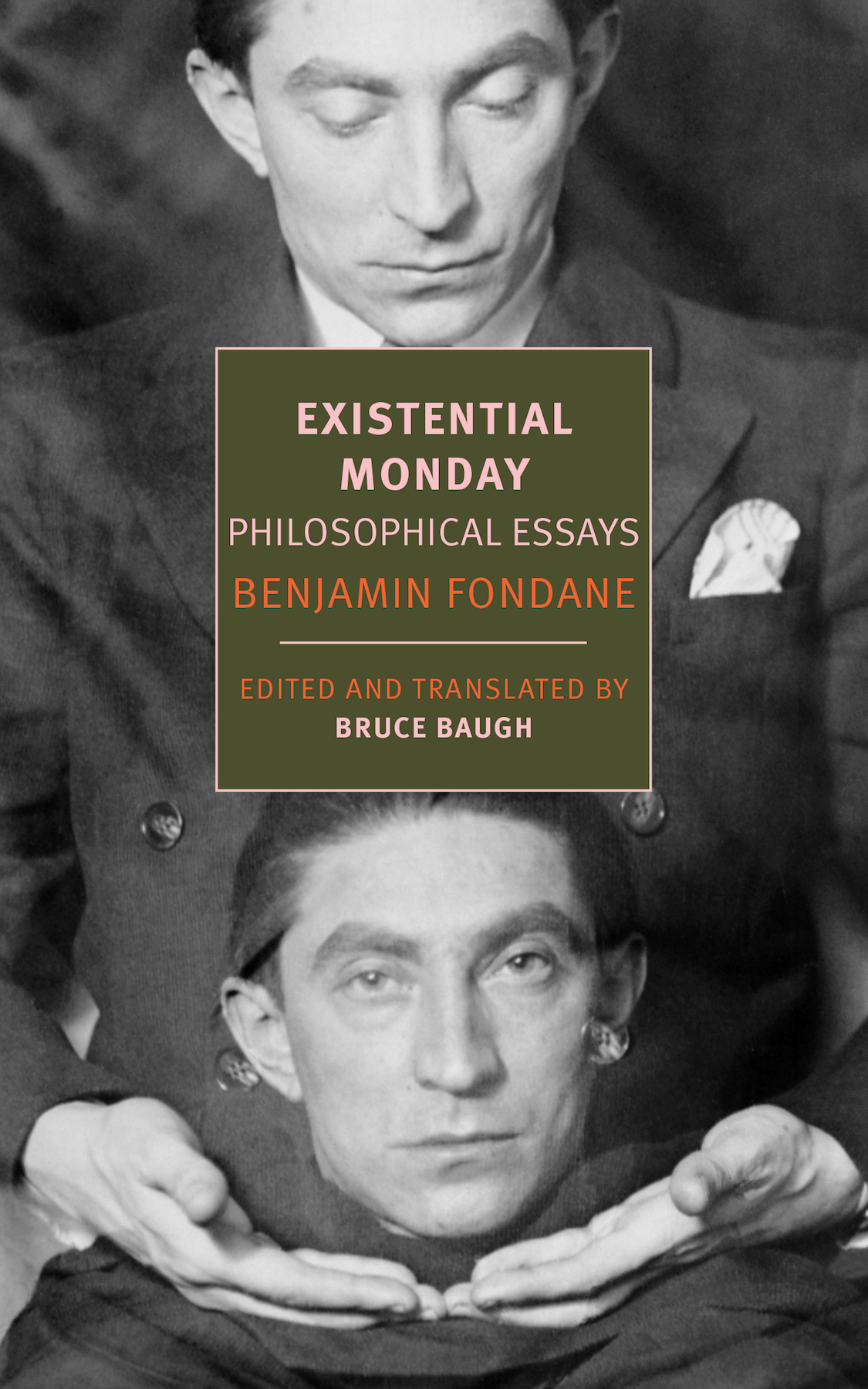

BENJAMIN FONDANE (18981944) was a Romanian Jew who emigrated to France in 1923 to pursue his love of French poetry and culture. While at law school in Bucharest, he spent most of his time writing for avant-garde literary periodicals. In Paris, Fondane worked at an insurance company and for Paramount Pictures while establishing himself as a poet and philosopher writing in French. Under the guidance of the Russian migr philosopher Lev Shestov, Fondane became a leading exponent of existential philosophy in the 1930s. He also spent time in Argentina, at the invitation of Victoria Ocampo, lecturing on avant-garde film and directing a surrealist comedic film. In 1944, he was deported from France and killed at Auschwitz. In addition to Existential Monday, New York Review Books publishes a volume of his selected poetry, Cinepoems and Others.

BRUCE BAUGH is the author of French Hegel: From Surrealism to Postmodernism and numerous articles on Benjamin Fondane, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-Paul Sartre, and other thinkers. An executive editor of Sartre Studies International from 2005 to 2015, he is currently a professor of philosophy at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia, where he specializes in twentieth-century French thought.

