1. Views of the Moon from the Past

For most of human history, the Moon has largely been a mystery. Cultures worldwide have long offered up myths to explain its existence. Some ancient peoples believed that the Moon was a rotating bowl of fire. Others thought it was a mirror that reflected Earths lands and seas. But philosophers in ancient Greece understood that the Moon is a sphere in orbit around Earth. They also knew that moonlight is reflected sunlight.

Some Greek philosophers believed that the Moon was a world much like Earth. In about A. D. 100, Plutarch even suggested that people lived on the Moon. The Greeks also apparently believed that the dark areas of the Moon were seas, while the bright regions were land.

Although Aristotles natural philosophy was very influential in the Greek world, it was not without competitors and skeptics. Thus, in his little book On the Face in the Moon s Orb , the Greek writer Plutarch (46120 CE) expressed rather different views on the relationship between the Moon and Earth. He suggested that the Moon had deep recesses in which the light of the Sun did not reach and that the spots were nothing but the shadows of rivers or deep chasms. He also entertained the possibility that the Moon was inhabited. In the following century, the Greek satirist Lucian (120180 CE) wrote of an imaginary trip to the Moon, which was inhabited, as were the Sun and Venus.

In about A. D. 150 Ptolemy, a Greek astronomer who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, said that the Moon was Earths nearest neighbor in space. He thought that both the Moon and the Sun orbited Earth. Ptolemys views survived for more than 1300 years.

But by the early 1500s, the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus had developed the correct viewEarth and the other planets revolve around the Sun, and the Moon orbits Earth.

The Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo wrote the first scientific description of the Moon, based on his observations with a telescope. In 1609, Galileo described a rough, mountainous surface. This description was quite different from what was commonly believedthat the Moon was smooth. Galileo noted that the light regions were rough and hilly and the dark regions were smoother plains. Galileo even sketched the Moon! (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.1

Galileos sketch of the Moon as he saw it through his telescope. From Galileos Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger). 1610

The presence of high mountains on the Moon fascinated Galileo. His detailed description of a large crater in the central highlandsprobably Albategniusbegan 350 years of controversy and debate about the origin of the holes on the Moon.

The medieval followers of Aristotle, first in the Islamic world and then in Christian Europe, tried to make sense of the lunar spots in Aristotelian terms. Various possibilities were entertained. It had already been suggested in antiquity that the Moon was a perfect mirror and that its markings were reflections of earthly features, but this explanation was easily dismissed because the face of the Moon never changes as it moves around Earth. Perhaps there were vapors between the Sun and the Moon, so that the images were actually contained in the Suns incident light and thus reflected to Earth. The explanation that finally became standard was that there were variations of density in the Moon that caused this otherwise perfectly spherical body to appear the way it does. The perfection of the Moon, and therefore the heavens, was thus preserved.

It is a curious fact that although many symbolic images of the Moon survive in medieval and Renaissance works of art (usually a crescent), virtually no one bothered to represent the Moon with its spots the way it actually appeared. We only have a few rough sketches in the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci (ca. 1500) and a drawing of the naked-eye Moon by the English physician William Gilbert. None of these drawings found its way into print until well after the telescope had come into astronomy (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.2

In 1645, the Dutch engineer and astronomer Michael Florent van Langren, also known as Langrenus, published a map that gave names to the surface features of the Moon, mostly its craters. Of the 325 names that he gave to lunar features, only a handful have been retained ( Source : Plenilunii lumina Austriaca Philippica , Brussels)

Astronomers of the 1600s mapped and cataloged every surface feature they could see. Increasingly powerful telescopes led to more detailed records. In 1645, the Dutch engineer and astronomer Michael Florent van Langren, published a map that gave names to the surface features of the Moon. A map drawn by the Bohemian-born Italian astronomer Anton M. S. de Rheita in 1645 correctly depicted the bright ray systems of the craters Tycho and Copernicus. Another effort, by the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in 1647, included the Moons libration zones.

By 1651, two Jesuit scholars from Italy, the astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli and the mathematician and physicist Francesco M. Grimaldi, had completed a map of the Moon. That map established the naming system for lunar features that is still in use today.

It was widely believed in the 1800s that the Moon was inhabited. This fantasy was supported by the discovery of what was thought to be a lunar city by the famed Bavarian observer Franz von Paula Gruithuisen. He observed a regular herringbone pattern of ridges arranged with geometric precision in the rough terrain to the north of Schrter Crater near Sinus Aestuum. Gruithuisen immediately interpreted this small landscape (which he called Wallwerk) as artificial structures that he saw as evidence of intelligent life. This interpretation was later dismissed, with the ridges being seen as a natural landform, causing Gruithuisen to lose face (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.3

Gruithisens drawings of his Wallwerk lunar city, including star temple on right, which he regarded as a colossal monument erected by inhabitants of the Moon (From Gruithisens observations made on July 12, 1822, in Bavaria)

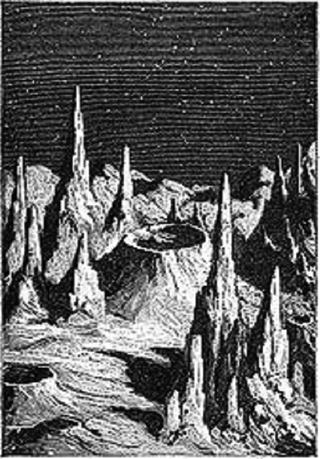

Until the late 1800s, most astronomers thought that volcanism formed the craters of the Moon. In the 1870s, the English astronomer Richard A. Proctor proposed correctly that the craters resulted from the collision of solid objects with the Moon. But at first, few scientists accepted Proctors proposal. Most astronomers thought that the Moons craters must be volcanic in origin because no one had yet described a crater on Earth as an impact crater, but scientists had found dozens of obviously volcanic craters (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.4

From the book Recreations in Astronomy by H. D. Warren, D. D., published in 1879. The figure was named Lunar Day, and it represents an historical concept of the lunar surface appearance. Robotic missions to the Moon later demonstrated that the surface features are much more rounded due to a long history of impacts (Illustration courtesy of Henry Warren. Used with permission)