Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Operation Bite Back: Rod Coronados War to Save American Wilderness

Burning Rainbow Farm: How a Stoner Utopia Went Up in Smoke

To Nancy, Joe, Brett and Ayron, and especially to Bruce, who dug in

I can only seek you if I take the sand into my mouth

So I can taste resurrection

Nelly Sachs

Contents

A relative who once stayed with us at the cabin complained: Did you hear all those people talking in the woods last night? Our cabin sits among vast federal swamps in a depopulated corner of Michigan, with farms on either side, and other than a few barking dogs we dont hear much of the neighbors. Pretty much never. When that was pointed out to her, her eyes got wider and wider as she decided, if those werent live people murmuring in the trees, then they must be dead ones. Spirits, she said.

The talking out there is real enough. It wakes me up, too. A whitetail deer has been snorting outside the open window of my tiny cabin bedroom for half an hour CHUUU like a horse blowing or a person winded by hauling in a load of wood. Its the middle of a warm June night throbbing with cricket song and katydid shrill and bullfrog whomp; there are creatures moving.

But those arent the spirits she was talking about. I woke, like I have a hundred times here, to the impression of whispering at the window screen. In the gaps between snort and whomp theyre there, too low to grasp, exactly, but voices. The forest itself, I guess. I squeeze my eyes shut and focus, and when I do they seem to come from a particular direction, hard to nail down. They are softly urgent, wanting things. Like the presence of people standing stone-still in the woods.

Theres no sleeping through that. I get out of bed and put on water for tea by the weak glow of a nightlight, then slip by the dogs without letting them out the sliding door and sneak onto the porch to find out what all the murmuring is about.

My youngest brother, Joe, is already out on the porch taking notes. Im not surprised to find him out there, but it is four A.M. Hes been out there pretty much all night. The universe breathes a night wind and Joe is counting the breaths, scratching on a notepad while he sits with a hoodie tied around his face and a lit cigarette to keep away the mosquitoes. He gives me a big toothy smile but doesnt say anything, turning immediately back to the field of orchard grass that stretches away into the night. He doesnt want to miss anything.

Whats that deer huffing at? I say, low.

You, now, he says.

Joe only sleeps one night out of every four or so, a circadian scar: a constant reminder of troubles that started long before we got this deer camp a quarter century ago. Hes a big man, six foot one and running about 220, barrel-chested and banged up. One knee doesnt work and his back was broke once, and when hes not obsessively changing toilets in the apartments he owns, hes likely to be fly-fishing or sitting out here on the porch. He chews ice out of a big dirty Slurpee cup held together with duct tape. He has turned the fridge into an ice farm and superintends five trays of ice there in various states of ripeness and is constantly getting expensive dental work done.

He picks up a pair of field glasses, peers into the darkness, puts them back down.

I look at his notepad, where hes scribbled about barred owls in the south twenty. Coyote pack running through Mr. Carters, the farmer to the west. Kept a tally of deer on the corn feeder. Raccoon fight in the red pines. Sandhill cranes. A loon.

We write down what we hear talking in the fields at night like other people write down dreams. Because they mean something.

A huge stonefly makes for the hot cherry of Joes cigarette and bats him in the face and he snatches it; on his forearm he has a six-inch tattoo of a mayfly known to all fly fishermen as a Hendrickson, the Ephemerella subvaria . He studies the stonefly closely, then releases it into the darkness.

Our middle brother, Brett, emerges onto the porch with a cup of coffee and his longtime partner, Ayron, the sister we never had. She shuffles past in slippers and a jacket and says to me, low, You going out?

