Totalitarian Space and the

Destruction of Aura

Totalitarian Space and the

Destruction of Aura

Saladdin Ahmed

Cover image: Arrow Into Infinity by Milad Safabakhsh

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ahmed, Saladdin, 1972 author.

Title: Totalitarian space and the destruction of aura / Saladdin Ahmed.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014128 | ISBN 9781438472911 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438472935 (ebook)

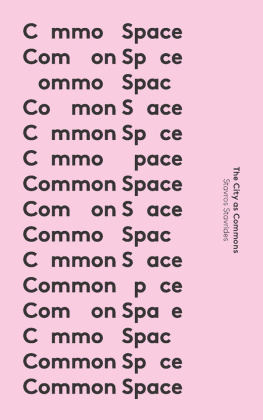

Subjects: LCSH: SpacePhilosophy. | SpacePolitical aspects. | TotalitarianismSocial aspects. | Critical theory.

Classification: LCC BH301.S65 A56 2019 | DDC 114dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014128

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the hopeless ones

whose struggle is our only hope .

Contents

Acknowledgments

First, the utmost thanks to Melissa Seelye, who alone knows how much she helped me in everything.

Next, I would like to thank the anonymous readers whose faith in the project and insightful comments on the manuscript encouraged me to make significant changes, especially to the first and last chapters. To Michael Rinella, senior acquisitions editor at SUNY Press, whose professionalism, punctuality, and interest in the project has been unwavering, I extend my sincerest thanks. I also appreciate the work of SUNYs senior production editor, Diane Ganeles; senior promotion manager, Michael Campochiaro; copy editor Laura Tendler; and the other members of the production and marketing teams who saw this book through to completion.

Further thanks, of course, are also due to Douglas Moggach, who was my PhD supervisor at the University of Ottawa. His support was instrumental to my completion of the dissertation, and I am especially grateful for his suggestion to integrate a discussion of Rousseau and Herder. The feedback from the members of my PhD committee, Denis Dumas, Isabelle Thomas-Fogiel, Viren Murthy, and Justin Paulson, as well as my external reader, Samir Gandesha, was also invaluable. Justin was extremely generous with his time and comments, despite the short notice, and Samirs flexibility ensured that the show could go on.

For the indexing, I send many thanks to my friend Vasile-Valentin Latiu, who, as always, undertook the task without a moments hesitation. I am also thankful to Arezoo Islami, Duncan Rayside, Shahrzad Mojab, Hassan Ghazi, Eric Davis, Andrew Scerri, and Blair Taylor for their interest in the manuscript and encouragement. As well, the help of Sarina Simon Rosenthal, Rose Anderson, and Lauren E. Crain of Scholars at Risk over the last few years has meant a great deal to me. Here I must also acknowledge friends near and far who have supported me over the years, especially Siyaves Azeri, Ibrahim Bor, Jol Doucet, Alice Constantinou, Eleanor Finley, Amir Hassanpour (whose fight will live on), Greg Younger-Lewis, Anna Markova, Abolfazl Masoumi, Hodan Mohamed, Madalina Santos, Jaffer Sheyholislami, Kamal Soleimani, and Noel Ward.

Parts of the third chapter were published in an article titled Panopticism and Totalitarian Space in the Theory in Action journal. Thanks to the editor-in-chief, John Asimakopoulos, for kindly granting me permission to republish those here.

Introduction

Recall, for a moment, the wonder with which you once observed the movements of worker ants. Whether visibly united to move a large object or building an anthill one grain of sand at a time, the ant colony at work is an endless source of fascination. To us on the outside, their regimented movements and often frenetic pace seem strange, comical even, but what would we discover if we turned this outsiders gaze on ourselves? Imagine how our urban spaces would be perceived by someone entirely unfamiliar with our dominant socioeconomic norms. At sunrise, the outsider would likely note the systematic division and subdivision of cities by innumerable highways, forming orderly geometric shapes and patterns. She would see the blocks of concrete and glass jutting into the sky, separated, connected, and framed by the grid of city streets. At the appointed hour, these highways and streets would be overtaken by a seemingly endless procession of cars and buses, and she would watch in astonishment as the lines of machines inch their way along. Zooming in closer, the observer would quickly realize that the city is a space of and for machines that orchestrate the mass movement of humans and commodities between points of production and consumption. To her, we would no doubt look like the most domesticated of all creatures, with our movements incomparably more prescribed than the worker ants we gaze down on.

Perceived in its totality, this scene can give us insight into the truth of our spatial lives that we could never otherwise imagine. It would be inaccurate to say that the millions of people who are on the move en masse at certain times of the day are physically coerced in the way that people are forced to work in labor camps. Still, there must be a force behind these highly organized patterns of movement and spatial organization. Behind every hegemonic order, there is a system responsible for its creation and reproduction; nothing in our produced environment is natural. In our case, that hegemonic order is capitalism, and it dictates the organization of human activities as well as the ways in which objects are transformed through those activities and the simultaneous transformation of humans within that process. Indeed, the hegemony of capitalism is such that we have not yet been able to comprehend the scope of our unfreedom, the degree to which our lives are mechanized by the power of capital.

Our obsession with time and history has made us neglect the very pressing question of how the capitalist distribution of space affects our everyday lived experience. The dominant mode of spatiality is fundamentally transparent, which is indicative of our non-freedom. We live in a unified space that is chillingly flat, mechanized, and open to the policing gaze of power. And yet we go along with it. We tacitly accept being watched by unknown individuals whom we view as disembodied elements of the institution of the state and its corporate associates. In fact, we do this despite the commonsensical fact that working in the service of the state does not make anyone more ethical, and it certainly should not make anyone more entitled to penetrate other peoples lives. Some of us may comfort ourselves with the belief that we have nothing to hide, and that the surveillance is therefore benign. In doing so, we essentially submit to punishment for a crime that we have not committed. To prove her innocence, the citizen must consent to being naked before the gaze of power, conducting herself in such a way that she would never do anything that could not be made public.