The society we have described can never grow into a reality or see the light of day, and there will be no end to the troubles of states, or indeed of humanity itself, till philosophers become kings in this world, or till those we now call kings and rulers really and truly become philosophers.

Plato, Republic 473cd

Philosophy begins in wonder.

Plato, Theaetetus 155d

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Bruno Leipold and Jonathan Wolff for help with Marx and Plato.

I was fortunate to be introduced to Plato by a number of superb teachers and scholars, to whom I am deeply indebted: Mary Margaret McCabe, Malcolm Schofield, David Sedley and Geoffrey Lloyd. Many thanks too to my fellow students Margaret Atkins and Dominic Scott, from whose work I have learned much and with whom I have enjoyed many years of enriching discussion of ancient philosophy.

My deepest thanks go to Myles Burnyeat, who supervised my PhD thesis on Platos Republic: inspirational teacher, writer and friend, and the embodiment of the very best kind of expertise.

Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2019

Text copyright Angie Hobbs, 2019

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Angelo Rinaldi

ISBN: 978-1-405-93384-1

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

The Publisher would like to thank the following for the illustrative references for this book:

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed, however if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

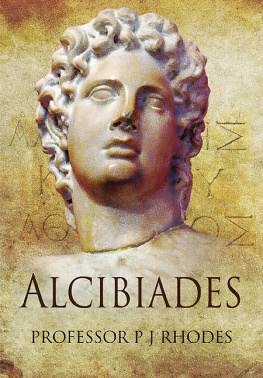

Angie Hobbs

PLATOS REPUBLIC

with illustrations by

Angelo Rinaldi

Platos world

Plato was born c. 428/427 BCE (possibly 424/423 BCE ) into an aristocratic Athenian family at a turbulent time: throughout his youth the city-state (polis) of Athens was engaged in a brutal civil war with the city-state of Sparta. Though they had come together to defeat the threat from the Persian Empire at the beginning of the century, after the Persians were overcome in 480 the two great Greek powers and their allies vied for supremacy; hostilities broke out in 431 and lasted until Athens was defeated in 404. Athens was also divided internally during this period between supporters of a democratic system of government in which all adult male citizens participated directly and those who favoured an oligarchic system in which power was in the hands of a wealthy few. Plato himself had family connections to both factions, and the desire to avoid internal strife shaped his political thinking.

As an aristocrat Plato was destined for a stellar political career. Two things changed his course. The first was his disgust with the violent extremes of the oligarchic faction, particularly when they briefly came to power in 404. Then, when democracy was restored in Athens, it put to death his beloved friend and mentor Socrates, purportedly for refusing to believe in the citys gods and introducing new ones, and for corrupting the young. In grief and revulsion Plato abandoned a conventional political career for a life in philosophy, the love of wisdom. After travels in Greece, southern Italy, Sicily and perhaps Cyrene and Egypt, in the 380s he set up a research and teaching institute, the Academy, just outside the Athenian city walls. Apart from two more trips to Sicily, he remained at the Academy for the rest of his life.

Platos work

Platos range is vast. He writes about ethics, political theory, psychology, aesthetics, knowledge and reality, and shows how he believes all these subjects interconnect. Probably inspired by Socrates oral style, he almost always chooses to write in dialogue form: deploying a wide and vivid cast of characters, he never writes in his own voice, thus encouraging his readers to enter into the debate and engage in active interpretation for themselves. Although Socrates is usually the main character, we cannot assume that Plato uncritically endorses everything he puts into Socrates mouth and Socrates words are often challenged by highly intelligent interlocutors, as they are in the Republic; nor can we assume that Socrates is the mouthpiece for the historical Socrates. With wit, verve and often detailed scene-setting, these dazzling works draw us into their richly imagined worlds.

The dialogue later called Res Publica by the Romans (Politeia in Greek) was probably written during the 370s, initially on wax tablets (there is a story that Plato experimented with many different versions of the opening sentence). It attracted immediate interest and papyrus copies were soon circulating freely around Athens; in the following century it appeared in the great library at Alexandria. It remained known usually through references in Latin by authors such as Cicero throughout the later classical world and the Middle Ages, and its readership expanded hugely in the fifteenth century when it was translated into Latin by the Florentine philosopher Marsilio Ficino. Its enduring appeal is explained in large part by its fundamental central questions: what is justice, and does it pay me personally to be just?

