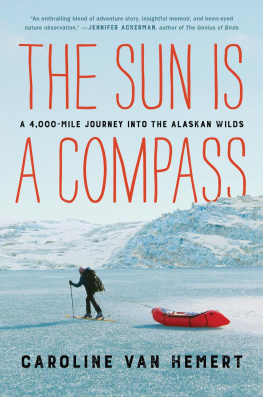

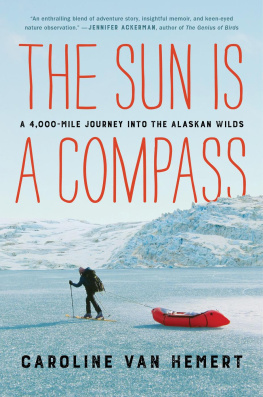

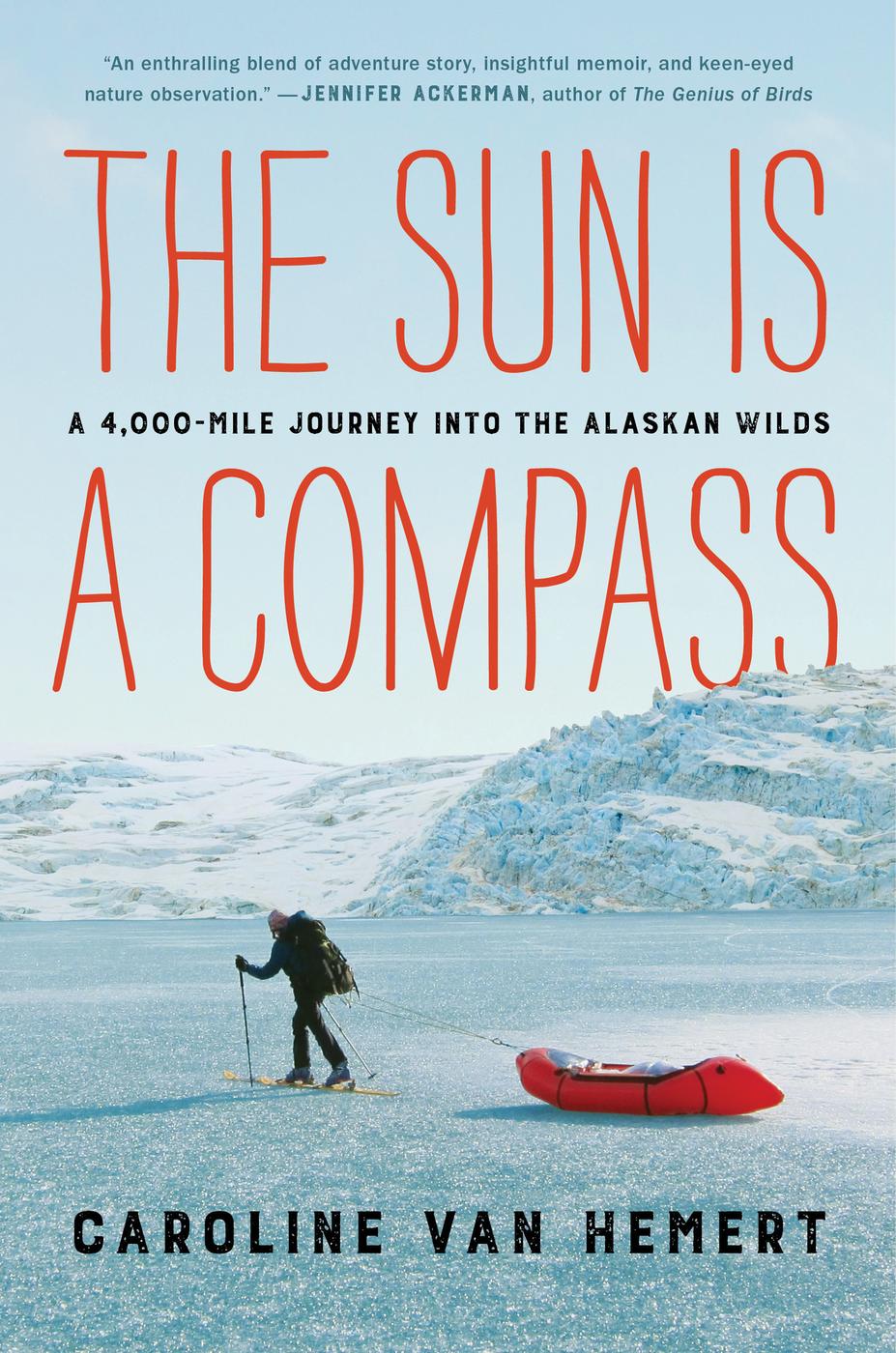

Copyright 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert

Cover design by Lucy Kim

Cover and author photograph courtesy of the author

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown Spark

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrownspark.com

twitter.com/lbsparkbooks

facebook.com/littlebrownspark

First ebook edition: March 2019

Little, Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Photographs by Caroline Van Hemert and Patrick Farrell