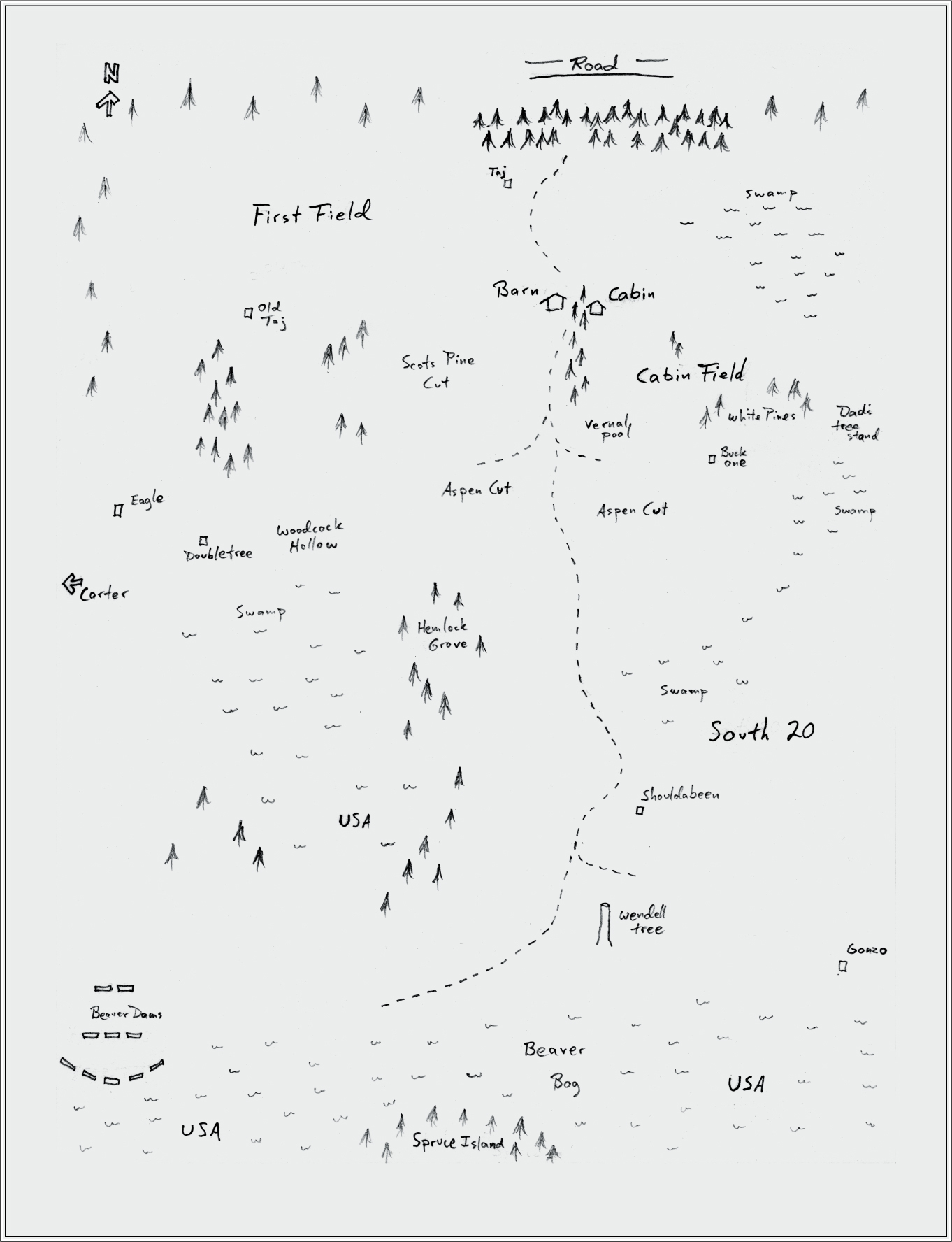

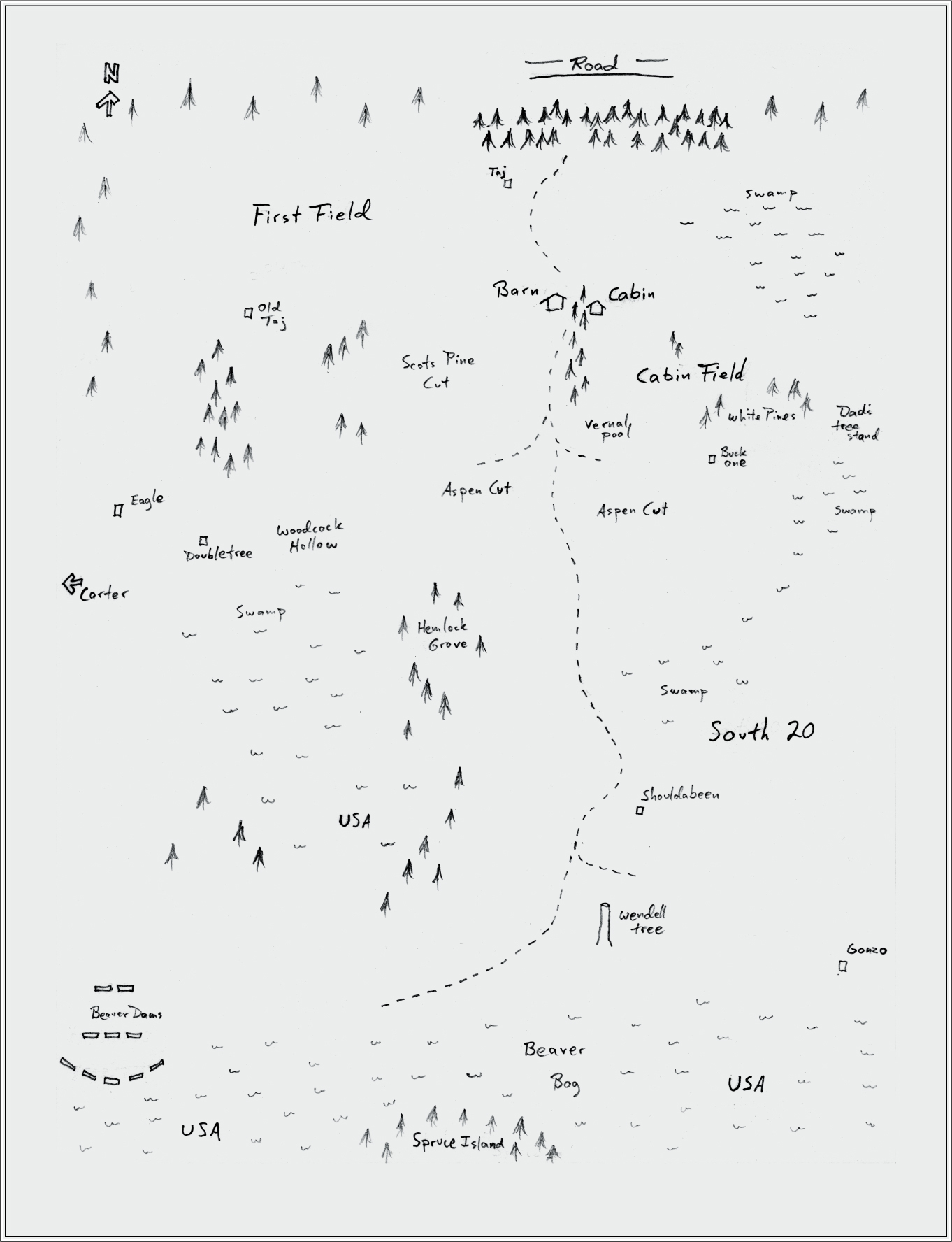

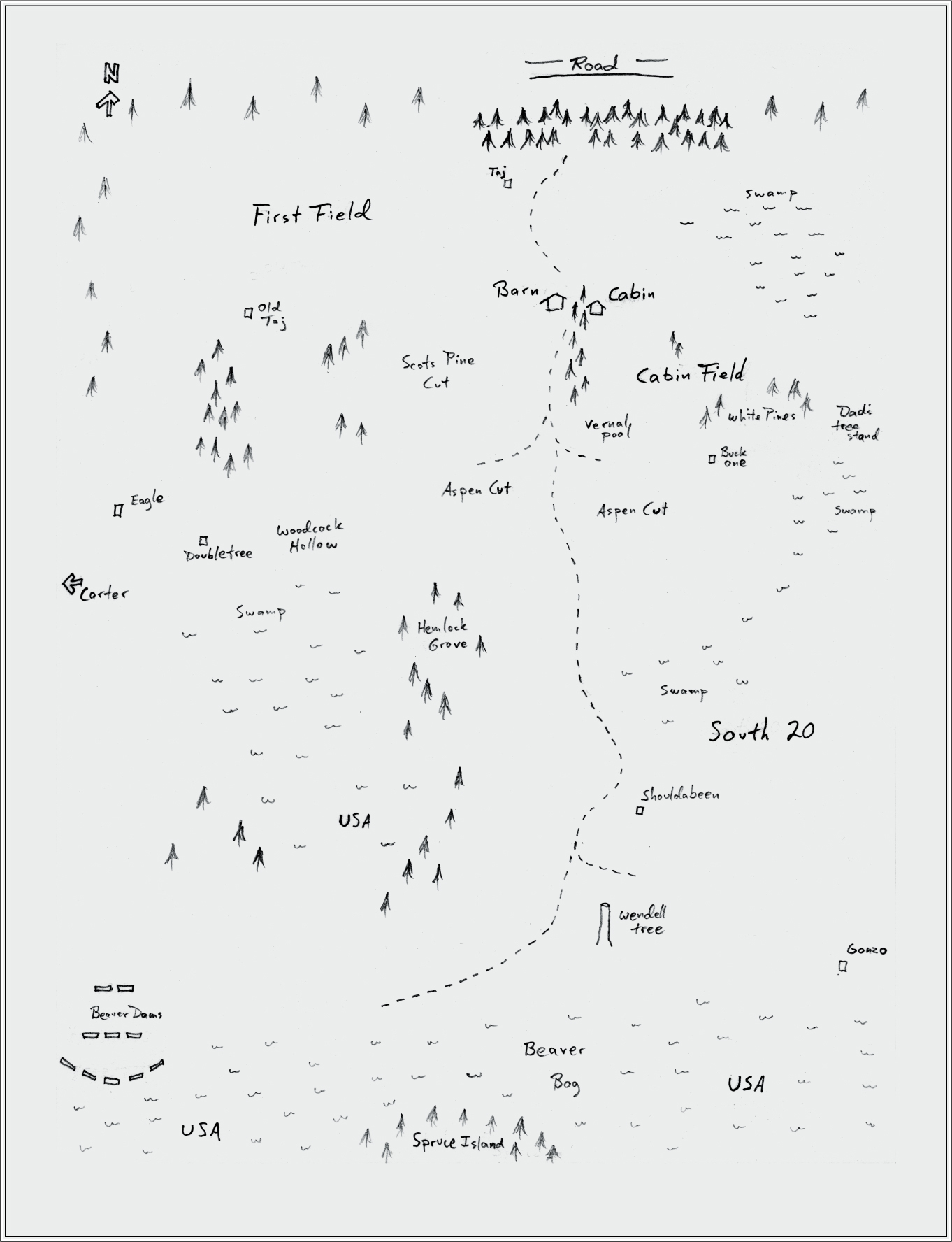

I go out. The night wind blows off Lake Michigan twenty miles to the west, smelling of algal water and sand and pines. Our camp is a worn-out farm halfway up Michigans Lower Peninsula, near the knee-deep meander of the North Fork of the White River, a spit of blow-sand left between the swamps when the Laurentide ice sheet retreated from this spot a little more than fourteen thousand years ago, the receding blade of the last ice age. All around us are swamp and other hunting properties, mostly former farms like ours that were beaned to death a century earlier and left in yellow, medium-coarse sand. Some are plantations of USDA red pine, some are third-growth mixed hardwood forest. Most are empty this time of year.

