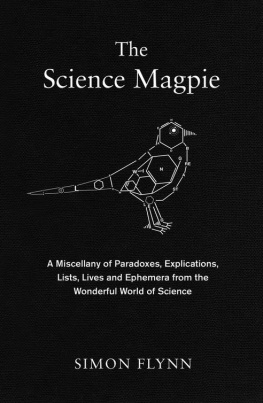

science, n.

5.b. Science. In modern use, often treated as synonymous with Natural and Physical Science, and thus restricted to those branches of study that relate to the phenomena of the material universe and their laws

magpie, n. and adj.

B. adj. (attrib.)

1. Magpie-like: with allusion to the birds traditional reputation for acquisitiveness, curiosity, etc.; indiscriminate, eclectic, varied.

Oxford English Dictionary

Science. What does that word conjure up in your mind? Writing over two hundred years ago, the great German authors Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gave this rather neat (if slightly silly-sounding) description in their collection of poetic epigrams, Xenien:

To one, its a high, heavenly goddess. To another its a cow that provides them with butter.

You might want to read that again. What they appear to be saying is that science can be viewed in terms of powerful ends (Im thinking of the very best metaphorical butter here) and almost spiritual, aesthetic means. In Schiller and Goethes eyes, at least, peoples responses tend to depend on which of these they focus on. But why not consider both? Why not acknowledge that one reason why science is so special is that both these aspects can be true?

There is more though. Science isnt just about laws, theories, formulae, processes and experiments. At heart its a human activity. Without the incredible individuals who have occupied themselves with uncovering the workings of nature and applying them to our benefit where would we be? Thats the last rhetorical question, I promise.

This miscellany is intended to showcase just some of the many and varied facets of science, plenty of which are unashamedly and idiosyncratically human. Its people who provide great stories and heart-warming anecdotes. Partly for this reason, the story of Erasto Mpemba, an African schoolboy who didnt give up in his quest to understand something (and who has a physical effect named after him as a result), and Darwins note on the pros and cons of marriage are among my favourite entries in these pages.

Although this book is a miscellany, certain themes and ideas echo through its pages. One of these is mathematics . You may have noticed the at the end of the definition of science given at the start of this introduction . Thats because I cheated slightly the definition actually continues sometimes with implied exclusion of pure mathematics. However, this magpie sides firmly with Roger Bacon, who said mathematics is the door and the key to the sciences and, as such, it is included. At least Im being honest.

A non-scientific realm that features rather heavily in the book is the arts, and poetry in particular. In contrast with science, artistic expression of any kind is typically felt to possess a power beyond the material. Im not sure quite how fair a view of science this is. But I believe that an appreciation of both realms of human endeavour can only be for the good, given the great wonders each offers. So, as writers are often told, show, dont tell. That has been the intention in those entries in the book where the two cultures overlap, such as The poets scientist and Siv Cederings Letter from Caroline Herschel.

And so to the final big theme in The Science Magpie. The splendid short story writer Katherine Mansfield once wrote, it is of immense importance to learn to laugh at ourselves and I couldnt agree more. From a smattering of groan-inducing jokes in some of the boxed fillers, to moments of more delicate wit from practitioners of science in entries such as Is Hell exothermic or endothermic? and A chemic union, sciences lighter side is very much on show because, as another writer, Colette, put it, an absence of humour renders life impossible.

Science has the power to enrich peoples lives, both figuratively and practically. What follows is a celebration of it, warts and all. I hope you enjoy it.

Simon Flynn, 2012

P.S.

In case it has been a while since you last did, or read, any science, Ive put together a brief back-to-school appendix (see page 256), which will hopefully remind you of some of the science you were taught at school and which may be useful to recall when reading this book. Dont worry, there wont be any exam at the end of it.

It seems only fitting to open The Science Magpie with a Hymn to Science, which first appeared in The Gentlemans Magazine in 1739 when its author, Mark Akenside, was only seventeen. The son of a butcher, it was around this time Akenside switched from preparing for a life as a nonconformist clergyman to training in medicine. He soon became a member of the Medical Society, eventually securing the position of physician to the Queen a little over twenty years later. Akenside wrote poetry throughout his life, including continuously revising his most famous work, The Pleasures of the Imagination, which Dr Johnson described as an example of the great felicity of genius.

From the Hymn to Science

Science! thou fair effusive ray

From the great source of mental Day,

Free, generous, and refind!

Descend with all thy treasures fraught,

Illumine each bewilderd thought,

And bless my labring mind.

But first with thy resistless light,

Disperse those phantoms from my sight,

Those mimic shades of thee:

The scholiasts learning, sophists cant,

The visionary bigots rant,

The monks philosophy.

O! let thy powerful charms impart

The patient head, the candid heart,

Devoted to thy sway;

Which no weak passions eer mislead,

Which still with dauntless steps proceed

Where Reason points the way.

Give me to learn such secret cause;

Let numbers, figures, motions laws

Reveald before me stand;

These to great Natures scenes apply,

And round the globe, and thro the sky,

Disclose her working hand.

Next, to thy nobler search resignd,

The busy, restless, human mind

Thro every maze pursue;

Detect Perception where it lies,

Catch the Ideas as they rise,

And all their changes view.

Say from what simple springs began

The vast ambitious thoughts of man,

Which range beyond controul,

Which seek Eternity to trace,

Dive thro th infinity of space,

And strain to grasp The Whole.

[]

There is no science without fancy and no art without facts.

Vladimir Nabokov (18991977)

Astronomers do IT in the dark.

Mathematicians do IT in numbers.

Biologists do IT in the field.

Chemists do IT periodically on the table.

Geologists do IT in folded beds.

Palaeontologists do IT in the dirt.

Computer scientists do IT bit by bit.

Electrical engineers do IT until it hertz.

Physicists do IT with force.

When seismologists do IT, the Earth shakes.

Zoologists do IT with animals.

Quantum physicists do IT uncertainly.

Polymer chemists do IT in chains.

Cosmologists do IT with a bang.

Theorists do IT on paper.

Geneticists do IT in their genes.

Statisticians do IT with 99% confidence.