Illustrations by Patrick Farrell

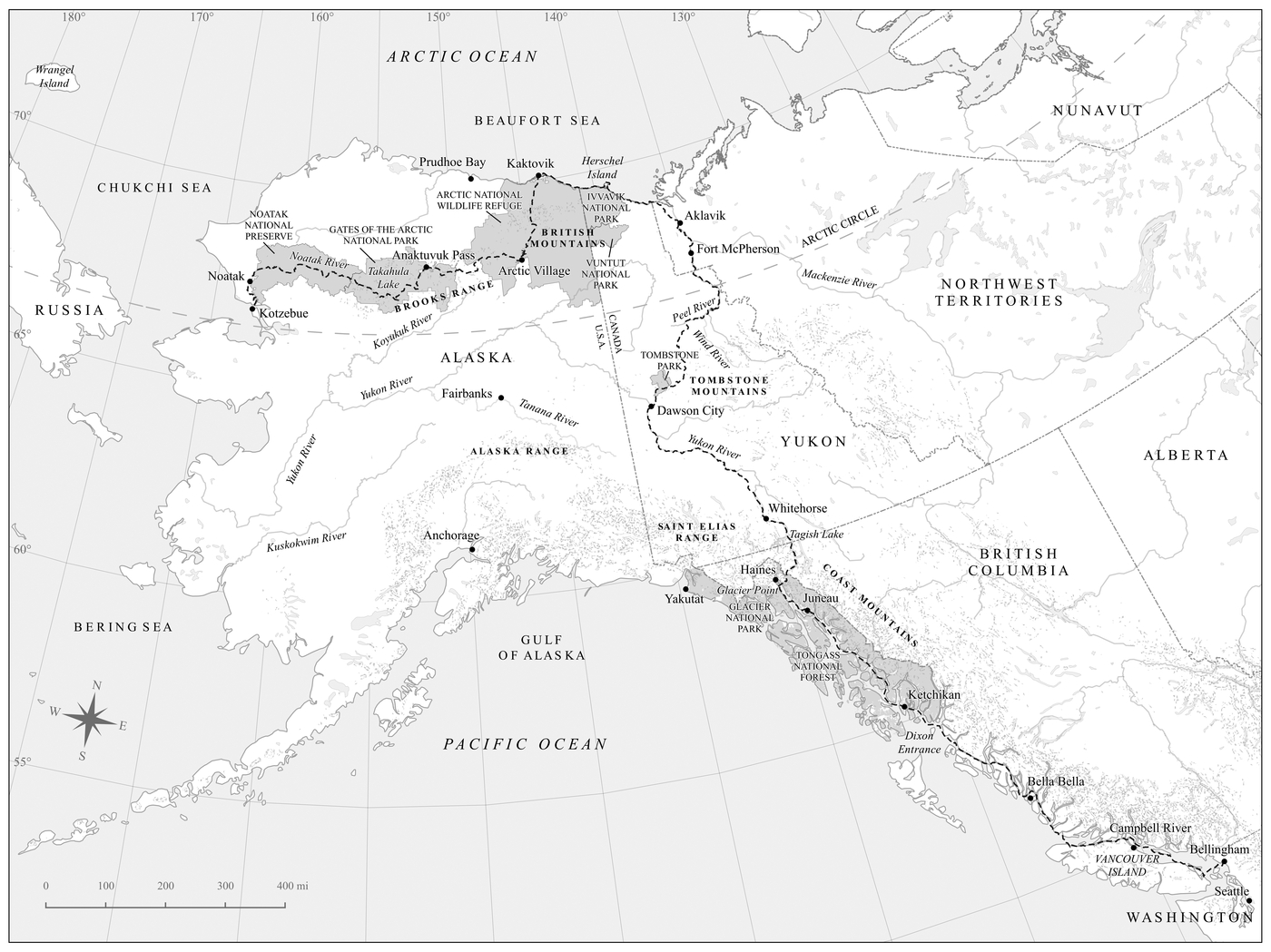

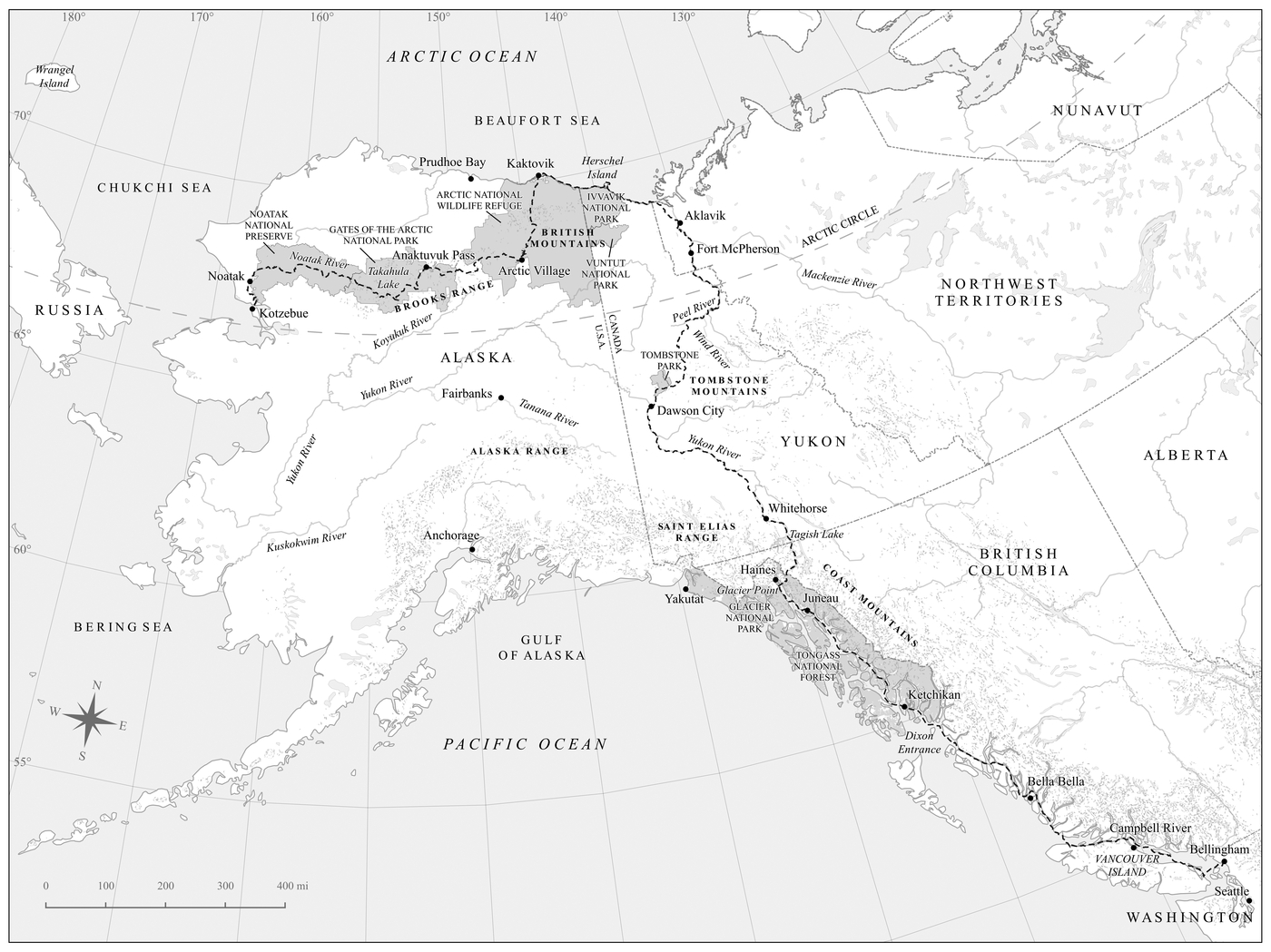

Map by Colin Shanley

ISBN 978-0-316-41443-2

E3-20190103-DA

For Pat, my partner in everything

Prologue

Swimming the Chandalar

I m standing on the bank of the swift Chandalar River in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska, trying to gather the courage to swim across. My husband, Pat, is by my side. Were alone, as we have been for most of the past five months.

