trials in the United States and had significant repercussions elsewhere.