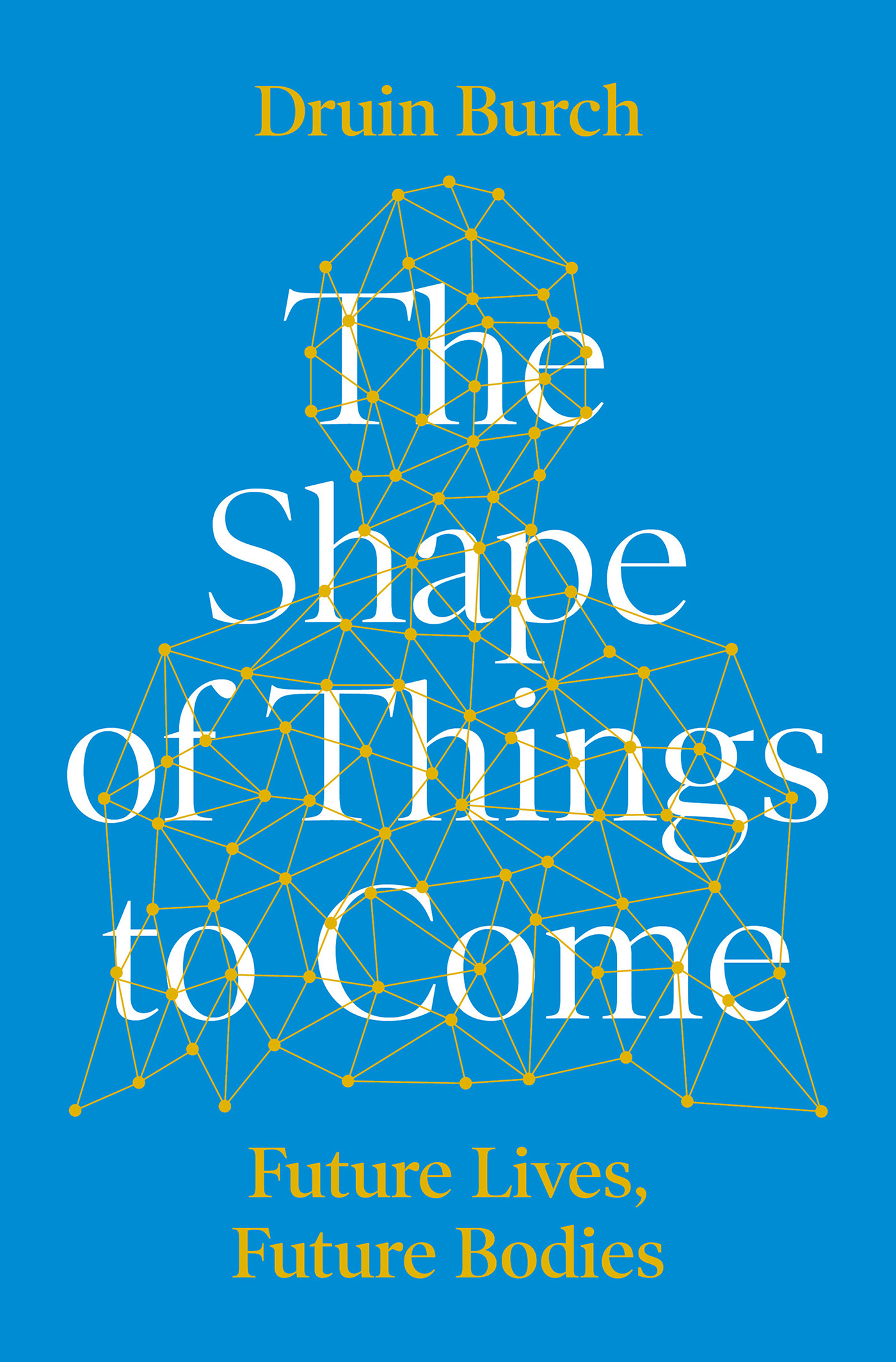

THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

Druin Burch

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2019 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright Druin Burch, 2019

The moral right of Druin Burch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781788543385

ISBN (E): 9781788543378

Cover design: Luke Bird

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

To Rachel Eleanor Burch,

whose spring helps make my summer

Contents

Speculating on what changes lie ahead for human lives, and human bodies, is relatively new. Science fiction has been fondly enthusiastic, as likely to attach tentacles as facts. But the serious exercise of imagination has not been possible for long, and not solely because we lacked the power to change very much. Before the late 1700s even the concept of change was unavailable. In a few dizzying decades at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, everything altered. You cannot look to the future without a feel for the past, and during those decades we first properly acquired it. Before that our knowledge told us our world had been largely unchanged in the 6,000 years since Creation. Explore the Holy Land and you would find that the Bible spoke accurately of its geography. Dig up mummified people and animals from beneath great pyramids and it was plain they were our fellow creatures. The only difference that was palpable was that the spirit of the age could always be compared unfavourably against that which was fading but that impulse, too, showed its own constancy over the years. What times, what manners, complained Cicero in 63 BC . My dear old friend, you and I shall never see such days again! The peaches are not so big now as they were, wrote the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon to Wordsworth in 1842. Happiness, said Spike Milligan, more than a hundred years later, is a yesterday thing.

