Introduction

Late in the afternoon of 8 November 2016, I stood with Lalit Jha, the Press Trust of Indias US representative, at the corner of 11th Avenue and 53rd Street, by the Hudson in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. We had to make a decision. Going down the 11th Avenue would take us to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Centre, where Hillary Clintons victory party was planned. Turning towards the 53rd would take us to the New York Hilton Midtown on 6th Avenue, which was Donald Trumps election night headquarters.

We turned on to the 53rd. After a full year of travelling extensively in America, a large part of it together, we were able to get that turn right. But when we reached the Trump headquarters, it bore a forlorn look. In the press room, long rows of workstations awaited occupants, and huge stacks of sandwich boxes were yearning to be picked up. In a few hours, though, the whole world would turn its attention there.

Earlier, on our drive from Washington DC to New York City, we had listened to Prime Minister Narendra Modis speech announcing demonetization.

* * *

It was on a Sunday afternoon in Delhi in 2015 that Malini Parthasarathy, The Hindus then editor and now co-chairperson of The Hindu Group, called to ask me if I could go to the US. I thought she was asking me to cover the UN General Assembly in September that year, where Prime Minister Modi was scheduled to appear. Yes, I said, readily. I mean, as our US correspondent, she explained, sensing that I was misreading the conversation. I sought a little time to think and discuss it with my wife.

A few days later I said yes, and soon found myself in America, wading into an election season that everyone in Washington DC had long passed a verdict on. No force on earth could beat the Clinton machinery, I heard from all around. Trump? He is a protest candidate. He wont survive the Super Tuesday. I googled protest candidate and Super Tuesday.

That November, in New Hampshire, I attended a Trump rally for the first time. When I heard him repeatedly referring to himself in the third person, I was struck by it. I knew I had heard this before. My first report on Modi was regarding his Gujarat campaign in 2007. The Indian Express front-page story was titled In 30 minutes, Modi names himself 29 times, BJP 6, and in slip asks: me as PM?

Trumps speeches through the 2016 election cycle seemed almost an American adaptation of Modis speeches throughout his political career. Both of them promised economic progress, employment, infrastructure, focus on military, a muscular foreign policy and, above all, the restoration of their nations glory. Modi termed his politics India First for the first time in an address to an American audience on 14 May 2013 that he could not deliver in person due to a travel ban.

Modi said Indias election commission was acting against him; illegal immigrants from Bangladesh were voting against his party. So he promised to deport them. But he was of the view that Hindus coming from other countries must be protected. Trump said illegal Mexicans were voting for the Democratic Party

The more I heard Trump, the more familiar the territory felt to me.

Modi is a self-declared former tea-seller who rose up the ladder of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Trump was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Modi worked all his life, attending RSS shakhas, travelling the length and breadth of the country, with little money and in simple clothesfor promoting the idea of a Hindu rashtra. Trump spent a lifetime partying and getting photographed with the rich and the powerful, a memorable picture among these being one with Bill and Hillary Clinton. He was part of the economic elite, though not of the cultural elite. But he knew what would sell in the electoral market and so he made a package and marketed it well.

Modi worked for a lifetime to create the political atmosphere that enabled his victory; Trump sensed the political atmosphere created by the so-called establishment politicians, launched a product of his own and captured the market. Trump did to American politics what Steve Jobs did to handhelds. If Jobs collected a host of pre-existing features and applications and packaged them together, Trump assembled existing social prejudices and real economic distress and sold it to the people at a premium, under the slogan Make America Great Again.

* * *

By 10 p.m. on 8 November 2016, reporters were rushing to the New York Hilton Midtown from the Javits Convention Centre. Trump had been elected President. My lead story on the Trump victory for The Hindu the next morning echoed the lead story I had written on Modis historic victory in May 2014. It was just the beginning.