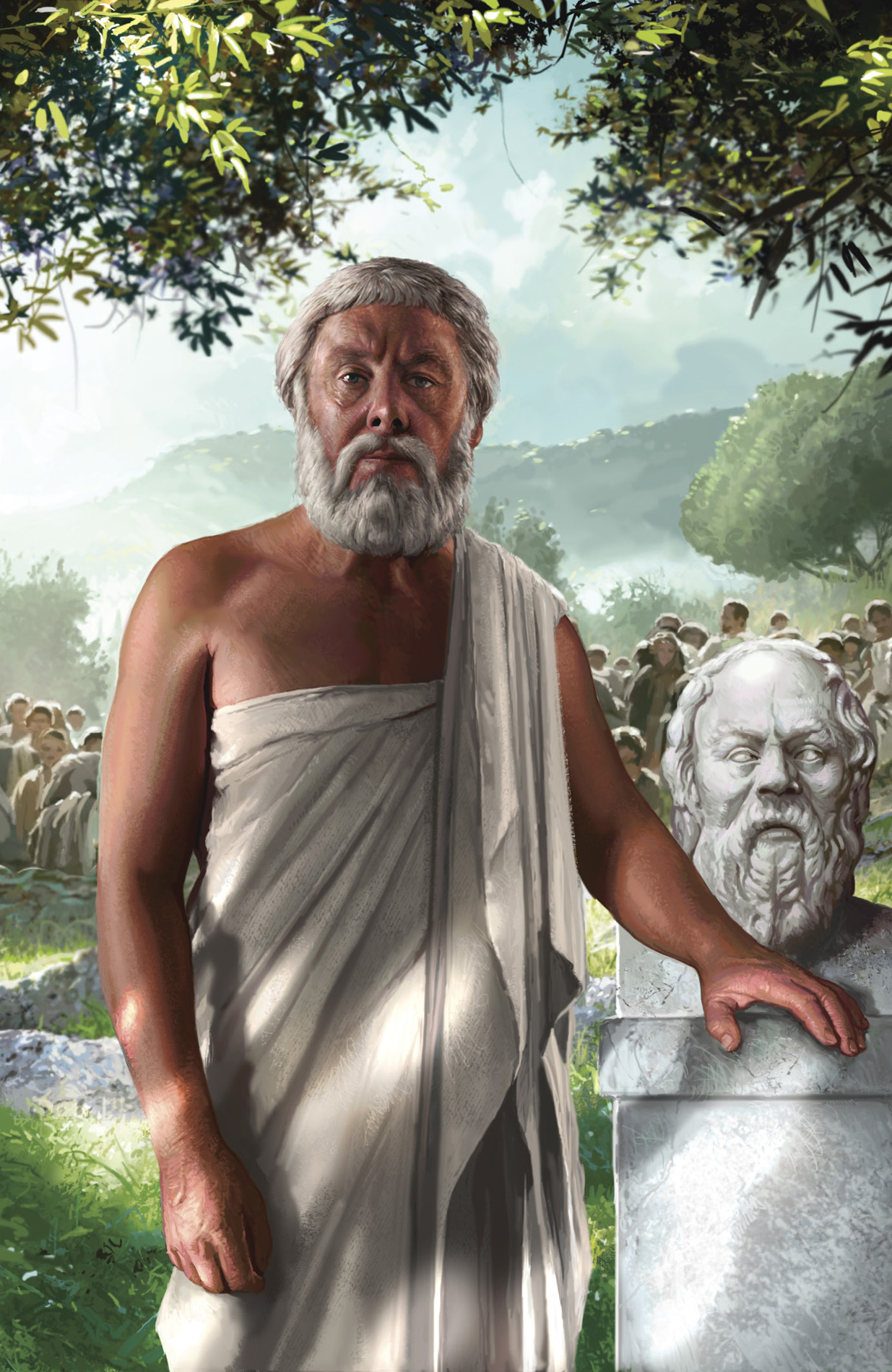

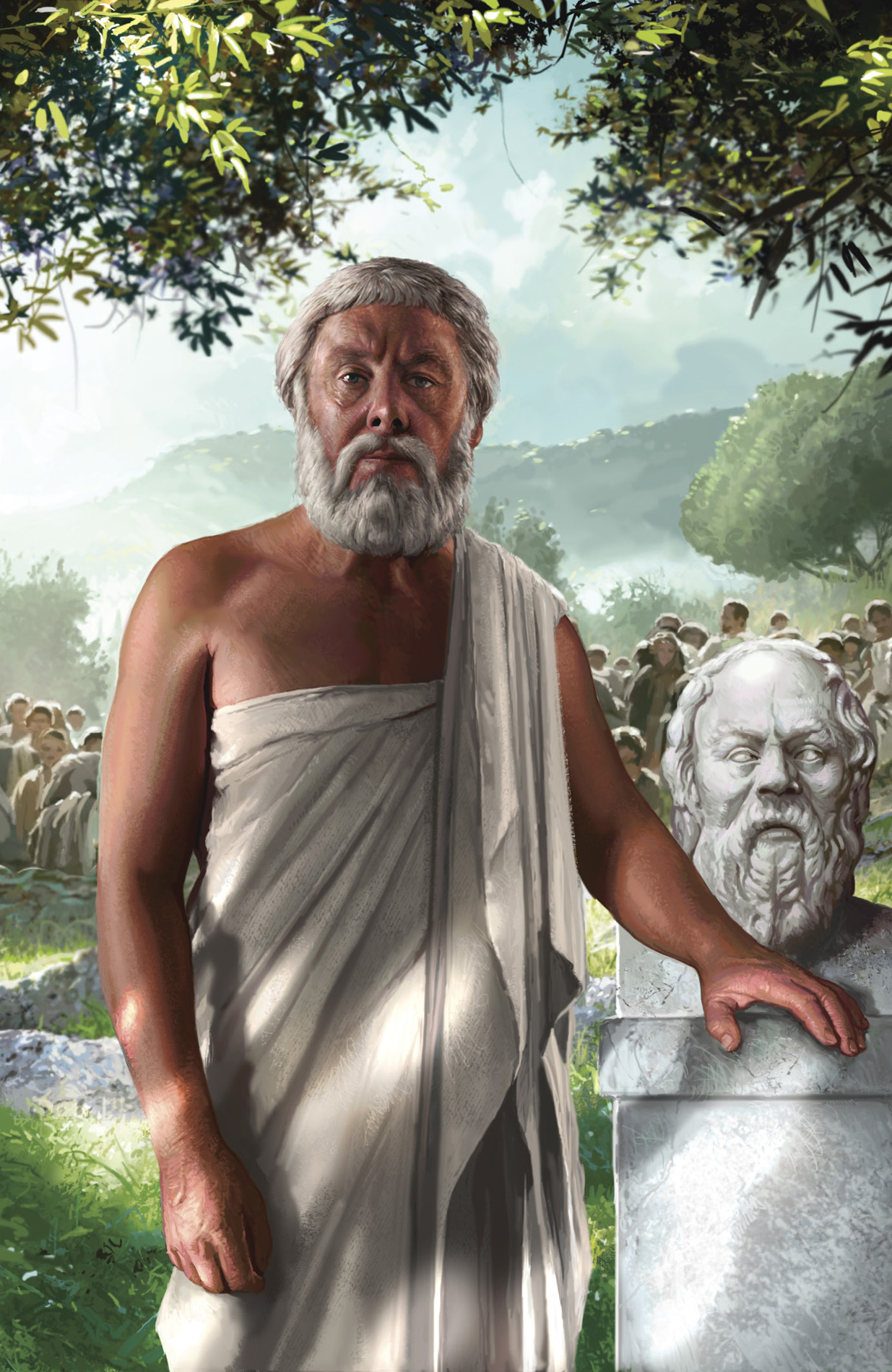

Plato standing by a bust of Socrates.

Layout of the Republic , and opening scene

Since at least the second century CE the Republic has traditionally been divided into ten books (although it is not clear that these divisions were made by Plato, who may have favoured six). Also in universal use is the referencing system to particular passages (such as 473c) derived from the sixteenth-century edition of the complete works of Plato by a French scholar known as Stephanus.

Next page

Plato standing by a bust of Socrates.

Plato standing by a bust of Socrates.