O n a table in my suburban Anchorage home: a stubby red candle, matches, an electronic thermometer, a bowl of snow, and my ungloved left hand.

I look at the palm of my left hand: for now unburned, soft and uncalloused, scarred from a long-ago accident with a knife. On the back of my hand: fine blond hairs and early wrinkles of aging skin.

I strike a match, hold it while the flame stabilizes, and touch it to the candles wick.

I move the back of my hand through the flame and smell melting hair. Hair is keratin, the same stuff in feathers and hooves and fingernails and baleen, a complicated protein, its long molecules coiled and folded upon themselves. The smell is that of protein molecules uncoiling and unfolding, coming unglued, losing their three-dimensional structure, denaturing.

Firefighters sometimes talk of skin melting. A Chicago firefighter struggled to carry a woman from a burning house. She was slipping out of my hands because my skin was melting, he later told an interviewer. On my left hand, the melted skin had fused together my fingers.

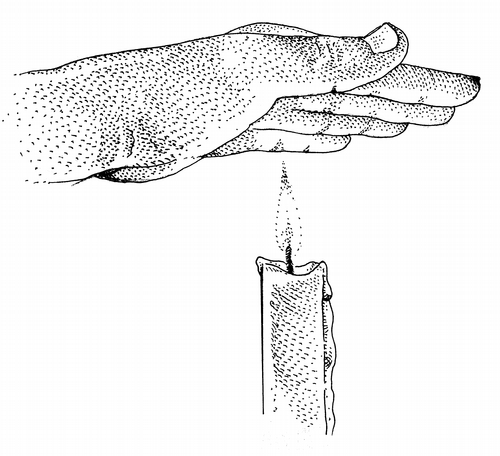

I pass my palm quickly through the flame. I feel a mild sensation of heat. One of the lessons of heat: duration of contact matters.

From Herman Melvilles Mr. Stubb, lover of rare meat and second mate aboard the Pequod during her pursuit of Moby Dick, on how to cook a whale steak: Hold the steak in one hand, and show a live coal to it with the other.

Two centuries before Melville, scientists tried to understand heat. The German scientists Johann Joachim Becher and Georg Ernst Stahl promoted the phlogiston theory. Flammable materials contained phlogiston, a colorless substance with neither taste nor odor. Burning removed phlogiston. A burning candle became dephlogisticated. A steak held to a live coal long enough could become dephlogisticated. My hand, held in the flame long enough, could become dephlogisticated.

A century later, the great French scientist Antoine Lavoisier, the man who named oxygen and hydrogen, dephlogisticated the phlogiston theory. He argued that heat was a subtle fluid. He called the fluid caloric.

Antoine Lavoisier was as wrong as Becher and Stahl.

Slowly, I move my hand, palm down, toward the flame. At a distance of six inches above the flame, the heat becomes uncomfortable. It becomes a threat. I pull back.

During Melvilles lifetime, Michael Faraday played with candles. Faraday is best known for his experiments and discoveries in magnetism and electricity, but he cherished the burning candle as a lecture topic. In 1860 he published his lectures as The Chemical History of a Candle.

There is no more open door by which you can enter into the study of natural philosophy, Faraday wrote, than by considering the physical phenomena of a candle.

With my electronic thermometer, I measure my candles flame. It is an infrared thermometer, a pyrometer, capable of measuring heat from a distance, capable of seeing heat as the eye sees light. It looks beyond the visible spectrum, seeing wavelengths longer than the reddest of reds. The thermometer has the shape of a toy pistol, a gray phaser with a yellow trigger. Heat waves enter through the barrel, pass through a lens, and are focused on a thermopile. The thermopile converts heat waves to electricity. Circuitry converts the electricity into a digital readout. The digital readout says 1,350 degrees.

Faraday, in his candle lectures, described the candle flame as a hollow shell. Inside the shell there is no oxygen and therefore no fire.

I attach a steel-tipped probe to my thermometer, bypassing its optics. I push the probe into the unburning core for a reading of 1,200 degrees. At the tip of the flame, where oxygen meets hot gas, where ignition creates a yellow flare, I read 1,360 degrees, only 10 degrees off from the infrared reading. This is where I plan to bathe my hand, a five-second intentional exposure.

Twenty-three years after the publication of Moby Dick and seven years after Faraday died, Harry Houdini was born. Houdini grew up to become a Vaudeville star, an escape artist and illusionist, a film director, a skeptic, an exposer of lesser magicians, and a theatrical pyromaniac. Among his many offerings: instructions for cooking a steak. Houdinis instructions involved something more than a hot coal. To cook a steak, he required a cage. The cage should be made of iron, with dimensions of four feet by six feet. Its bars should be wrapped in oil-soaked cotton.

Now take a raw beefsteak in your hand and enter the cage, Houdini wrote.

A stagehand ignites the oil-soaked cotton wrapped around the bars. Smoke and flames hide the performer from the audience. Inside, the performer hangs the steak from a hook above his head and then lies facedown on the bottom of the cage. The performers cloak, including a hood, is made from asbestos fabric. The performer breathes through a hole in the bottom of the cage. The heat rises and cooks the steak.

Remain in the cage until the fire has burned out, Houdini instructed, then issue from the cage with the steak burned to a crisp.

I stare at the candles brilliant yellow, its flickering blue, the molten wax at its base. From a society that promotes meditation: Relax your body and mind as much as you can, and watch the candle flame. Do not strain your eyes while focusing on the candle flame, as the focusing you will be doing is in your mind, not in your eyes. Clear all of your thoughts, and focus them only on the flame.

Looking into the flame, I cannot clear my thoughts. I think of Faraday. He mentioned the sperm candle, which comes from the purified oil of the spermaceti whale. During lectures, he ignited alcohol, phosphorous, zinc, hydrogen, a reed soaked in camphene, and the spores from club moss. He burned everything in reach.

John Tyndall was a friend and admirer of Faraday, a user of a primitive thermopile, and Faradays successor as director of the Royal Institution. Tyndall was intimately familiar with Faradays candle lectures. He discovered that carbon dioxide can trap heat in the atmosphere. And he knew that heat was not a substance. It was not a fluid, subtle or otherwise. It was an expression of molecular motion.