Better Than Carrots or Sticks: Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management

Dominique Smith, Douglas B. Fisher, and Nancy E. Frey

Table of Contents

Publisher's note: This e-book has been formatted for viewing on e-reading devices. If you find some figures hard to read on your device, try viewing through the Kindle for PC (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/pc) or Kindle for Mac (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/mac) applications on your laptop or desktop computer.

ASCD 2015

Chapter 1

Punitive or Restorative: The Choice Is Yours

....................

A colleague of ours once projected the following quote, widely attributed to Frederick Douglass, onto a screen at the start of a professional development session:

It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.She then asked the assembled faculty to write down their own reactions to the statement and discuss them in small groups. The reactions our colleague heard were both positive and predictable: a lot of talk about the influence of students' family, school climate, and a sense of connectedness within the school on academic achievement.

When the conversations drew to a close, our colleague shared the school's discipline data from the previous year, which showed that suspensions occurred at rates disproportionate to the student population. In a majority of cases, the most serious offense was identified as defiancea nonviolent act, and one that is broad and vaguely defined. This is not an uncommon finding: According to a report of suspensions in California schools, 34 percent of suspended students were punished for defiance or disruption (Losen, Martinez, & Okelola, 2014). Our administrator friend had calculated the number of instructional days lost to suspensions and provided comparative data on the grade point averages of suspended students versus those who had never been suspended. She then asked the faculty whether they were building strong children or ensuring that their communities will have future broken adults in need of repair. The frank 30-minute discussion that ensued inspired the school's staff to create a culture in which restorative practices could thrive. Over countless department meetings and informal exchanges, the staff performed yeomen's work analyzing and redefining classroom and schoolwide practices.

Our own experience has been that while our collective hearts as educators are in the right place, we tend to make decisions based on past experience. After all, we began our on-the-job training as teachers when we were five years old. Our beliefs about school, classroom management, and discipline have been shaped by decades of experience, starting in kindergarten. What we need is an effective classroom-management systemone that we can hold onto in times of stress and strife.

Effective Classroom Management

The term classroom management is confusing and misleading, mainly because it has no clear and widely agreed-upon definition. For some, the term refers to general control of students; for others, it refers to discipline procedures; for others still, it refers to both routines and procedures. Up until recently, we have avoided using the term, but we finally came across a definition we could stand behind: Cassetta and Sawyer (2013) define classroom management as being "about building relationships with students and teaching social skills along with academic skills" (p. 16), and we couldn't agree more.

There are two aspects of an effective learning environment (and, by extension, successful classroom management): relationships (specifically, the range of interpersonal skills necessary to maintain healthy relationships) and high-quality instruction. When students have strong, trusting relationships both with the adults in the school and with their peers, and when their lessons are interesting and relevant, it's harder for them to misbehave.

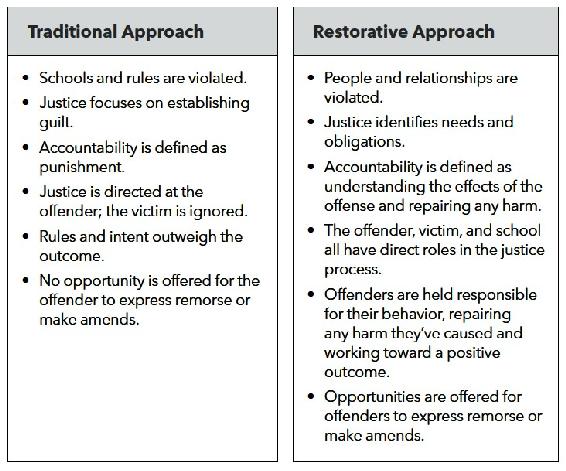

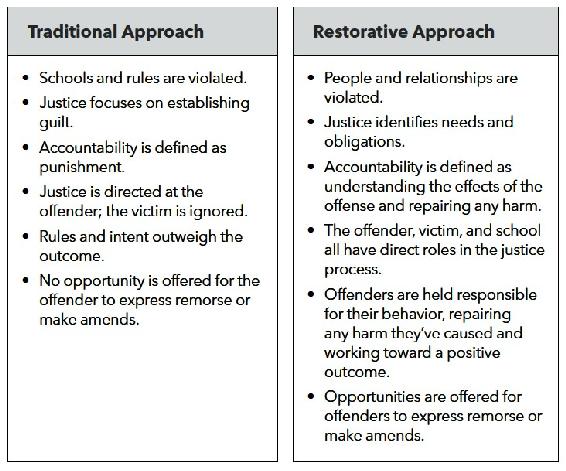

We don't expect an effective classroom-management system to eliminate all problematic behavior any more than we expect a new set of standards to raise all students' scores by leaps and bounds on the first try. Students are going to misbehave as they learn and growit's how we respond to their misbehavior that matters. We believe that students should have a chance to learn from their mistakes and to restore any damaged relationships with others. Our view is known as the restorative approach to discipline. The table in Figure 1.1, developed by the San Francisco Unified School District, illustrates the differences between the restorative approach and the traditional approach to discipline.

Figure 1.1 Traditional Versus Restorative Approach to Discipline

Source: Adapted from San Francisco Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative practices whole-school implementation guide (p. 19). San Francisco, CA: Author.

The Restorative Practices Movement in Schools

In its contemporary incarnation, the restorative practices movement is an offshoot of the restorative justice model used by courts and law-enforcement agencies around the world. In the restorative justice model, mutually consenting victims and offenders meet so that the former can be given a voice and the latter can have an opportunity to make amends. Importantly, this approach empowers a community to take an active role in resolving problems. Cultures throughout the world employ restorative justice to create peace among adversaries, ensure restitution, and make decisions at times of community crisis.

Restorative practices in schools cast a wider net than restorative justice in the courts. Whereas justice is by its nature reactive, restorative practices also include preventive measures designed to build skills and capacity in students as well as adults.

Restorative practices are predicated on the positive relationships that students and adults have with one another. Simply said, it's harder for students to act defiantly or disrespectfully toward adults who clearly care about them and their future. Healthy and productive relationships between and among students and staff facilitate a positive school climate and learning environment. In the restorative approach, when relationships in the school become damaged, the parties involved are encouraged to engage in reflective conversations that help offenders understand the harm that their actions caused and provide them with opportunities to make amends. As we describe further in this book, there are a number of ways to build relationships and create healthy learning communities.

Circles. Teachers in the restorative practices movement promote a sense of family in the classroom by having students sit in circles to discuss both curriculum-related topics (e.g., the role of genocide and war in a World History class) and noncurricular issues that bear discussing (e.g., how students might manage stress on the eve of a major state exam).

Individual conferences to address problematic behavior. We'll explore the details of these high-stakes meetings in greater detail further in the book, but for now know that restorative practices are not about letting things go or ignoring when harm has been done. Individual conferences require intense preparation on the part of the victim(s), the perpetrator(s), witnesses to the conflict, and anyone else who's been affected by it. In some cases, conferences involve two sets of parents or guardians who are very much at odds with each other: it's common for the offender's family to lobby for mercy and for the victim's family to demand retribution. To ensure that conferences run smoothly, it is crucial to engage with families preventively, before crises occur.

Source: Adapted from San Francisco Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative practices whole-school implementation guide (p. 19). San Francisco, CA: Author.

Source: Adapted from San Francisco Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative practices whole-school implementation guide (p. 19). San Francisco, CA: Author.