EXISTENTIAL MONDAY

Philosophical Essays

BENJAMIN FONDANE

Translated from the French and edited by

BRUCE BAUGH

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Original texts copyright 2016 by Michel Carassou

Translation, introduction, and notes copyright 2016 by Bruce Baugh;

copyright in the translation to Man Before History is shared with Andrew Rubens

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Man Ray, Benjamin Fondane, c. 1925

Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris / Telimage, 2014

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fondane, Benjamin, 18981944. | Baugh, Bruce, editor, translator. | Fondane, Benjamin, 18981944. Lundi existentiel. Selections. English. Title:

Existential Monday / by Benjamin Fondane ; edited, translated, and introduced by Bruce Baugh.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, 2016. | Series: New York Review Books classics | Translations of selections from Fondanes various philosophical works, including Lundi existentiel (Publishers information).

Identifiers: LCCN 2015028859 | ISBN 9781590178980 (paperback) Subjects:

LCSH: Existentialism. | BISAC: PHILOSOPHY / Essays. |

PHILOSOPHY / Political. | PHILOSOPHY / Movements / Existentialism.

Classification: LCC B819 .F56 2016 | DDC 194dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015028859

ISBN 978-1-59017-899-7

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T HE HISTORIAN Martin Stanton has called Benjamin Fondane surely the most underrated intellectual of the 1930s. During his life, he constantly crossed geographical borders, just as in his work he crossed the borders between genres and disciplines, ranging over poetry, theater, literary criticism, and philosophy. This very versatility may be the major reason that his philosophy remains so underappreciated.

Fondanes refusal to remain within the confines of any school or doctrine makes him unique, even within the context of the existential philosophy of which he was a leading exponent in the 1930s. A metaphysical anarchist, as the literature scholar Olivier Salazar-Ferrer has called him, so too was Fondane.

In the 1930s and 40s, Fondane was a major participant in the philosophical debates that were taking place among Marxists, Catholics and Protestants, surrealists and existentialists in a Paris that included a large number of migr intellectuals. And though his independence of mind and refusal to be limited by any doctrine made him an essentially solitary thinker, he was also an intarissable conversationalist who loved dialogue, argument, and polemic, right up until his final days in Auschwitz.

Fondane was a paradoxical character, and paradox is central to his philosophy: a vision of the solitary individual who through solidarity with other solitary individuals, in virtue of their common uniqueness, reaches towards a new sort of community, constituted through difference and individuality rather than the generalities of ideology, race, nationality, or religion, united by not belonging: un tas de SEULS (so many ALONES). Private thinkersSren Kierkegaard, Blaise Pascal, Friedrich Nietzsche, Lev Shestov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, united only in their being exceptionsthese above all constituted Fondanes community. His paradoxes and his contradictions, in his thought and in his life, create a barrier to those who seek a rationally coherent and unified body of work, but this very refusal of limits and categoriesthis revoltconstitutes both Fondanes singularity and the guiding thread that runs through all his works.

Benjamin Fondane was born Benjamin Wechsler near Iasi in the Moldavian province of Romania in 1898, the child of a moderately prosperous Jewish Romanian family. At the time, Jews made up nearly forty percent of Iasis population of around a hundred thousand; the town was a vibrant cultural center, having been the capital of an independent Moldavia until Moldavias incorporation into Romania in 1862. Fondane was fourteen when he published his first poems under the pseudonym I. G. Ofrir, and that year he went through several other pseudonyms before eventually settling on Benjamin Fundoianu (Fundoianu was the name of a country property belonging to his paternal grandfather). He moved to Bucharest to finish high school and then, at the behest of his family, studied law, but he spent most of his time writing articles and poetry for avant-garde Romanian periodicals and writing and directing plays for a short-lived theater company called Insula (The Island) that he founded with friends. Their anti-commercial, modernist productions shocked the bourgeoisie. Fundoianu, the poet, critic, essayist, and playwright, soon became a prominent member of the Romanian literary avant-garde; he was, in the words of a contemporary, the stooping green-eyed youth from Iasi, the standard-bearer of the iconoclasts and the new generation, around whom all those euphoric young men believing that they had something to say circled like moths around a flame.

But his heart lay elsewhere. Fondanes great passion was French poetry. In Imagini si Carti din Franta (Images and Books of France), a study of Stphane Mallarm, Andr Gide, Marcel Proust, and other French writers that he published in Bucharest in 1922, he writes: I have not come to know French literature as I might know German literature: I have lived it. Romanian literature, indeed, was merely a colony of French culture. Why not, then, seek French culture on its native soil? Like his compatriot Tristan Tzarasoon to be his friendFondane set his sights westward, in search of the most radical literary and philosophical ideas.

And like Tzara, Fondane arrived in the West in full revolt against rationalism and the reign of logic. Tzaras famous Dada Manifesto of 1918 declared: I am against action, for continuous contradictions, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense. Tzara continued: Logic is always wrong.... Its chains kill, it is an enormous centipede stifling independence. These sentiments resonated with Fondane, who was already in pursuit of a new conception of freedom.