Only slightly more than two centuries ago did we become able to see further back. Humans had not always been around, it turned out, nor mountains, nor seas, nor earth. Geologists, realising how old and strange the world was, complained of being deafened by the terrifying drip, drip, drip of time. Everything is in flux, Heraclitus had said, but he hadnt realised quite how true that was. A gentle meandering trickle had slowly carved out valleys and mountains and epochs. Tennyson wrote in melancholy amazement of nature as being too huge to treasure us. Gone was the sense of life on a scale such that not a sparrow fell without notice. Tennyson called nature indifferent to individuals and caring only to preserve species but even species, as lifes record became more readable, were expendable, even legions of them.

Astronomers wrote of looking to the heavens and feeling vertigo, their sense of self spinning out into the chilling hugeness. The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away. Thus spoke the psalm, confident and precise. As the vast stretch of the world swam into view, framed by what came to be called Deep Time and Deep Space, the Bible ceased to seem an easy and obvious guide to non-spiritual knowledge. Medicine became excitingly unmoored the assumption that the Greeks and Romans had known all there was to know, that it was the job of modern practitioners solely to guard and preserve their wisdom, evaporated into the cold gap between the stars, split apart with the relentless tapping of the geologists hammer. When the past turned out to have been so unfathomably strange, what might the future bring? Who knew now what was possible? While he was developing vaccination, Edward Jenner wrote excitedly to John Hunter, asking his old mentor whether he thought an idea would work. Why think? Hunter replied scornfully, why not try the experiment? Our physiques, our lifespans and our vitality were no longer set in the stone frame of constancy. In them, as in all else, lay a boundless potential for experiment, change and discovery. The past no longer belonged to us. As a consequence, the future did. The sense that its form was not fixed meant it was ours to mould.

*

Life reshapes itself. Plants take in carbon dioxide but breathe out oxygen. Their expirations allowed the inspiration giving life to a million others. Many creatures became enrolled, usually to mutual benefit, as sex aids to the plants. Reshaping goes on within species too. An old joke has two weary fellows bathing their feet in an African stream. They see a group of hungry lions approach, and one man dries his feet and starts putting on his socks and his shoes. Whats the point? asks the other, we cant outrun lions. True, the first replies, with a touch of manly regret, but I can outrun you. Competition fuels survival, and survival is the engine of change. As the biologist J. B. S. Haldane pointed out, even the origins of altruism can be explained by genetic self-interest he would sacrifice himself, he said, to save eight first cousins or two brothers. It was Darwin who noticed that natural selection did not merely pick out traits of direct advantage but did other, subtler things too. Stephen Jay Gould, late in the twentieth century, described some as ineluctable consequences of structural design. Male humans, like male lions, became faster and stronger and larger than their female counterparts because males compete by fighting with each other. Women with a taste for pace, strength and size in their men were more likely to have successful offspring. Qualities that began as practical became aesthetic. The same applies outside the limited boundaries of physicality. Truth and honour emerge as characteristics that aid survival and reproductive success, but they win their place in our genes by winning a place in our hearts. Our sense of morality and beauty is not a false overlay on our real desires but the structure that supports them. I could not love thee, dear, so much, / Loved I not honour more has a spine of truth.

Sexual taste, not solely for an isolated physical act but for a relationship and a shared family life, literally blends everything together. Within an alpha male system, where males fight to the death and females take the winner, males are larger in order to give themselves the outside chance of bloody success. But the pressures remain when the race is no longer to the swiftest, nor the battle to the strong. To live is to choose. Selecting on the basis of wit, honeyed voice, sound judgement or upright morality is still to select. Your choices shape the future just as, over generations, tastes shape success, and success shapes taste. It says something about different human cultures and shared evolution that one can no longer become American president without being tall; it says something else that this is not so vital for a British prime minister. Linking specifics too glibly to evolution is hazardous, a guarantee of superficiality, but some relationship exists, however indirect and hard to trace. We strive to suit our own tastes and those of others. When you see a wildflower you see a bees sense of beauty. We develop to match the tastes of those we seek to please, to make hungry where most we satisfy. There is a reason peacocks and birds of paradise come easily to mind when contemplating human preening. Beauty might be skin deep but similarities are not.