This night-sitting is a tactic that turned into a practice. When I was twelve years old, my father, Bruce, and I started hunting at a camp owned by a steel contractor named Bernard Cardheavy emphasis on the first syllable, BURN-erd and Mr. Card built deer blinds out of sheet metal and wood that were five-foot-by-five-foot boxes with a roof and an eighteen-inch gap in the walls all the way around, just right for sitting in a chair and watching deer.

Dad was a legendary still-hunter, and wed always settle in at least an hour before dawn and sit in total silence, a couple of times in cold so fierce I got frostbite on my jaw and earlobes waiting for sunrise. After the sun was up, we could use the propane heater without throwing light that would spook the wildlife. But that wasnt the relief I needed. I stopped wanting the sun to come up.

Sunup meant the hunt was on, and wed sit wordlessly for ten or eleven hours until the air in front of my face went dark again. I got to sit with my dad, but what I really needed was to talk to him. There werent many other opportunities. I wanted to talk to him about Mom, about my role in a house where he didnt live anymore, who I should be as the oldest son. Wed sit all day, my ass aching, and after it was too dark to shoot wed scuff down the frozen two-track toward dinner and talk in low voices about the deer and turkeys and owls wed seen, how many, the patterns in their movements. But thats all wed talk about. Dad was so exhausted from the intensity of his watching, practically conjuring whitetails by sheer force of will, that hed skip all the after-dinner whiskey and dirty jokes that were standard at Bernards and go straight to bed.