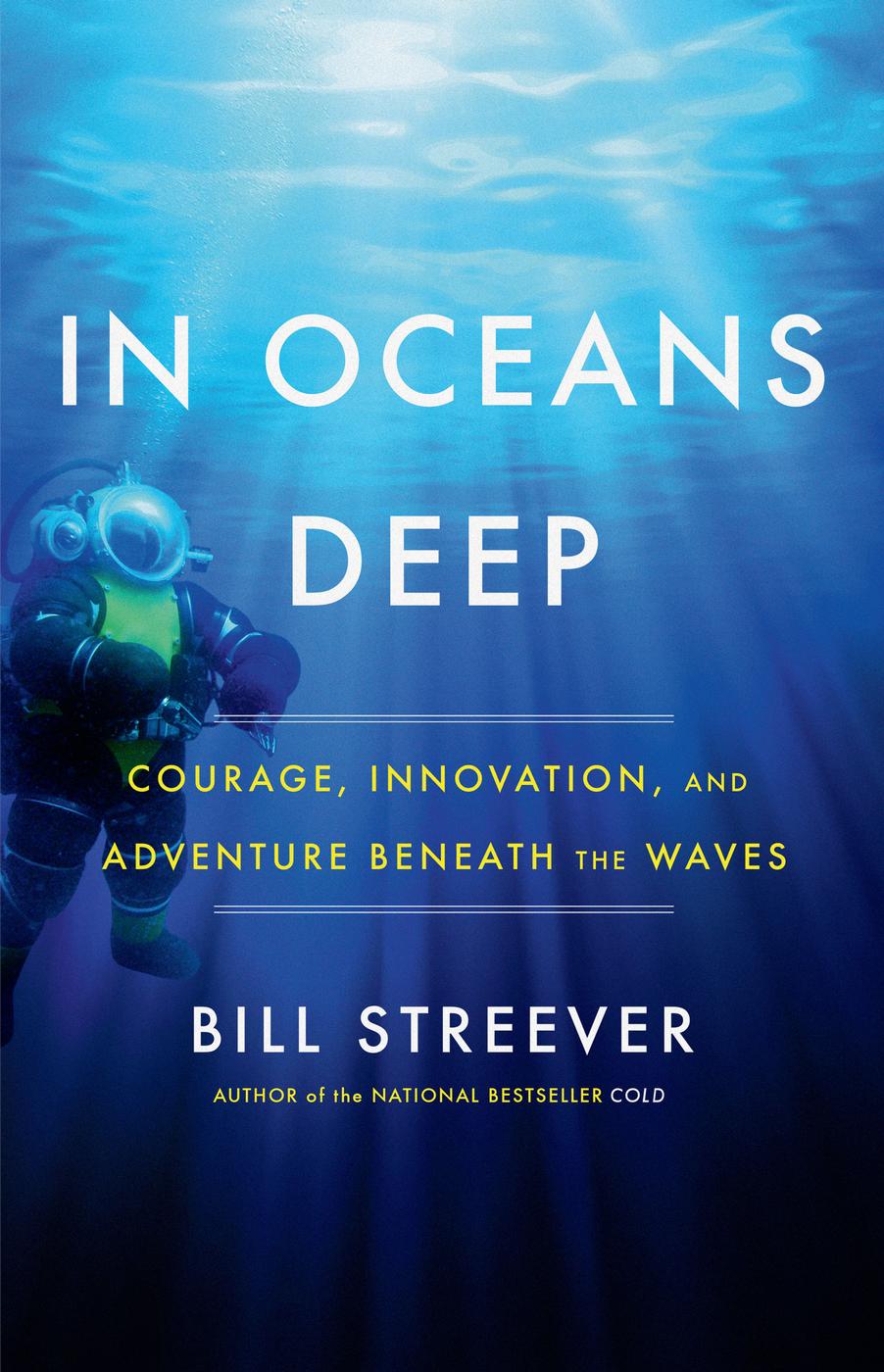

Copyright 2019 by Bill Streever

Cover design by Gregg Kulick

Cover art by Mondadori Portfolio / Getty (diver), Magnilion / Getty (underwater)

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Author photograph by Lisanne Aerts

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

facebook.com/LittleBrownandCompany

twitter.com/LittleBrown

First ebook edition: July 2019

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are within the public domain.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-55135-9

LCCN 2018965114

E3-20190530-DA-NF-ORI

For my late father, who always supported my love of the world beneath the waves.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

O abyss! O eternal Godhead! O deep sea! What more could you have given me than the gift of your very self?

