This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For my aunt Ike and my brother Fred

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011

http://www.archive.org/details/shambhalaguidetoOOreid

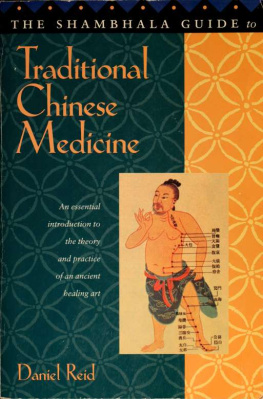

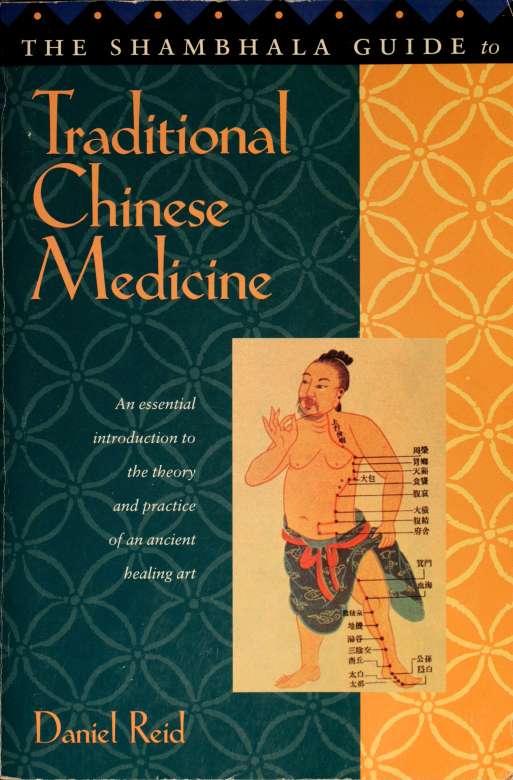

The Shambhala Guide to Traditional Chinese Medicine

Introduction

In traditional Chinese medicine, the human system is viewed as a microcosmic mirror of the macrocosmic universe, a whole inner world composed of the same elements and energies, and subject to the same natural laws, as the external world and cosmos (fig. 1). The universal principles that govern "everything under Heaven" (tien hsia) are simply known as the "Way" (Tao), and they apply equally to stars and planets, molecules and atoms, operating exactly the same way in the human system as they do in the solar system. Because nature is the most obvious and enduring manifestation of Tao on earth, much of the traditional terminology of Chinese medicine is derived directly from natural phenomena (fire and water, wind and heat, dryness and dampness, etc.), and a traditional Chinese diagnosis often sounds more like a weather report than a medical analysis. In Chinese medicine, manifest nature is the master template by which the physician understands and manipulates the internal elements and energies of the human system.

When the elemental energies within the human system remain in a natural state of dynamic balance and functional harmony, "fair weather" prevails inside the body, and the garden of human health flourishes, both mentally and physically. But when organic balance

Introduction

Figure 1. An ancient Chinese depiction of the human system as a microcosm of nature and the cosmos.

Introduction 3

is upset and aberrant energies invade the system, flood and drought, wind and rain, heat and cold, and other types of "stormy weather" may occur, causing damage to the internal landscape. Because the microcosmic energy system of humans (yen) stands midway between the cosmic powers of Heaven (tien) and the natural forces of Earth (di), drawing power from both sources, human health depends not only on internal energy balance within the system, but also on harmony with the macrocosmic powers of Heaven (the cosmos) and Earth (nature).

Two key concepts in traditional Chinese medicine are that the occurrence of disease represents a failure in preventive health care, and that health is a responsibility shared equally by doctor and patient. In the Chinese medical tradition, the doctor serves mainly as advisor and guide, the coach who teaches the patient the basic ground rules and winning strategies in the game of health, but it is up to each individual to play the game and win or lose the prize of health. The key tactic in the game of health is timing and preventive intervention. As the classic verse of the Tao Teh Ching states,

Before an omen arises, It's easy to take preventive measures... Deal with things in their formative state; Put things in order before they grow confused.

The traditional Chinese approach to health is summarized in the old English adage, "A stitch in time saves nine." The Chinese have always realized the wisdom of spending time and money on a preventive stitch now, rather than having to pay the pain and cost of nine curative stitches later. That is one reason that Chinese in all walks of life rarely stint on expenditures for food: they learned long ago that you are what you eat, and they know that wholesome food is always the best preventive medicine. In the Western world today, people tend to take health for granted until it breaks down, then run

to the doctor looking for a quick fix or a spare part. "Such an approach," states The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine, "is comparable to the behavior of a person who starts digging a well only after he is thirsty, or who begins to forge weapons after he is already engaged in battle. Would these actions not be too late?"

"The superior physician," says an old Chinese medical axiom, "teaches his patients how to stay healthy." In traditional Chinese households, the family doctor was retained not just to treat the sick but to keep everyone in the family, including the servants, healthy. The physician visited the household regularly, checking everyone's pulse and other vital signs and dispensing timely advice and remedies as required in order to deal with things in their formative state. As long as everyone in the household remained healthy, the doctor received a regular monthly fee, but if anyone fell ill, all payments stopped until the doctor restored the patient to health, at the doctor's own expense! Not only was this system an excellent preventive against disease, it was also a very effective preventive against malpractice and a strong incentive to creative progress in health care, for the income of physicians depended entirely on keeping their clients healthy, not on treating them for diseases that could easily have been prevented with "a stitch in time," as is all too often the case in modern Western medicine.

Traditional Chinese doctors diagnose and treat the whole human system, rather than dealing only with its separate parts, as the specialists of modern Western medicine do. Western medicine tends to focus on the overt symptoms of disease in the part of the body where they occur, treating each condition in the same way in every patient, as though the symptom were an independent phenomenon unrelated to other parts of the body and the external environment. The Chinese describe this sort of medical care as suppressing the superficial symptoms while failing to cure the root cause. By contrast, Chinese medicine diagnoses and treats all symptoms of disease in terms of their functional relationships to the whole human system,

as well as to external factors in the environment in which the symptoms developed. Primary attention is always focused on the subtle governing energies that operate decisively below the surface, not on the obvious external symptoms they create outside. This is called "curing the root, not treating the surface."

The Chinese view the human body as an organic system whose parts are all functionally interrelated by virtue of the same fundamental forces that govern nature and the cosmos, of which the human system is a microcosmic but complete reflection. As Ted Kaptchuk explains in The Web That Has No Weaver,

To Western medicine, understanding an illness means uncovering a distinct entity that is separate from the patient's being; to Chinese medicine, understanding means perceiving the relationships between all the patient's signs and symptoms.... The Chinese method is thus holistic, based on the idea that no single part can be understood except in its relation to the whole.... If a person has a symptom, Chinese medicine wants to know how the svmptom fits into the patient's entire bodily pattern.... Understanding that overall pattern, with the symptom as part of it, is the challenge of Chinese medicine.