The sky is a depthless sort of overcast, no definition in the clouds, no glimmer of sunshine. The temperature hovers just above freezing and the air is damp after a night of rain. I grip the straps of my pack, my fingers raw from the chill, and lean against Pat as we look down at the river that flows in a wide channel sixty feet below us. The only sound is the steady rush of moving water. I push away the voice in my head that echoes a single question. What are we doing?

Its the fifth of August, 2012. Over the last 139 days, we have traversed nearly three thousand miles, most recently through places so lightly traveled our topographic maps have little to say about them. Only the highest peaks are labeled, and then solely by elevation. The Brooks Range is the northernmost major mountain range on earth and has retained its integrity in ways that few places have. Many of the creeks and valleys are nameless, their curves and riffles left unexplored. There are no soft edges here, no boardwalks or trails or park rangers. Its wild, empty, and gritty.

Were here because were attempting to travel entirely under our own power from the Pacific Northwest to a remote corner of the Alaskan Arctic. Were here because we need wilderness like we need water or air. Like we need each other. For me, this trip is also a journey back to trees and birdsong, to lichen and hoof prints. Before leaving, I had lost my way on the path that carried me from biology to natural wonder. I had forgotten what it meant, not only in my mind, but in my heart, to be a scientist.

We have a thousand miles ahead of us, but for now all that matters is this river. On the map it looked harmless, squiggly and blue. As I stare down at it now, its the color of mud. From our elevated vantage, the waters opaque surface appears smooth, but when Pat throws a spruce bough from the bank, it bobs in the small waves, spins once, then vanishes quickly downriver.

In the first months of the journey, our destination was so distant that it seemed almost peripheral. Kotzebue. A small village on the shores of the Chukchi Sea. A place on the map as arbitrary as any other. We were consumed by each day, distracted by aching muscles and whales and the simple act of moving. Always moving. But the stakes quietly grew, shape-shifting from a tally of miles into something much more. Only now am I beginning to see this trip for what it is. A celebration and a letting go of youth. A reawakening of the biologist in me. A reckoning between us and the land. Something we must see through to the end.

And so crossing this river has become necessary, in the way that its necessary to kiss a lover before leaving, to pause and look up when the moon is rising. Our bodies know what is essential and what is not.

Before we left, people asked us why we were taking this trip; they wondered what compelled us to want to disappear for a while. I tried to explain that escapism wasnt our goalneither of us was running from a broken marriage or drug addiction or academic failure. We werent trying to set a record or achieve a first. We were simply trying to find our way home.

Shortly after Pat and I met in 2001, we discovered that we were most fully ourselves in wild places. That our love was strongest among rocks and rivers, trees and tundra. Since our first summer together, when we spent two months camped on the bank of a remote Arctic river, we had dreamed about another grand adventure. Increasingly, though, time in the outdoors was taking a backseat to more mundane endeavors. Our trips were shrinking, our commitments growing. Even worse, I had just finished a Ph.D. in biology feeling more distant than ever from the natural world. Five years of study had started as an act of love and turned into pure drudgery.

My research focused on a strange cluster of beak deformities that had recently emerged among Alaskan chickadees and other birds. The afflicted birds grew curled and grotesque beaks that resembled something from a dark version of Dr. Seuss. When I began my graduate project, I was sure I could find answers to the mystery of the beak deformities, and that the resulting facts would matter. I fancied myself something of a wildlife detective, searching for clues that would help me crack the case. But instead I quickly learned that the most basic information about the anatomy of a birds beak was not yet available, and I had no choice but to ask the simplest questions first. I began with the tedious, unglamorous work of slicing beaks into impossibly thin pieces using miniature knives and examining them under high-powered microscopes. I housed chickadees in a laboratory and studied the way their beaks grew, feeling remorse each time I stepped into the room and stared at two dozen pairs of eyes that would never again see birch leaves fluttering in the wind or probe a trees bark for spiders and beetles.

The tiny black-capped chickadees whose familiar calls belie the fact that they are actually one of the most remarkable species on earth were first my inspiration and then, later, my bane. When my advisor toasted me after my dissertation defense, I cringed, knowing I had failed in the most fundamental of ways. This wasnt a failure in the traditional sensemy calculations stood up to scrutiny, my experiments worked, my chapters were well written. But underneath it all was the ugly fact that I simply didnt care anymore. Between hundreds of hours peering under a microscope and observing chickadees in cages, I had forgotten why Id wanted to be a biologist in the first place.