Saint Catherine of Siena

So my message is, in whichever realm, be it going into space or going into the deep sea, you have to balance the yin and yang of caution and boldness, risk aversion and risk taking, fear and fearlessness.

James Cameron, Titanic and Other Reflections, 2004

Every person on this earth depends on the sea in some way. My gosh, if only we could get folks interested in that part of our planet, the benefits could be unlimited. But first, someone has to notice.

Bob Barth, U.S. Navy Sealab diver, 2000

This book is not a diving manual. Safe diving in all of its many forms requires training provided by internationally recognized organizations. Nothing in this volume should be construed as encouraging anyone to ignore widely accepted standards for education, equipment, depth limitations, experience, and other factors that minimize risks.

M y father, who was my first diving partner well before I was old enough to drive, built his working life around running midsize businesses. But when I was barely out of high school and found my first job diving, he was more than supportive. He was enthusiastic. On several occasions, I overheard him bragging to friends and colleagues about his son the oil field diver, the kid making his living underwater with explosives and cutting torches, the young man assembling pipelines on the seabed.

Ten years later, when I walked away from a successful run as a diver to pursue a university degree, he was disappointed. This was a legitimate reaction. My work had taken me from the Gulf of Mexico to the South China Sea. It had provided an opportunity to dive while breathing exotic gases and to live at depth with three colleagues for monthlong stretches. My future looked far less exciting. And to this day, it seems at times that one of my biggest mistakes was turning my back on a career underwater.

On the other hand, I had suffered several diving injuries and survived a few close encounters with my own mortality. I had grown tired of the time I was spending at sea, as much as eight months during busy years. During quieter periods, the uncertainty of living from contract to contract and weathering lean seasons without a paycheck took its toll. And there were two supervisors I respected who quietly encouraged me to get out of the business while I was still young, to pursue an education, something that had eluded both of them despite their abundant intelligence and talent.

And so I went to college. I became a biologist and a writer. I ran research programs in Australia and Alaska. I continued to lead a reasonably interesting life. But it could never compete with what had come before. So whenever possible, I inserted myself into field studies that required diving or the use of underwater sampling gear, things such as dredges, grab samplers, nets, and even hydrophones that recorded the vocalizations of passing whales and the noises from ships. And I dived recreationally, usually with scuba gear, whenever and wherever I could. Diving remained, and will continue to be, an important part of my day-to-day existence.

Back to my father. When my book Cold was reviewed in his favorite magazine, the Economist, he urged me to write something about diving. Later, as Parkinsons disease ravaged first his body and then his mind, he grew adamant.

I told him there were problems with such a book. Many great works had already covered the topic, but few had found a wide readership. And there was the question of whether my style of writing suited the subject. Most of what I had read on underwater exploration tended toward either personal exploits or something close to a textbook, but as an author I was partial to narratives shaped by science and history.

After several years of reflection, I realized that what I had to write could not be limited to diving in the conventional sense but instead would tackle what I came to think of as humanitys presence beneath the waves. When friends asked about my work, I would repeat those exact words. And then I would explain myself, adding something like, You know, diving, submarines, submersibles, and underwater robots.

Even then, I had to consider how to capture the essence of my subject while also captivating readers. I had to figure out how to do justice to this amazing story. Well into the first year of research and interviews for what became In Oceans Deep, my approach remained undetermined, until one day, while I was free diving, something close to inspiration struck. Afterward, of course, the book continued to evolve, and very late in the process it went through a major change following an interview with the worlds most famous female diver and underwater conservationist, Dr. Sylvia Earle.

I never intended to write an unabridged treatise on humanitys presence underwater. I meant instead to create the kind of book that would leave a lasting impression. I wanted readers to finish the last page with a newfound or rejuvenated motivation to free dive, to scuba dive, to consider passage in any one of the increasingly common tourist submersibles capable of reaching beyond one thousand feet, to watch undersea documentaries, to consider buying an underwater robot of their own, and to talk to marine scientists and submariners and the engineers whose work lies beneath the surface of the sea. In other words, I wanted readers to embrace the part of our world that is shrouded by depth.

I continue to hope that In Oceans Deep will bring attention to one of the most important yet under-discussed topics of our time. Past accomplishments and the feats being attempted today are barely known to the general public. Even among those who work underwater, knowledge is far too compartmentalized. For example, champion free divers may know nothing about submersibles, and submersible pilots might know very little about the strange gas mixtures that allow divers to breathe below one thousand feet. And the link between the ways in which humans access the underwater world and the struggle to protect our troubled oceans deserves far more consideration than it receives.