|

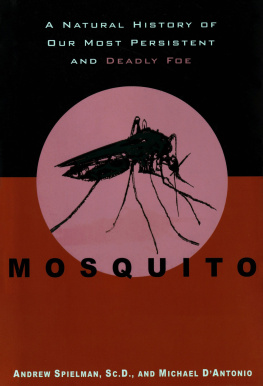

MOSQUITO A Natural History of Our

Most Persistent and Deadly Foe |

Andrew Spielman, Sc.D.

and Michael DAntonio

Hyperion

New York

2001 Andrew Spielman, Sc.D. and Michael DAntonio

Photographs by Leonard E. Munstermann, Yale School of Medicine and Yale Peabody Museum. Maps by Paul J. Pugliese

Hyperion, 77 W 66th Street, New York. New York 10023-6298.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spielman, A. (Andrew)

Mosquito : A natural history of our most persistent and deadly foe / by Andrew Spielman and Michael DAntonio.1st ed.

ISBN 0-7868-6781-7

I. Mosquitoes. 2. Mosquitoes as carriers of disease. I. DAntonio. Michael.

II. Title.

Book design by Casey Hampton.

FOR JUDITH AND TONI,

our true collaborators

NOTE TO THE READER

This book is a collaboration between a journalist, Michael DAntonio, and a scientist, me. The stories and anecdotes told in first-person singular recount experiences from my career and my travels around the world. I hope these stories, and this book in its entirety, will lead you to respect and, perhaps, admire the mosquito as something more than just a pest or a vector of disease. Few creatures on earth are more worthy of scientific inquiry and human wonder.

Andrew Spielman

Contents

Acknowledgement

All authors depend on those who came before. Mosquito stands on a tradition of tropical medicine and entomology that is more than a century old, and we have drawn on it here. We are also grateful to have had access to the papers, documents, and volumes of both the Harvard School of Public Health and the universitys Countway Library.

Many people provided us with valuable encouragement and advice. However we are most indebted to Deb Rebelo for her research assistance and to Richard Pollack, Ph.D., for both scientific and literary advice. Odessa Deffenbaugh was instrumental in getting our final manuscript in shape. And our editor, Will Schwalbe, gave us invaluable support and assistance.

If you would see all of Nature gathered up at one point, in all her loveliness, and her skill, and her deadliness, and her sex, where would you find a more exquisite symbol than the Mosquito?

Havelock Ellis , 1920

Preface:

The Trouble with Mosquitoes |

|

It is the kind of everyday event that in the wrong place and time becomes unnerving. You are on vacation. Perhaps you are strolling at dusk along Fifth Avenue in New York. Maybe youve been taking pictures in the bush in Kenya, or you are stepping off a ferry in Hong Kong. In a quiet moment you feel the itch behind your knee. You reach down and touch a hot, raised welta mosquito biteand you wonder:

Do mosquitoes in this place carry disease?

Is an outbreak under way?

What are the odds that the particular mosquito that drained my blood left something deadly behind?

The mere fact that we ask these questions demonstrates the power of the mosquito. No animal on earth has touched so directly and profoundly the lives of so many human beings. For all of history and all over the globe she has been a nuisance, a pain, and an angel of death. Mosquitoes have felled great leaders, decimated armies, and decided the fates of nations. All this, and she is roughly the size and weight of a grape seed.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the mosquito and the pathogens she transmits command attention worldwide. Each year millions die from mosquito-borne malaria. National economies are locked in isolation as a result, in part, of the same disease. Cities in Europe and the United States battle outbreaks of West Nile virus. Dozens of countries fight yellow fever, dengue, filariasis, and a host of deadly encephalitis viruses.

To meet the health threats that are growing worse in many corners of the world, we must know the mosquito and see clearly her place in nature. More important, we should understand many aspects of our relationship to this tiny, ubiquitous insect, and appreciate our long, historical struggle to share this planet.

When I was a college student in the early 1950s, nothing held more drama than the fight to save the world from the diseases that these creatures carried. The entomologists, parasitologists, and physicians in this corner of science conducted fascinating experiments in the lab. Some traveled to exotic, even dangerous places in brave crusades to save lives. They hacked through jungles, paddled up croc-infested streams, braved contact with hostile peoples, all in service to humanity.

I was not the only undergrad at Colorado College to have this interest. An older student who lived across the hallway in my dorm shared my delight with this field. Every day, Phil Longenecker seemed to announce something fascinating and a little grotesque that he had read somewhere or other. A classic example: the way mosquitoes serve botflies in Central and South America. The size of a bumblebee, the fly seizes a mosquito in midair and glues her own eggs to her captives abdomen. Later, when the mosquito feeds on a person, the damp warmth of human skin causes the flys eggs to hatch, leaving maggots to burrow into the new host. Soon, the maggots breathing apparatus can be seen poking through the victims skin. Within a week, its as large as a small olive.

In 1951, I accompanied one of my professors on a train trip to Chicago to attend the organizational meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, an annual event that brings together specialists in tropical medicine from all over the world. The conference would mark the moment when a young man who grew up fascinated by the natural world became dedicated to entomology and public health.

I listened for five days as intensely bright and confident men gave talks on parasites and on mosquitoes in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. A keynote speaker described the valiant effort that defeated yellow fever so that the Panama Canal might be built. Stooped and aged, Joseph LePrince, sanitary engineer, seemed to me as though he were a thousand years old. But though his voice creaked, his tale was spellbinding, filled with heroism in the face of great danger. Before the mosquito fighters prevailed, earthmovers were silenced as armies of men languished in hospitals, and coffins lined the platforms at railway stations.

The mosquito men I met at that meetingat the time they were all menseemed intelligent and incredibly daring. I wanted to be one of them. Advanced study at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health and a tour of duty in the United States Navy led to a professorship at Harvard. In my time I have felt both the thrill of discovery and felt the pangs of failure. But after fifty years, the work continues to bring endless challenges and surprises.

The truth of a career in entomology and tropical public health turned out to be as exciting, to me, as its anticipation. Though I could never approach the heights scaled by such pioneers as Patrick Manson, Ronald Ross, and Walter Reed, I shared in their adventure during a time when everything in science seemed possible.

It may be difficult to love the mosquito, but anyone who comes to know her well develops a deep appreciation. A few species, like the iridescent blue-lined Uranotaenia sapphirina, are truly beautiful. All manifest exquisite adaptation to their environment. As a larva, the mosquito feeds and navigates in water. As an adult, she walks on water as well as land. She flies through the night air with the aid of the stars. She not only sees and smells but also senses heat from a distance. Lacking our kind of a brain, she nevertheless thinks with her skin, changing direction, and fleeing danger in response to myriad changes in her surroundings.

Next page