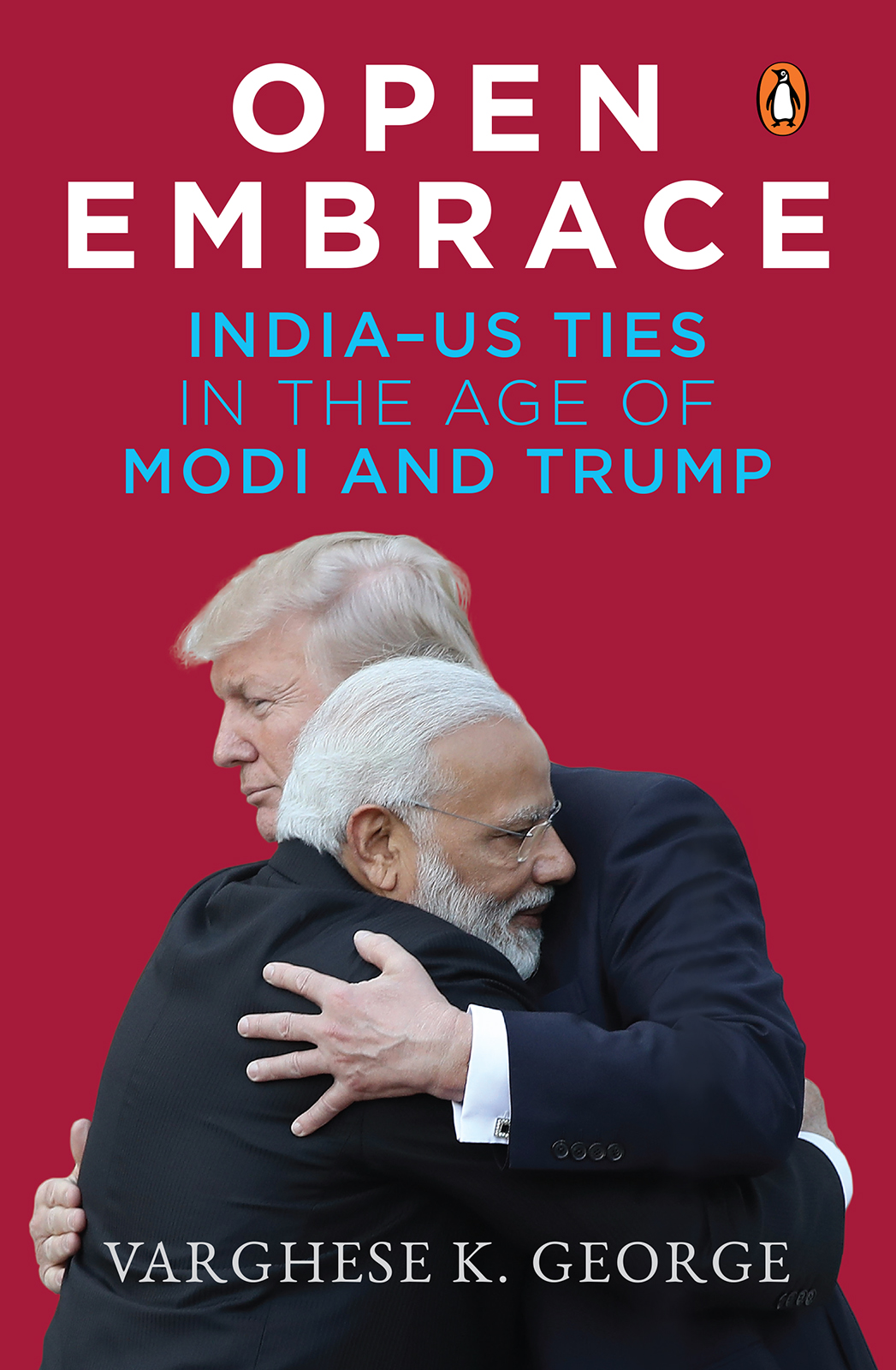

There has never been a dull day in Washington in the two years since then, as President Trump disrupted America and the world in significant ways. His self-admittedly unpredictable moves have impacted Indias strategic calculations as well. For Modi, it is India First; for Trump, it is America First. The question is whether they can find common ground. What happens to IndiaUS ties when both countries appear to be under the spell of ultranationalism? Or, in Trumpian language, can Modi and Trump make a deal? This book is a broad exploration of that question.

It is also important to note what this book is not. It is not a thesis on the strategic interests and calculations of the two countries, or on the technical questions related to military equipment and tactics, the minutiae of trade deals and disputes, or on geopolitics. There are highly eminent minds reflecting on such weighty matters, and there is no dearth of literature on them.

The scope of this book is to explore how two leaders, both driven by notions of nationalism, are reshaping their respective countries, and the impact of that process on their external ties. Open Embrace attempts to offer an unconventional approach to understanding strategy.

A word of gratitude is due to several people who stood by me through the writing of this book. Mukund Padmanabhan, editor of The Hindu, allowed me to pursue this plan. My colleagues at The Hindu have always been a great source of support. My special thanks to Suresh Nambath, P. Jacob, Amit Baruah, Suhasini Haidar, Mini Kapoor, Stanly Johny and Narayan Lakshman.

Shajahan Madampat gave greatly valuable suggestions on improving the structure and content; arguments with Seema Sirohi helped me shape my own views.

At Penguin, Swati Chopra put her trust in me and the book and greatly contributed to improving the manuscript, and Aditi Muraleedharan polished the text. Vandana Seth gave excellent research support and Kanishka Gupta served as a persistent literary agent. I am grateful to all.